(Press-News.org) Like a person breaking up a cat fight, the role of catalysts in a chemical reaction is to hurry up the process - and come out of it intact. And, just as not every house in a neighborhood has someone willing to intervene in such a battle, not every part of a catalyst participates in the reaction. But what if one could convince the unengaged parts of a catalyst to get involved? Chemical reactions could occur faster or more efficiently.

Stanford University material scientists led by Jennifer Dionne have done just that by using light and advanced fabrication and characterization techniques to endow catalysts with new abilities.

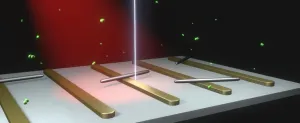

In a proof-of-concept experiment, rods of palladium that were approximately 1/200th the width of a human hair served as catalysts. The researchers placed these nanorods above gold nanobars that focused and "sculpted" the light around the catalyst. This sculpted light changed the regions on the nanorods where chemical reactions - which release hydrogen - took place. This work, published Jan. 14 in Science, could be an early step toward more efficient catalysts, new forms of catalytic transformations and potentially even catalysts capable of sustaining more than one reaction at once.

"This research is an important step in realizing catalysts that are optimized from the atomic-scale to the reactor-scale," said Dionne, associate professor of materials science and engineering who is senior author of the paper. "The aim is to understand how, with the appropriate shape and composition, we can maximize the reactive area of the catalyst and control which reactions are occurring."

A mini lab

Simply being able to observe this reaction required an exceptional microscope, capable of imaging an active chemical process on an extremely small scale. "It's difficult to observe how catalysts change under reaction conditions because the nanoparticles are extremely small," said Katherine Sytwu, a former graduate student in the Dionne lab and lead author of the paper. "The atomic-scale features of a catalyst generally dictate where a transformation happens, and so it's crucial to distinguish what's happening within the small nanoparticle."

For this particular reaction - and the later experiments on controlling the catalyst - the microscope also had to be compatible with the introduction of gas and light into the sample.

To accomplish all of this, the researchers used an environmental transmission electron microscope at the Stanford Nano-Shared Facilities with a special attachment, previously developed by the Dionne lab, to introduce light. As their name suggests, transmission electron microscopes use electrons to image samples, which allows for a higher level of magnification than a classic optical microscope, and the environmental feature of this microscope means that gas can be added into what is otherwise an airless environment.

"You basically have a mini lab where you can do experiments and visualize what's happening at a near-atomic level," said Sytwu.

Under certain temperature and pressure conditions, hydrogen-rich palladium will release its hydrogen atoms. In order to see how light would affect this standard catalytic transformation, the researchers customized a gold nanobar - designed using equipment at the Stanford Nano-Shared Facilities and the Stanford Nanofabrication Facility - to sit below the palladium and act as an antenna, collecting the incoming light and funneling it to the nearby catalyst.

"First we needed to understand how these materials transform naturally. Then, we started to think about how we could modify and actually control how these nanoparticles change," said Sytwu.

Without light, the most reactive points of the dehydrogenation are the two tips of the nanorod. The reaction then travels through the nanorod, popping out hydrogen along the way. With light, however, the researchers were able to manipulate this reaction so that it traveled from the middle outward or from one tip to the other. Based on the location of the gold nanobar and the illumination conditions, the researchers managed to produce a variety of alternative hotspots.

Bond breaking and breakthroughs

This work is one of the rare instances showing that it is possible to tweak how catalysts behave even after they are made. It opens up significant potential for increasing efficiency at the single-catalyst level. A single catalyst could play the role of many, using light to perform several of the same reactions across its surface or potentially increase the number of sites for reactions. Light control may also help scientists avoid unwanted, extraneous reactions that sometimes occur alongside desired ones. Dionne's most aspirational goal is to someday develop efficient catalysts capable of breaking down plastic at a molecular level and transforming it back to its source material for recycling.

Dionne emphasized that this work, and whatever comes next, would not be possible without the shared facilities and resources available at Stanford. (These researchers also used the Stanford Research Computing Center to do their data analysis.) Most labs cannot afford to have this advanced equipment on their own, so sharing it increases access and expert support.

"What we can learn about the world and how we can enable the next big breakthrough is so critically enabled by shared research platforms," said Dionne, who is also senior associate vice provost for research platforms/shared facilities. "These spaces not only offer critical tools, but a really amazing community of researchers."

INFORMATION:

Additional Stanford co-authors include former postdoctoral scholar Michal Vadai, former doctoral student Fariah Hayee, and graduate students Daniel K. Angell, Alan Dai and Jefferson Dixon.

This research was funded by the SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory; the National Science Foundation, including the Alan T. Waterman award, the U.S. Department of Energy (partially as part of the "Photonics at Thermodynamic Limits" Energy Frontier Research Center), Office of Science, Division of Materials Science and Engineering, the Gabilan Stanford Graduate Fellowship, the TomKat Center for Sustainable Energy at Stanford, the Diversifying Academia, Recruiting Excellence (DARE) Doctoral Fellowship Program at Stanford. Dionne is also a courtesy faculty in Radiology, member of the Wu Tsai Neurosciences Institute and Stanford Bio-X, and an affiliate of the Precourt Institute for Energy.

COLUMBIA, Mo. - When he was in middle school, teachers would give Sam Curran a list of words to type in a computer to practice his vocabulary. But Sam, who has autism, was unable to stay focused on the task and required a significant amount of one-to-one direction from a teacher to complete his work. After his mother, Alicia, persuaded his teachers to allow Sam to change the colors of the words, he was able to complete work more independently and began making remarkable progress.

Now 20 years old, Sam's mother continues to ensure his special interests are leveraged in an effort to continue to help him grow and develop. A new survey from the MU Thompson Center for Autism and Neurodevelopmental Disorders has found that similar strategies for children with disabilities can help reduce anxiety ...

A new Northwestern University-led study is unfolding the mystery of how RNA molecules fold themselves to fit inside cells and perform specific functions. The findings could potentially break down a barrier to understanding and developing treatments for RNA-related diseases, including spinal muscular atrophy and perhaps even the novel coronavirus.

"RNA folding is a dynamic process that is fundamental for life," said Northwestern's Julius B. Lucks, who led the study. "RNA is a really important piece of diagnostic and therapeutic design. The more we know about RNA folding and complexities, the better we can design treatments."

Using data from RNA-folding experiments, the researchers generated the first-ever data-driven movies of how RNA folds as it is made by cellular ...

Nearly 38 million people around the world are living with HIV, which, with access to treatment, has become a lifelong chronic condition. Understanding how infection changes the brain, especially in the context of aging, is increasingly important for improving both treatment and quality of life.

In January, researchers at the Mark and Mary Stevens Neuroimaging and Informatics Institute (USC Stevens INI), part of the Keck School of Medicine of USC, and other international NeuroHIV researchers, published one of the largest-ever neuroimaging studies of HIV. The researchers pooled magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) data from 1,203 HIV-positive individuals across Africa, ...

The White-lipped peccary Tayassu pecari is a boar-like hoofed mammal found throughout Central and South America. These animals roam the forest in bands of 50 to 100 individuals, eating a wide variety of foods. In Brazil's Atlantic Rainforest, they prefer the fruit of the jussara palm Euterpe edulis.

The jussara is very abundant in this biome, probably thanks to vast amounts of dung, urine, and soil trampling by peccaries as well as tapirs (Tapirus terrestris) and other fruit-eating animals, or frugivores. This behavior releases forms of nitrogen, a key element in plant growth.

A study supported ...

Boston - A national group of pediatric addiction medicine experts have released newly-established principles of care for young adults with substance use disorder. Led by the Grayken Center for Addiction at Boston Medical Center, the collection of peer-reviewed papers was developed to guide providers on how to treat young adults with substance use disorder given their age-specific needs, as well as elevate national discussions on addressing these challenges more systematically.

Published in Pediatrics, the 11-paper supplement is the result of a convening of national experts in the treatment of young adults to determine the most important principles to address when caring for this unique population of patients with substance use disorder. ...

Liquids are ubiquitous in Nature: from the water that we consume daily to superfluid helium which is a quantum liquid appearing at temperatures as low as only a few degrees above the absolute zero. A common feature of these vastly different liquids is being self-bound in free space in the form of droplets. Understanding from a microscopic perspective how a liquid is formed by adding particles one by one is a significant challenge.

Recently, a new type of quantum droplets has been experimentally observed in ultracold atomic systems. These ones ...

Researchers from Skoltech and the University of Texas Medical Branch (US) have shown how optoacoustics can be used for monitoring skin water content, a technique which is promising for medical applications such as tissue trauma management and in cosmetology. The paper outlining these results was published in the Journal of Biophotonics.

(swelling caused by fluid accumulation) or dehydration, which can also have cosmetic impacts. Right now, electrical, mechanical and spectroscopic methods can be used to monitor water content in tissues, but there is no accurate and noninvasive technique that would also provide a high resolution and significant probing depth required for potential clinical applications.

Sergei Perkov of the Skoltech Center for Photonics ...

COLUMBUS, Ohio - "Buy low and sell high" says the old adage about investing in the stock market.

But a relatively new type of investment fund is luring unsophisticated investors into buying when values are at their highest, resulting in losses almost immediately, a new study has found.

The lure? Buying into trendy investment areas like cannabis, cybersecurity and work-from-home businesses.

"As soon as people buy them, these securities underperform as the hype around them vanishes," said Itzhak Ben-David, co-author of the study and professor of finance at The Ohio State University's Fisher College of Business.

"They appeal to people who are not sophisticated ...

New Rochelle, NY, January 15, 2021--The biodistribution of adeno-associated virus (AAV) gene transfer vectors can be measured in nonhuman primates using a new method. The method quantifies whole-body and organ-specific AAV capsids from 1 to 72 hours after administration. Study design and results are presented in the peer-reviewed journal Human Gene Therapy. Click here to read the full-text article free on the Human Gene Therapy website through February 15, 2021.

AAV capsids were labeled with I-124 and delivered using two routes of administration: intravenous and directly into the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). Biodistribution was measured by quantitative positron emission tomography (PET) at 1, 24, 48, and 72 hours after AAV administration. Two AAV vectors - AAVrsh.10 and AAV9 - were compared.

"Following ...

HAMILTON, ON, Jan. 15, 2021 -- A team of neuroscientists and engineers at McMaster University has created a nasal spray to deliver antipsychotic medication directly to the brain instead of having it pass through the body.

The leap in efficiency means patients with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and other conditions could see their doses of powerful antipsychotic medications cut by as much as three quarters, which is expected to spare them from sometimes-debilitating side effects while also significantly reducing the frequency of required treatment.

The new method delivers medication in a spray that reaches the brain directly through ...