No insect crisis in the Arctic - yet

A new study shows that rare insects are declining in the Arctic, suggesting that climatic changes may favour common species.

2021-01-19

(Press-News.org) Climate change is more pronounced in the Arctic than anywhere else on the planet, raising concerns about the ability of wildlife to cope with the new conditions. A new study shows that rare insects are declining, suggesting that climatic changes may favour common species.

As part of a new volume of studies on the global insect decline, researchers are presenting the first Arctic insect population trends from a 24-year monitoring record of standardized insect abundance data from North-East Greenland.

The work took place during 1996-2018 as part of the ecosystem-based monitoring program Greenland Ecosystem Monitoring at the field station Zackenberg, located in the world's largest national park with high-arctic climate.

At this remote location, researchers can truly isolate the effects of climate change on insects, because there is no agriculture or industry in the area, nor are there any cities within the nearest thousand kilometres of the field station.

"Data from Europe, North America and the tropics show that many species of insects are in strong decline. Luckily, we are now able to show that there is no profound crash in high arctic insect populations," explains senior scientist Toke T. Høye, Department of Bioscience and Arctic Research Center at Aarhus University, who led the study.

No dramatic decline in Arctic

The results of the study reveal how insects differ markedly in their population trends and show multi-faceted responses to climate change. Climate outside the summer season and other factors than temperature can be very important.

While the study provides strong evidence of insects responding to climate change, it is unlikely that widespread insect declines would be caused by the same single factor. The authors indicate that the range of long-term insect responses may in part be due to the diversity of life styles and adaptations to extreme conditions by this high-arctic insect community.

The study is just published in the top-tier journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

"It is too early to say that we do not have an insect crisis in the Arctic. Our data shows that a range of rare taxa are in decline, while more common insects are doing OK," says Toke T. Høye.

Effects of climate changes

One key impact of climate change is that it extends the growing seasons in the Arctic. This often means that there is an even longer period in which the ground repeatedly freezes and thaws.

"This period is a big challenge for many insects and climate change is thus especially affecting insects during parts of the year where they are in a dormant stage. The insects are tricked into expecting spring to arrive, just to be hit by hard frost afterwards," explains Toke T. Høye.

During the past years, the research team at the field station at Zackenberg has also observed that permafrost thawing dries out the top soil layer. This affects insects in their larval stages and can have delayed effects on adult insect populations. Such effects may only become apparent after a number of years and can have important cascading effects through the food web.

To understand changes in insect population dynamics, long time series of standardized data, such as those from Zackenberg are critically important. These new results from the Arctic draw a more complex picture of insect responses to climate change than anticipated and highlight the importance of continued support for long-term monitoring.

INFORMATION:

Contact: Senior scientist, Toke T. Høye, Aarhus University, Denmark. Mail: tth@bios.au.dk; phone: +45 30183122.

Link to the paper: https://www.pnas.org/content/118/2/e2002557117

[Attachments] See images for this press release:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-01-19

Organoids are increasingly being used in biomedical research. These are organ-like structures created in the laboratory that are only a few millimetres in size. Organoids can be used to study life processes and the effect of drugs. Because they closely resemble real organs, they offer several advantages over other cell cultures.

Now there are also organoid models developed for the cervix. This part of the female body is particularly at risk to develop cancers. By creating novel organoid models, a group led by Cindrilla Chumduri (Würzburg), Rajendra Kumar Gurumurthy (Berlin) and Thomas F. Meyer ...

2021-01-19

WHAT:

Healthcare providers must be able to explain the latest data supporting the safety and efficacy of vaccines for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) so they can strongly encourage vaccination when appropriate while acknowledging that uncertainty and unknowns remain. This message comes from a new commentary co-authored by Anthony S. Fauci, M.D., director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), part of the National Institutes of Health, and other leading NIAID scientists in the journal Annals of Internal Medicine.

The commentary provides an overview of the seven COVID-19 vaccines furthest along in development in the United States. For each vaccine candidate, the authors describe ...

2021-01-19

Understanding how the natural world works enables us to mimic it for the benefit of humankind. Think of how much we rely on batteries. At the core is understanding molecular structures and the behavior of electrons within them. Calculating the energy differences between a molecule's electronic ground and excited spin states helps us understand how to better use that molecule in a variety of chemical, biomedical and industrial applications. We have made much progress in molecules with closed-shell systems, in which electrons are paired up and stable. Open-shell systems, on the ...

2021-01-19

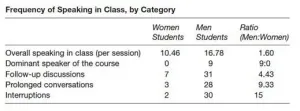

Men speak 1.6 times more often than women in college classrooms, revealing how gender inequities regarding classroom participation still exist, according to a Dartmouth study. By comparison, women are more hesitant to speak and are more apt to use apologetic language. The findings are published in Gender & Society.

When students didn't have to raise their hands to participate in class, men spoke three times more often than women. "You would think that it would be more equitable for students to not have to raise their hands to speak in class because then anyone could talk ...

2021-01-19

RICHLAND, Wash.--E-cigarettes stress and inflame the lungs of rats, compromising important regulatory proteins through exposure, according to research recently published in the journal Redox Biology. The findings, made possible by a biomolecular technique developed by researchers at the U.S. Department of Energy's Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, reveal that vaping induces subtle structural changes in proteins, marking the first time researchers have measured such damage. The results suggest that common compounds in the electronic alternative to conventional cigarettes are not without their own harms.

After exposing rats to e-cigarette vapor for three one-hour sessions ...

2021-01-19

Some say future wars will be fought over water, and a billion people around the world are already struggling to find enough water to live.

Now, researchers at the National University of Singapore (NUS) are coming to the rescue. They have created a substance that extracts water from air without any external power source.

In the earth's atmosphere, there is water that can fill almost half a trillion Olympic swimming pools. But it has long been overlooked as a source for potable water.

To extract water from this under utilised source, a team led by Professor Ho Ghim Wei from the NUS Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering created a type of aerogel, a solid material that weighs almost nothing. Under the microscope, it looks like a sponge, but it ...

2021-01-19

University of South Australia scientists have developed the world's first test to accurately predict mood disorders in people, based on the levels of a specific protein found in the brain.

Links between low levels of mature brain-derived neurotrophic factor (mBDNF) and depression are well known but, until now, it hasn't been possible to distinguish between the three forms of the BDNF protein in blood samples.

The mature form promotes the growth of neurons and protects the brain, but the other two BDNF forms - its precursor and the prodomain of BDNF - bind to different receptors, causing nerve degeneration ...

2021-01-19

SINGAPORE, 19 January 2021 - Duke-NUS Medical School researchers, together with collaborators in Singapore, have designed armoured immune cells that can attack recurring cancer in liver transplant patients, while temporarily evading immunosuppressant drugs patients take to avoid organ rejection. The findings were published in the journal Hepatology.

Hepatocellular carcinoma is the most common type of primary liver cancer and the sixth most common cancer worldwide. It often develops in people with chronic liver disease following hepatitis B infection.

A common treatment for hepatocellular carcinoma is to completely ...

2021-01-19

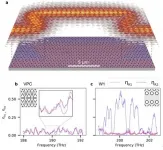

Topologically tailored photonic crystals (PhC) have opened up the possibility for attaining robust unidirectional transport of classical and quantum systems. The demand for unprecedented guiding capabilities that support unhindered transport around imperfections and sharp corners at telecom wavelengths, without the need for any optimization, is fundamental for efficient distribution of information through dense on-chip photonic networks. However, transport properties of experimental realizations of such topologically non-trivial states have been inferred by transmission measurements and even though robustness ...

2021-01-19

Overview:

A team of researchers led by Assistant Professor Yuki Arakawa (Toyohashi University of Technology, Japan) has successfully developed sulfur-containing liquid crystal (LC) dimer molecules1) with oppositely directed ester bonds, which exhibit a helical liquid crystal phase, viz. twist-bend nematic (NTB) phase, 2) over a wide temperature range, including room temperature. Collaboration with a team at the Advanced Light Source research facility (Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, USA) revealed that the ester bond direction in the molecular structures largely impacts the pitch lengths of helical nanostructures in the NTB phase. It is expected that this molecular design ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] No insect crisis in the Arctic - yet

A new study shows that rare insects are declining in the Arctic, suggesting that climatic changes may favour common species.