Artificial Intelligence beats us in chess, but not in memory

The brain strategy for storing memories is more efficient than AI's one, a new study reveals

2021-01-15

(Press-News.org) In the last decades, Artificial Intelligence has shown to be very good at achieving exceptional goals in several fields. Chess is one of them: in 1996, for the first time, the computer Deep Blue beat a human player, chess champion Garry Kasparov. A new piece of research shows now that the brain strategy for storing memories may lead to imperfect memories, but in turn, allows it to store more memories, and with less hassle than AI. The new study, carried out by SISSA scientists in collaboration with Kavli Institute for Systems Neuroscience & Centre for Neural Computation, Trondheim, Norway, has just been published in Physical Review Letters.

Neural networks, real or artificial, learn by tweaking the connections between neurons. Making them stronger or weaker, some neurons become more active, some less, until a pattern of activity emerges. This pattern is what we call "a memory". The AI strategy is to use complex long algorithms, which iteratively tune and optimize the connections. The brain does it much simpler: each connection between neurons changes just based on how active the two neurons are at the same time. When compared to the AI algorithm, this had long been thought to permit the storage of fewer memories. But, in terms of memory capacity and retrieval, this wisdom is largely based on analysing networks assuming a fundamental simplification: that neurons can be considered as binary units.

The new research, however, shows otherwise: the fewer number of memories stored using the brain strategy depends on such unrealistic assumption. When the simple strategy used by the brain to change the connections is combined with biologically plausible models for single neurons response, that strategy performs as well as, or even better, than AI algorithms. How could this be the case? Paradoxically, the answer is in introducing errors: when a memory is effectively retrieved this can be identical to the original input-to-be-memorized or correlated to it. The brain strategy leads to the retrieval of memories which are not identical to the original input, silencing the activity of those neurons that are only barely active in each pattern. Those silenced neurons, indeed, do not play a crucial role in distinguishing among the different memories stored within a same network. By ignoring them, neural resources can be focused on those neurons that do matter in an input-to-be-memorized and enable a higher capacity.

Overall, this research highlights how biologically plausible self-organized learning procedures can be just as efficient as slow and neurally implausible training algorithms.

INFORMATION:

[Attachments] See images for this press release:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-01-15

An innovative new study is set to examine if changing our mealtimes to earlier or later in the day could reduce the risk of developing Type 2 diabetes.

Led by Dr Denise Robertson, Professor Jonathan Johnston and post graduate researcher Shantel Lynch from the University of Surrey, the study, outlined in the journal Nutrition Bulletin, will investigate if changing the time we eat during the day could reduce risk factors such as obesity and cholesterol levels that are typically associated with the development of Type 2 diabetes. The team of researchers will also for the first time investigate, via a series of interviews with participants and their friends and family, the impact of such changes on home life, work/social commitments and whether co-habitants of those who make such ...

2021-01-15

Having genitals of a certain shape and size gives male flies a major reproductive advantage, new research shows.

University of Exeter scientists examined the reproductive success of male Drosophila simulans flies both alone with a female and in various states of competition with other males.

Certain genital shapes were consistently better in terms of number of offspring sired.

However - surprisingly, given how fast genital form evolves - the selection documented was rather weak.

"Male genitals generally, and in Drosophila specifically, evolve very quickly, so we were really surprised to find this weak selection," said Professor David Hosken, of the University of Exeter.

"Selection is the major mechanism of evolution and hence where we see rapid evolution, ...

2021-01-15

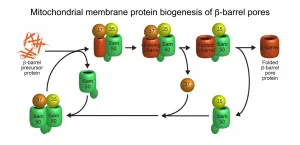

Mitochondria are vital for the human body as cellular powerhouses: They possess more than 1,000 different proteins, required for many central metabolic pathways. Disfunction of these lead to severe diseases, especially of the nervous system and the heart. In order to transport proteins and metabolites, mitochondria contain a special group of so-called beta-barrel membrane proteins, which form transport pores in the outer mitochondrial membrane. So far, scientists have not been able to explain the operating mode of the sorting and assembly machinery (SAM) for the biogenesis of these beta-barrel proteins. A team led by Prof. Dr. Toshiya Endo from Kyoto University/Japan, Prof. Dr. Nils Wiedemann and ...

2021-01-15

Guangzhou, January 15, 2021: New journal BIO Integration (BIOI) publishes its fourth issue, volume 1, issue 4. BIOI is a peer-reviewed, open access, international journal, which is dedicated to spreading multidisciplinary views driving the advancement of modern medicine. Aimed at bridging the gap between the laboratory, clinic, and biotechnology industries, it will offer a cross-disciplinary platform devoted to communicating advances in the biomedical research field and offering insights into different areas of life science, in order to encourage cooperation and exchange among scientists, clinical researchers, and health care providers.

The issue contains an original article, three review ...

2021-01-15

A clinical trial involving COVID-19 patients hospitalized at UT Health San Antonio and University Health, among roughly 100 sites globally, found that a combination of the drugs baricitinib and remdesivir reduced time to recovery, according to results published Dec. 11 in the New England Journal of Medicine. Six researchers from UT Health San Antonio and University Health are coauthors of the publication because of the San Antonio site's sizable patient enrollment in the trial.

The Adaptive COVID-19 Treatment Trial 2 (ACTT-2), which compared the combination therapy versus remdesivir paired with an inactive placebo in hospitalized COVID-19 patients, was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), ...

2021-01-15

Certain snakes have evolved a unique genetic trick to avoid being eaten by venomous snakes, according to University of Queensland research.

Associate Professor Bryan Fry from UQ's Toxin Evolution Lab said the technique worked in a manner similar to the way two sides of a magnet repel each other.

"The target of snake venom neurotoxins is a strongly negatively charged nerve receptor," Dr Fry said.

"This has caused neurotoxins to evolve with positively charged surfaces, thereby guiding them to the neurological target to produce paralysis.

"But some snakes have evolved to replace a negatively charged amino acid on their receptor with a positively charged one, meaning the neurotoxin is repelled.

"It's an inventive genetic mutation and it's been completely missed until now.

"We've ...

2021-01-15

PHILADELPHIA - Our biological or circadian clock synchronizes all our bodily processes to the natural rhythms of light and dark. It's no wonder then that disrupting the clock can wreak havoc on our body. In fact, studies have shown that when circadian rhythms are disturbed through sleep deprivation, jet lag, or shift work, there is an increased incidence of some cancers including prostate cancer, which is the second leading cause of cancer death for men in the U.S. With an urgent need to develop novel therapeutic targets for prostate cancer, researchers at the Sidney Kimmel Cancer - ...

2021-01-15

Oxygen levels in the ancient oceans were surprisingly resilient to climate change, new research suggests.

Scientists used geological samples to estimate ocean oxygen during a period of global warming 56 million years ago - and found "limited expansion" of seafloor anoxia (absence of oxygen).

Global warming - both past and present - depletes ocean oxygen, but the new study suggests warming of 5°C in the Paleocene Eocene Thermal Maximum (PETM) led to anoxia covering no more than 2% of the global seafloor.

However, conditions are different today to the PETM - today's rate of carbon emissions is much faster, and we are adding nutrient pollution to the oceans - both of which could drive more rapid and expansive oxygen loss.

The study was carried out by an international ...

2021-01-15

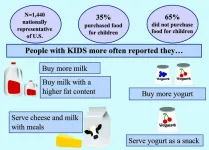

Champaign, IL, January 15, 2021 - American dairy consumers are often influenced by a variety of factors that can affect their buying habits. These factors include taste, preference, government information, cultural background, social media, and the news. In an article appearing in JDS Communications, researchers found that households that frequently bought food for children are interested in dairy as part of their diet and purchased larger quantities of fluid milk and more fluid milk with a higher fat content.

To assess the purchasing habits of households that purchase food for children versus those ...

2021-01-15

Families are complicated. For members of the Alligatoridae family, which includes living caimans and alligators - this is especially true. They are closely related, but because of their similarity, their identification can even stump paleontologists.

But after the recent discovery of a partial skull, the caimans of years past may provide some clarity into the complex, and incomplete, history of its relatives and their movements across time and space.

Michelle Stocker, an assistant professor of vertebrate paleontology in Virginia Tech's Department of Geosciences in the College of Science; Chris Kirk, of the University of Texas at Austin; and Christopher Brochu, of the University of Iowa, have ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Artificial Intelligence beats us in chess, but not in memory

The brain strategy for storing memories is more efficient than AI's one, a new study reveals