(Press-News.org) Did you know that fleas, ants, and click beetles are capable of blazingly fast accelerations, with some up to 10^6 meters per square-second? Their quick movements make fast animals like the cheetah look like slowpokes.

A new study by a team that included Jake Socha, professor in biomedical engineering and mechanics in Virginia Tech's College of Engineering, published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academies of Sciences shows that a snap-through unbending movement of the body is the main reason for the clicking beetle's fast acceleration.

Most animals use muscle to move. For example, when we want to bend our elbow, our biceps and triceps contract. A muscle contracts by shortening to cause movement. In a small animal, such as the click beetle, muscle power is minimal due the muscles' small size, so quick movement happens in unique ways.

Take the three-phase process behind the beetle's clicking maneuver: latching, spring loading, and energy release. The insect amplifies its muscle power by using its muscle to initiate a series of springs and latches that trigger energy release, resulting in fast movement. The latches and springs enable the animal to bend its body and then unbend quickly, which results in a clicking motion, often resulting in a jump. Much is known about the jumping motion, but less is known about the quick unbending that comes before it.

Previously, the click beetle's small size and the internal locations of many of the parts of the system used in unbending posed a challenge to those studying these mechanisms. This is the first time the physical mechanisms of the internal spring in click beetles have been observed and measured using high-speed X-ray.

Socha worked on the study as part of a team of interdisciplinary experts, including Ophelia Bolmin, Aimy Wissa, and Alison Dunn, all in mechanical science and engineering at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign; Marianne Alleyne, in entomology at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign; and Kamel Fezzaa at Argonne National Laboratory.

As part of the three-phrase process, click beetles jump using a unique hinge-like tool in their thorax, just behind the head. Researchers used high-speed synchronton X-ray imaging at Argonne to analyze the beetle's motion of the hinge used for bending and unbending.

"The hinge mechanism has a peg on one side that stays latched onto a lip on the other side of the hinge," Alleyne said. "When the latch is released, there is an audible clicking sound and a quick unbending motion that causes the beetle's jump."

The click beetle's latch is located on the underside of its body, between the front and middle legs, composed of two hard parts of the exoskeleton. Prior to a click, the beetle stores energy in the system. When the latch is released, all of that energy is released and the front of the body rapidly flexes - the quick unbending - which throws the beetle into the air at a fast acceleration.

While investigating that process, the researchers discovered a portion of the spring mechanism used to store and quickly release energy in the click beetle. They found that the spring and latch mechanism located in the thorax could generate extreme accelerations when performing the clicking maneuver, reaching accelerations of more than 300 times that of the Earth's gravitational acceleration. This acceleration is what enables the beetles to launch itself into the air, to flip itself over or to move elsewhere.

The latch and spring mechanisms in these animals are similar to a bow and arrow, Socha explained. When launching the arrow with a bow, you pull the arrow back with your arm muscles and the energy is transferred to the bow and string. The energy is stored there until you release the arrow. The string recoil - when launching the arrow - has a much greater acceleration and power than if you were to throw the arrow using muscle power alone.

The team also found that nonlinear damping and elastic forces are behind the ultrafast release and snap-through buckling, a form of dynamic instability which enables the beetle to move quickly between two locations.

"We were surprised to find that the beetles use these basic engineering principles," said Wissa. "If an engineer wanted to build a device that jumps like a click beetle, they would likely design it the same way nature did. This work turned out to be a great example of how engineering can learn from nature and how nature demonstrates physics and engineering principles."

This discovery enabled researchers to develop an analytical framework that can be used to uncover the physical mechanics governing ultrafast motion in other small animals. Understanding how these small animals can generate extreme acceleration could lead to breakthroughs in small-scale robotics and small devices, potentially using similar snap-through methods to release energy on demand to produce ultrafast movements.

"Click beetles are fun to play with," said Socha. "Flip them on their back, and they pop into the air. But now we know that they're even cooler than that. It's exciting to discover that they evolved the mechanical trick of snap-through buckling, similar to a kids' jumping popper toy."

Socha is also the director of Biological Transport (BIOTRANS) at Virginia Tech. Wissa is also affiliated with aerospace engineering and the Carle Illinois College of Medicine. Dunn is also affiliated with the Carle Illinois College of Medicine and RAILtec. Alleyne is also affiliated with mechanical science and engineering and the Beckman Institute for Advanced Science and Technology at Illinois.

INFORMATION:

-- Written by Laura McWhinney

Countries where massive natural hazard events occur frequently are not more likely than others to make changes to reduce risks from future disasters. This is shown in an interdisciplinary Uppsala University study now published in Nature Communications.

Natural hazard events, such as storms, floods, and wildfires, entail huge and growing costs all over the world, but they can also be occasions for countries to implement risk-reducing changes. There is no research consensus on whether natural hazard events lead to policy modifications or, instead, contribute to stability and preservation of existing solutions. Knowledge in this area to date has been ...

JUPITER, FL - In a landmark neurobiology study, scientists from Scripps Research have discovered a memory gating system that employs the neurotransmitter dopamine to direct transient forgetting, a temporary lapse of memory which spontaneously returns.

The study adds a new pin to scientists' evolving map of how learning, memory and active forgetting work, says Scripps Research Neuroscience Professor Ron Davis, PhD.

"This is the first time a mechanism has been discovered for transient memory lapse," Davis says. "There's every reason to believe, because of conservation ...

An extra 290,000 pounds a year for lighting and cleaning because smog darkens and pollutes everything: with this cost estimate for the industrial city of Manchester, the English economist Arthur Cecil Pigou once founded the theory of environmental taxation. In the classic "The Economics of Welfare", the first edition of which was published as early as 1920, he proved that by allowing such "externalities" to flow into product prices, the state can maximise welfare. In 2020, exactly 100 years later, the political implementation of Pigou's insight has gained strength, important objections are being invalidated, and carbon pricing appears more efficient than regulations and bans according to a ...

Scientists from the CNRS, CNES, IRD, Sorbonne Université, l'Université Toulouse III - Paul Sabatier and their Australian colleagues*, with the support of the IPEV, have provided a comprehensive analysis on the evolution of Southern Ocean temperatures over the last 25 years. The research team has concluded that the slight cooling observed at the surface hides a rapid and marked warming of the waters, to a depth of up to 800 metres. The study points to major changes around the polar ice cap where temperatures are increasing by 0.04°C per decade, which could have serious consequences for Antarctic ice. Warm water is also rising rapidly to the surface, at a rate of 39 metres per decade, i.e. between three and ten ...

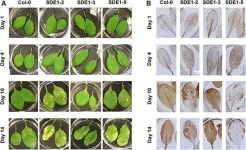

Citrus greening disease, also known as Huanglongbing (HLB), is devastating to the citrus industry, causing unprecedented amounts of damage worldwide. There is no known cure. Since the disease's introduction to the United States in the early 2000s, research efforts have increased exponentially. However, there is still a lack of information about the molecular mechanism behind the disease.

"Getting into the molecular details behind what contributes to citrus greening symptom development and disease progression is key to finding sustainable solutions to combat the pathogen," explained plant pathologist Wenbo Ma. "We bring the community one step closer to understanding these mechanisms ...

Understanding the genetic and environmental factors that enable some feral honey bee colonies to tolerate pathogens and survive the winter in the absence of beekeeping management may help lead to breeding stocks that would enhance survival of managed colonies, according to a study led by researchers in Penn State's College of Agricultural Sciences.

Feralization occurs when previously domesticated organisms escape to the wild and establish populations in the absence of human influence, explained lead researcher Chauncy Hinshaw, doctoral candidate in plant pathology and environmental microbiology.

"In the case of honey bees, colonies that escape domestication and establish in the wild provide an opportunity to study how environmental and genetic factors ...

Muscle structure and body size predict the athletic performance of Olympic athletes, such as sprinters. The same, it appears, is true of wild seabirds that can commute hundreds of kilometres a day to find food, according to a recent paper by scientists from McGill and Colgate universities published in the Journal of Experimental Biology.

The researchers studied a colony of small gulls, known as black-legged kittiwakes, that breed and nest in an abandoned radar tower on Middleton Island, Alaska. They attached GPS-accelerometers--Fitbit for birds -- ...

Warming ocean waters could reduce the ability of fish, especially large ones, to extract the oxygen they need from their environment. Animals require oxygen to generate energy for movement, growth and reproduction. In a recent paper in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Science, an international team of researchers from McGill, Montana and Radboud universities describe their newly developed model to determine how water temperature, oxygen availability, body size and activity affect metabolic demand for oxygen in fish.

The model is based on physicochemical principles that look at oxygen consumption and diffusion at the gill surface in relation to water temperature and body size. Predictions were compared against actual measurements from over 200 fish species where oxygen ...

A McGill-led research team has identified a new species of praying mantis thanks to imprints of its fossilized wings. It lived in Labrador, in the Canadian Subarctic around 100 million years ago, during the time of the dinosaurs, in the Late Cretaceous period. The researchers believe that the fossils of the new genus and species, Labradormantis guilbaulti, helps to establish evolutionary relationships between previously known species and advances the scientific understanding of the evolution of the most 'primitive' modern praying mantises. The unusual find, described in a recently published study in Systematic ...

A recent McGill study published in Environmental Science and Technology finds that annual methane emissions from abandoned oil and gas (AOG) wells in Canada and the US have been greatly underestimated - by as much as 150% in Canada, and by 20% in the US. Indeed, the research suggests that methane gas emissions from AOG wells are currently the 10th and 11th largest sources of anthropogenic methane emission in the US and Canada, respectively. Since methane gas is a more important contributor to global warming than carbon dioxide, especially over the short term, the researchers believe that it is essential to gain a clearer understanding of methane ...