Media Contact: Rachel Butch, rbutch1@jhmi.edu

In a study in mice and human cells, Johns Hopkins Medicine researchers say that they have developed a tiny, yet effective method for preventing premature birth. The vaginally delivered treatment contains nanosized (billionth of a meter) particles of drugs that easily penetrate the vaginal wall to reach the uterine muscles and prevent them from contracting. If proven effective in humans, the treatment could be one of the only clinical options available to prevent preterm labor. The FDA has recommended removing Makena (17-hydroxyprogesterone caproate), the only approved medicine for this purpose, from the market.

The study was published Jan. 13, 2020, in the journal Science Translational Medicine.

There are an estimated 15 million premature births each year, making it the number one cause of infant mortality worldwide. Few indicators can predict which pregnancies will result in a preterm birth, but inflammation in the reproductive tract is a contributing factor in approximately one-third of all cases. This symptom not only puts babies at risk of being born with low birth weight and underdeveloped lungs, but also has been linked to brain injuries in the developing fetus.

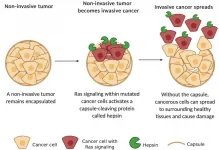

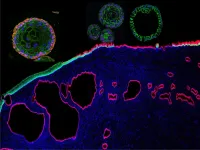

The newly reported experimental therapy uses technology developed by scientists at the Johns Hopkins Center for Nanomedicine. Its active ingredients are two drugs: progesterone, a hormone that regulates female reproduction, and trichostatin A, an inhibitor of the enzyme histone deacetylase, which regulates gene expression. To prepare the treatment, the drugs are first ground down into miniature crystals, about 200-300 nanometers in diameter, or smaller than a typical bacterium. Then, the nanocrystals are coated with a stabilizing compound that keeps them from getting caught in the body's protective mucus layers, which absorb and sweep away foreign particles.

"This means we can use far less drug to efficiently reach other parts of the female reproductive tract," says Laura Ensign, Ph.D., associate professor of ophthalmology, with a secondary appointment in gynecology and obstetrics at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, co-author of the study and an expert on nanomedicine and drug delivery systems.

To test their therapy, the researchers used mice that were engineered to mimic inflammation-related conditions that would lead to preterm labor in humans. They found that the experimental treatment prevented the mice from entering premature labor. Neurological tests of mouse pups born to mothers that had received the treatment revealed no abnormalities.

The researchers also applied the drug combination to human uterine cells grown in the lab. The drug combination, they report, decreased contractions in the test samples.

Additional laboratory tests of the experimental treatment are planned to evaluate its safety before considering trials in humans.

LOOKING BACK DECADES SHOWS HOSPITALIZED PATIENTS NEED MORE THAN MOVEMENT TO PREVENT DANGEROUS CLOTS

Media Contact: Michael E. Newman, mnewma25@jhmi.edu

Based on a systematic review of scientific studies dating back nearly 70 years, researchers at Johns Hopkins Medicine and collaborating institutions suggest that ambulation -- walking or exercising without assistance -- is not sufficient alone as a preventive measure against venous thromboembolism (VTE), a potentially deadly condition in which a blood clot forms, often in the deep veins of the leg, groin or arm (known as a deep vein thrombosis) and may dislodge. If that happens, the clot will travel via the bloodstream to lodge in the lungs and cause tissue damage or death from reduced oxygen (known as a pulmonary embolism).

The researchers presented their findings in the Dec. 8, 2020, issue of the Canadian Medical Association Journal Open.

According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, VTE annually affects some 300,000 to 600,000 individuals in the United States, and kills between 60,000 to 100,000 of those stricken. Among the groups at highest risk are hospitalized patients, especially those who undergo surgery.

Since the 1950s, ambulation -- in the form of walking or foot/leg exercises -- as soon and as often as possible following surgery has been recommended as a means of reducing the threat of VTE in high-risk patients. The latest study was conducted to see if ambulation is enough or if other measures -- primarily medications known as anticoagulants or blood thinners -- are needed.

The researchers reviewed nearly 21,000 scientific papers from 1951 through April 2020 and used predefined scoring criteria to select the 18 most relevant studies. These consisted of eight retrospective and two prospective studies, seven randomized clinical trials and one secondary analysis of a randomized clinical trial.

"Our systematic review revealed little evidence to support ambulation alone as an adequate means of preventing VTEs," says Elliott Haut, M.D., Ph.D., associate professor of surgery at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine and senior author of the study.

The findings, Haut says, are concerning because ambulation is commonly thought to be effective as the sole prophylaxis used to avoid VTEs. In fact, he adds, several national and international clinical guidelines recommend this course of action.

"It's a mistaken belief that often leads to doctors discontinuing what they perceive as unnecessary medication or nurses presenting ambulation as an alternative prophylaxis to patients," says study lead author Brandyn Lau, M.P.H., assistant professor of radiology and radiological science at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. "On the contrary, there is overwhelming evidence supporting medications to prevent VTE in nearly every applicable population admitted to a hospital."

Haut, Lau and their collaborators hope these findings will help change the long-standing misconception that ambulation can prevent VTEs on its own and persuade physicians to take a more comprehensive approach.

JOHNS HOPKINS GYNECOLOGIC CANCER EXPERTS TO ADDRESS DISPARITIES IN CANCER CARE

Media Contact: Marisol Martinez, mmart150@jhmi.edu

Thanks to a nearly $400,000 grant from the American Cancer Society and Pfizer, three gynecologic cancer experts from the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine and the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health will address widespread race-related barriers and disparities in the delivery of care that may affect the outcomes of gynecologic cancer patients. The grant, awarded under the Addressing Racial Disparities in Cancer Care Competitive Grant Program, will enable the team to develop a scalable (adaptable) and ultimately sustainable way to identify and address the social determinants of health that contribute to these concerns.

The researchers for the Johns Hopkins grant are co-principal investigator Anna Beavis, M.D., M.P.H., and Stephanie Wethington, M.D., M.Sc., assistant professors of gynecology and obstetrics in the Division of Gynecologic Oncology at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, and co-principal investigator Anne Rositch, M.S.P.H., Ph.D., associate professor of epidemiology at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

The project expands on a pilot program started in 2017 in collaboration with Hopkins Community Connection (formerly Health Leads) that identified and addressed challenges disproportionately affecting Black patients -- such as access to basic needs like food, housing and transportation -- which have now been exacerbated by the disparate effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on the Black community. The team hopes that this expansion will be widely applied in the future and lead to more equitable outcomes for all women treated for gynecologic cancers.

"With the pandemic, our minority patients have been affected the most," says Beavis. "While basic needs have always been more prevalent in underserved populations, the pandemic has brought additional financial and other resource strain to our Black patient community, so this grant is very timely."

Gynecologic cancer is any cancer that starts in a woman's reproductive organs (cervix, ovaries, uterus, vagina and vulva). The incidence of gynecologic cancers can vary by cancer type and race or ethnicity.

According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, about 94,000 women are diagnosed with gynecologic cancers each year. Black and Hispanic women get more cervical cancer associated with HPV than women of other races or ethnicities, possibly because of less access to screening tests and follow-up treatment.

INFORMATION: