Spike proteins of SARS-CoV-2 relatives can evolve against immune responses

Viral relatives of SARS-CoV-2 can evolve to evade the human immune system, posing questions about the long-term effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines

2021-01-19

(Press-News.org) Scientists have shown that two species of seasonal human coronavirus related to SARS-CoV-2 can evolve in certain proteins to escape recognition by the immune system, according to a study published today in eLife.

The findings suggest that, if SARS-CoV-2 evolves in the same way, current vaccines against the virus may become outdated, requiring new ones to be made to match future strains.

When a person is infected by a virus or vaccinated against it, immune cells in their body will produce antibodies that can recognise and bind to unique proteins on the virus' surface known as antigens. The immune system relies on being able to 'remember' the antigens that relate to a specific virus in order to provide immunity against it. However, in some viruses, such as the seasonal flu, those antigens are likely to change and evolve in a process called antigenic drift, meaning the immune system may no longer respond to reinfection.

"Some coronaviruses are known to reinfect humans but it is not clear to what extent this is due to our immune memory fading or antigenic drift," says first author Kathryn Kistler, a PhD student at the Vaccine and Infectious Disease Division, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, US. "We wanted to investigate whether there is any evidence of coronaviruses related to SARS-CoV-2 evolving to evade our immune responses."

The research team looked at the four seasonal human coronaviruses (HCoVs) which are related to SARS-CoV-2 but typically cause milder symptoms, such as the common cold. HCoVs have been circulating in the human population for 20-60 years, meaning their antigens would likely have faced pressure to evolve against our immune system.

The team used a variety of computational methods to compare the genetic sequences of many different strains of the viruses, enabling them to see how they have evolved over the years. They were especially interested in any changes that might have occurred in viral proteins that could contain antigens, such as spike proteins - the ray-like projections on the surface of coronaviruses that are particularly exposed to our immune system.

The researchers found a high rate of evolution in the spike proteins of two of the four viruses, OC43 and 229E. Nearly all of the beneficial mutations appeared in a specific region of the spike proteins called S1, which helps the virus infect human cells. This suggests that reinfection by these two viruses can occur as a result of antigenic drift as they evolve to escape recognition by the immune system.

The team also estimated that beneficial mutations in the spike proteins of OC43 and 229E appear roughly once every two to three years, about half to one-third of the rate seen in the flu virus strain, H3N2.

"Due to the high complexity and diversity of HCoVs, it is not entirely clear if this means that other coronaviruses, such as SARS-CoV-2, will evolve in the same way," explains senior author Trevor Bedford, Principal Investigator and Associate Member at the Vaccine and Infectious Disease Division, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center. "The current vaccines against COVID-19, while highly effective, may need to be reformulated to match new strains, making it vital to continually monitor the evolution of the virus' antigens."

INFORMATION:

Reference

The paper 'Evidence for adaptive evolution in the receptor-binding domain of seasonal coronaviruses OC43 and 229E' can be freely accessed online at https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.64509. Contents, including text, figures and data, are free to reuse under a CC BY 4.0 license.

Media contacts

Emily Packer, Media Relations Manager

eLife

e.packer@elifesciences.org

01223 855373

Claire Hudson, Communications Manager

Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center

media@fredhutch.org

About eLife

eLife is a non-profit organisation created by funders and led by researchers. Our mission is to accelerate discovery by operating a platform for research communication that encourages and recognises the most responsible behaviours. We work across three major areas: publishing, technology and research culture. We aim to publish work of the highest standards and importance in all areas of biology and medicine, including Evolutionary Biology, while exploring creative new ways to improve how research is assessed and published. We also invest in open-source technology innovation to modernise the infrastructure for science publishing and improve online tools for sharing, using and interacting with new results. eLife receives financial support and strategic guidance from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation, the Max Planck Society and Wellcome. Learn more at https://elifesciences.org/about.

To read the latest Evolutionary Biology research published in eLife, visit https://elifesciences.org/subjects/evolutionary-biology.

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-01-19

DENVER--A study in the Journal of Thoracic Oncology (JTO) comparing surgeries performed at one Chinese hospital in 2019 with a similar date range during the COVID-19 pandemic found that routine thoracic surgery and invasive examinations were performed safely. The JTO is the official journal of the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer.

Wentao Fang, MD, chief director of the Department of Thoracic Surgery, Shanghai Chest Hospital, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, Shanghai, China and his colleagues analyzed the number of elective procedures ...

2021-01-19

Scientists are urging global policymakers and funders to think of fish as a solution to food insecurity and malnutrition, and not just as a natural resource that provides income and livelihoods, in a newly-published paper in the peer-reviewed journal Ambio. Titled "Recognize fish as food in policy discourse and development funding," the paper argues for viewing fish from a food systems perspective to broaden the conversation on food and nutrition security and equity, especially as global food systems will face increasing threats from climate change.

The "Fish as Food" paper, authored by scientists and policy experts from Michigan State University, Duke ...

2021-01-19

HOUSTON - (Jan. 19, 2021) - Microscopic bubbles can tell stories about Earth's biggest volcanic eruptions and geoscientists from Rice University and the University of Texas at Austin have discovered some of those stories are written in nanoparticles.

In an open-access study published online in Nature Communications, Rice's Sahand Hajimirza and Helge Gonnermann and UT Austin's James Gardner answered a longstanding question about explosive volcanic eruptions like the ones at Mount St. Helens in 1980, the Philippines' Mount Pinatubo in 1991 or Chile's Mount Chaitén in 2008.

Geoscientists have long sought to use tiny bubbles in erupted lava and ash to reconstruct some of the conditions, ...

2021-01-19

Social distancing and working from home help prevent transmission of the novel coronavirus but can be conducive to unhealthy behavior such as bingeing on fast food or spending more time in a chair or on a couch staring at a screen, and generally moving about less during the day. Scientists believe the reduction in physical activity experienced during the first few months of the pandemic could lead to an annual increase of more than 11.1 million in new cases of type 2 diabetes and result in more than 1.7 million deaths.

The estimates are presented by researchers at São Paulo State University (UNESP), Brazil, in a review article published in Frontiers in Endocrinology. The authors stress that there is an "urgent need" to recommend physical activity during ...

2021-01-19

Just how close are the world's countries to achieving the Paris Agreement target of keeping climate change limited to a 1.5°C increase above pre-industrial levels?

It's a tricky question with a complex answer. One approach is to use the remaining carbon budget to gauge how many more tonnes of carbon dioxide we can still emit and have a chance of staying under the target laid out by the 2015 international accord. However, estimates of the remaining carbon budget have varied considerably in previous studies because of inconsistent approaches and assumptions used by researchers.

Nature Communications Earth and Environment just published a paper by a group of researchers led by Damon Matthews, professor in the Department of Geography, Planning and Environment. In it, ...

2021-01-19

TAMPA, Fla. - Cells need energy to survive and thrive. Generally, if oxygen is available, cells will oxidize glucose to carbon dioxide, which is very efficient, much like burning gasoline in your car. However, even in the presence of adequate oxygen, many malignant cells choose instead to ferment glucose to lactic acid, which is a much less efficient process. This metabolic adaptation is referred to as the Warburg Effect, as it was first described by Otto Warburg almost a century ago. Ever since, the conditions that would evolutionarily select for cells to exhibit a Warburg Effect have been in debate, as it is much less efficient and produces toxic waste ...

2021-01-19

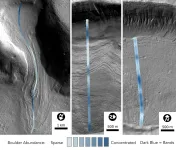

In a new paper published today in the Proceedings of the National Academies of ScienceS (PNAS), planetary geologist Joe Levy, assistant professor of geology at Colgate University, reveals a groundbreaking new analysis of the mysterious glaciers of Mars.

On Earth, glaciers covered wide swaths of the planet during the last Ice Age, which reached its peak about 20,000 years ago, before receding to the poles and leaving behind the rocks they pushed behind. On Mars, however, the glaciers never left, remaining frozen on the Red Planet's cold surface for more than 300 million years, covered in debris. "All the rocks and sand carried on that ice have remained ...

2021-01-19

ATLANTA--Early in the U.S. COVID-19 pandemic, unemployment claims were largely driven by state shutdown orders and the nature of a state's economy and not by the virus, according a new article by Georgia State University economists.

David Sjoquist and Laura Wheeler found no evidence the Payroll Protection Program (PPP) affected the number of initial claims during the first six weeks of the pandemic.

Their research explores state differences in the magnitude of weekly unemployment insurance claims for the weeks ending March 14 through April 25 by focusing on three factors: the impact of COVID-19, the effects of state economic structures and state orders closing non-essential ...

2021-01-19

The offspring of older animals often have a lower chance of survival because the parents are unable to take care of their young as well as they should. The Seychelles warbler is a cooperatively breeding bird species, meaning that parents often receive help from other birds when raising their offspring. A study led by biologists from the University of Groningen shows that the offspring of older females have better prospects when they are surrounded by helpers. This impact of social behaviour on reproductive success is described in a paper that was published ...

2021-01-19

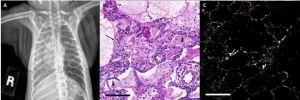

Philadelphia, January 19, 2021 - Aged, wild-caught African green monkeys exposed to the SARS-CoV-2 virus developed acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) with clinical symptoms similar to those observed in the most serious human cases of COVID-19, report researchers in The American Journal of Pathology, published by Elsevier. This is the first study to show that African green monkeys can develop severe clinical disease after SARS-CoV-2 infection, suggesting that they may be useful models for the study of COVID-19 in humans.

"Animal models greatly enhance our understanding of diseases. The lack of an animal model for severe manifestations of COVID-19 has hampered our understanding of this form of the disease," explained lead investigator Robert V. Blair, DVM, PhD, ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Spike proteins of SARS-CoV-2 relatives can evolve against immune responses

Viral relatives of SARS-CoV-2 can evolve to evade the human immune system, posing questions about the long-term effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines