(Press-News.org) There are high hopes for the next generation of high energy-density lithium metal batteries, but before they can be used in our vehicles, there are crucial problems to solve. An international research team led by Chalmers University of Technology, Sweden, has now developed concrete guidelines for how the batteries should be charged and operated, maximising efficiency while minimising the risk of short circuits.

Lithium metal batteries are one of several promising concepts that could eventually replace the lithium-ion batteries which are currently widely used - particularly in various types of electric vehicles.

The big advantage of this new battery type is that the energy density can be significantly higher. This is because one electrode of a battery cell - the anode - consists of a thin foil of lithium metal, instead of graphite, as is the case in lithium-ion batteries. Without graphite, the proportion of active material in the battery cell is much higher, increasing energy density and reducing weight. Using lithium metal as the anode also makes it possible to use high-capacity materials at the other electrode - the cathode. This can result in cells with three to five times the current level of energy-density.

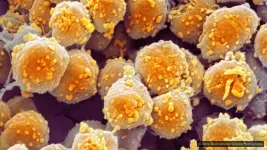

The big problem, however, is safety. In two recently published scientific articles in the prestigious journals Advanced Energy Materials and Advanced Science, researchers from Chalmers University of Technology, together with colleagues in Russia, China and Korea, now present a method for using the lithium metal in an optimal and safe way. It results from designing the battery in such a way that, during the charging process, the metal does not develop the sharp, needle-like structures known as dendrites, which can cause short circuits, and, in the worst cases, lead to the battery catching fire. Safety during charging and discharging is the key factor.

"Short circuiting in lithium metal batteries usually occurs due to the metal depositing unevenly during the charging cycle and the formation of dendrites on the anode. These protruding needles cause the anode and the cathode to come into direct contact with one another, so preventing their formation is therefore crucial. Our guidance can now contribute to this," says researcher Shizhao Xiong at the Department of Physics at Chalmers.

There are a number of different factors that control how the lithium is distributed on the anode. In the electrochemical process that occurs during charging, the structure of the lithium metal is mainly affected by the current density, temperature and concentration of ions in the electrolyte.

The researchers used simulations and experiments to determine how the charge can be optimised based on these parameters. The purpose is to create a dense, ideal structure on the lithium metal anode.

"Getting the ions in the electrolyte to arrange themselves exactly right when they become lithium atoms during charging is a difficult challenge. Our new knowledge about how to control the process under different conditions can contribute to safer and more efficient lithium metal batteries," says Professor Aleksandar Matic from Chalmers' Department of Physics.

INFORMATION:

More about: The research project

The international research collaboration between Sweden, China, Russia and Korea is led by Professor Aleksandar Matic and researcher Shizhao Xiong at the Department of Physics at Chalmers. The research in Sweden is funded by FORMAS, STINT, the EU and Chalmers Areas of Advance.

More about: The scientific publications

The scientific article 'Insight into the Critical Role of Exchange Current Density on Electrodeposition Behavior of Lithium Metal' has been published in Advanced Science. The article is written by Yangyang Liu, Xieyu Xu, Matthew Sadd, Olesya O. Kapitanova, Victor A. Krivchenko, Jun Ban, Jialin Wang, Xingxing Jiao, Zhongxiao Song, Jiangxuan Song, Shizhao Xiong and Aleksandar Matic.

The researchers are active at Lomonosov Moscow State University and the Moscow Institute of Physics and Technology in Russia, Xi'an Jiaotong University in China and at Chalmers University of Technology.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/advs.202003301

The scientific article 'Role of Li-Ion Depletion on Electrode Surface: Underlying Mechanism for Electrodeposition Behavior of Lithium Metal Anode' has been published in Advanced Energy Materials. The article is written by Xieyu Xu, Yangyang Liu, Jang-Yeon Hwang, Olesya O. Kapitanova, Zhongxiao Song, Yang-Kook Sun, Aleksandar Matic and Shizhao Xiong.

The researchers are active at Lomonosov Moscow State University, Russia, Xi'an Jiaotong University in China, Chonnam National University and Hanyang University in Korea, as well as at Chalmers University of Technology.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/aenm.202002390

More about: Next generation batteries

There are a number of battery concepts which researchers hope will eventually be able to replace today's lithium-ion batteries. Solid state batteries, lithium-sulphur batteries and lithium air batteries are three oft-mentioned examples. In all these concepts, lithium metal needs to be used on the anode side to match the capacity of the cathode and maximise the energy density of the cell.

The goal is to produce safe, high energy-density batteries that take us further, at lower cost - both economically and environmentally. So far, researchers estimate that a breakthrough to the next generation of batteries is at least ten years away.

At Chalmers, research is conducted in a number of projects in the field of batteries and the researchers participate in both national and international collaborations and are part of the large European initiative 2030+ in the BIGMAP project.

For more information contact:

Shizhao Xiong,

Researcher, Department of Physics,

Chalmers University of Technology, Sweden,

+46 31 7726284,

shizhao.xiong@chalmers.se

Aleksandar Matic,

Professor, Department of Physics,

Chalmers University of Technology, Sweden,

+46 31 772 51 76,

matic@chalmers.se

New research suggests a unique program called Moms2B at The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center shows a reduction in adverse pregnancy outcomes in communities disproportionately affected by these public health issues.

The study, led by researchers Courtney Lynch and Erinn Hade and published in the Journal of Maternal and Child Health, indicates that women who attended at least two Moms2B sessions may have lower rates of preterm birth, low birth weight and infant mortality compared to women who only received individual care.

"When we started the program 10 years ago, ...

New study identifies a bizarre new species suggesting that giant marine lizards thrived before the asteroid wiped them out 66 million years ago.

A new species of mosasaur - an ancient sea-going lizard from the age of dinosaurs - has been found with shark-like teeth that gave it a deadly slicing bite.

Xenodens calminechari, from the Cretaceous of Morocco, had knifelike teeth that were packed edge to edge to make a serrated blade and resemble those of certain sharks. The cutting teeth let the small, agile mosasaur, about the size of a small porpoise, punch above its weight, cutting fish in half and taking large bites from bigger animals.

Dr Nick Longrich, Senior Lecturer at the Milner Centre for Evolution at the University of Bath and lead author on ...

Clumsy kids can be as aerobically fit as their peers with better motor skills, a new Finnish study shows. The results are based on research conducted at the Faculty of Sport and Health Sciences of the University of Jyväskylä and the Institute of Biomedicine of the University of Eastern Finland, and they were published in Translational Sports Medicine.

Aerobic fitness doesn't go hand in hand with motor skills

According to the general perception, fit kids also have good motor skills, while low aerobic fitness has been thought to be a link ...

A group of international scientists, including an Australian astrophysicist, has used knowhow from gravitational wave astronomy (used to find black holes in space) to study ancient marine fossils as a predictor of climate change.

The research, published in the journal Climate of the Past, is a unique collaboration between palaeontologists, astrophysicists and mathematicians - to improve the accuracy of a palaeo-thermometer, which can use fossil evidence of climate change to predict what is likely to happen to the Earth in coming decades.

Professor Ilya Mandel, from the ARC Centre of Excellence in Gravitational Wave Discovery (OzGrav), and colleagues, studied biomarkers left behind by tiny single-cell organisms called archaea in the distant past, including the Cretaceous period ...

In the strawberry nursery industry, a nursery's reputation relies on their ability to produce disease- and insect-free plants. The best way to produce clean plants is to start with clean planting stock. Many nurseries struggle with angular leaf spot of strawberry, a serious disease that can result in severe losses either by directly damaging the plant or indirectly through a violation of quarantine standards within the industry.

Angular leaf spot is caused by the bacterial pathogen Xanthomonas fragariae. Current management strategies rely primarily ...

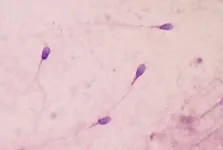

Chemotherapy and radiation treatments are known to cause harsh side effects that patients can see or feel throughout their bodies. Yet there are additional, unseen and often undiscussed consequences of these important therapies: the impacts on their future pregnancies and hopes for healthy children.

Extensive evidence shows that chemotherapy and radiation treatments are genotoxic, meaning they can mutate the DNA and damage chromosomes in patients' cancerous and noncancerous cells alike. When this occurs in a germline cell - which are egg cells in women and sperm in men - it can lead to serious fetal and birth ...

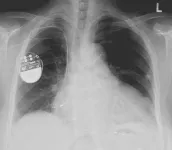

A new type of ultra-efficient, nano-thin material could advance self-powered electronics, wearable technologies and even deliver pacemakers powered by heart beats.

The flexible and printable piezoelectric material, which can convert mechanical pressure into electrical energy, has been developed by an Australian research team led by RMIT University.

It is 100,000 times thinner than a human hair and 800% more efficient than other piezoelectrics based on similar non-toxic materials.

Importantly, researchers say it can be easily fabricated through a cost-effective and commercially scalable method, using ...

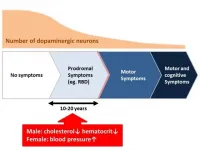

A research team led by Nagoya University in Japan has found that blood pressure, the hematocrit (the percentage of red blood cells in blood), and serum cholesterol levels change in patients with Parkinson's disease long before the onset of motor symptoms. This finding, which was recently published online in Scientific Reports, may pave the way for early diagnosis and treatment of the disease.

Parkinson's disease, the second most common disease affecting the nervous system after Alzheimer's disease, is caused by a deficiency in a neurotransmitter called dopamine. It is known that more than half of all dopaminergic neurons are already lost in patients with Parkinson's disease in the stage wherein they ...

India has an energy problem. It currently relies heavily on coal and consumer demand is expected to double by 2040, making its green energy targets look out of reach. Part of the solution could come from harvesting energy from footsteps, say Hari Anand and Binod Kumar Singh from the University of Petroleum and Energy Studies in Dehradun, India. Their new study, published in the De Gruyter journal Energy Harvesting and Systems, shows that Indian attitudes towards power generated through piezoelectric tiles are overwhelmingly positive.

Cities like Delhi and Mumbai are famously crowded, especially at railway stations, temples and big commercial buildings. This led researchers to wonder whether piezoelectric tiles, which produce ...

Researchers have used the world's smallest, smartphone-sized DNA sequencing device to monitor hundreds of different bacteria in a river ecosystem.

Writing in the journal eLife, the interdisciplinary team from the University of Cambridge, UK, provide practical and analytical guidelines for using the device, called the MinION (from Oxford Nanopore Technologies), to monitor freshwater health. Their guidelines promise a significantly more cost-effective and simple approach to this work outside the lab, compared to existing methods.

Rowers and swimmers in Cambridge are regularly affected by waterborne infections such as Weil's disease, sometimes leading to public closures of the city's iconic waterways. Monitoring the microbial species in freshwater ...