(Press-News.org) Various software packages can be used to evaluate products and predict failure; however, these packages are extremely computationally intensive and take a significant amount of time to produce a solution. Quicker solutions mean less accurate results.

To combat this issue, a team of Penn State researchers studied the use of machine learning and image colorization algorithms to ease computational load, maintain accuracy, reduce time and predict strain fields for porous materials. They published their work in the Journal of Computational Materials Science with accompanying presentations and proceedings in Procedia Engineering.

"There is always a human side to design," said Chris McComb, assistant professor of engineering design in the School of Engineering Design, Technology, and Professional Programs. "There are potentially life-saving products that require additive manufacturing and can be frustrating to design. These simulations and evaluations take a long time, so it's important for us to help make it faster and easier to deliver safe products."

The authors include Pranav Milind Khanolkar, a spring 2020 industrial engineering master's alumnus; Aaron Abraham, industrial engineering undergraduate student; Saurabh Basu, assistant professor of industrial engineering; and McComb.

As part of his master's degree, Khanolkar investigated the use of ABAQUS, a widely used software for performing detailed simulations in additive manufacturing. According to the researchers, the software can be problematic because its speed and performance level rely on a computer's hardware processing power.

To speed up the simulations, the team implemented machine learning algorithms to reduce the exclusive use of computationally demanding finite element analysis (FEA). Explained by ABAQUS, FEA can predict crack, impact and crash events with material failure, as well as the dynamics, controls and joint behavior of a product.

Machine learning algorithms can be used to predict mechanical properties and material parameters, which is swift and uses less computational power than traditional FEA.

Khanolkar and Abraham used ABAQUS to perform high-quality FEA over hundreds of hours of work and thousands of data samples on simulated, structurally flawed mechanical parts. They then used these data samples to train machine learning algorithms to estimate the FEA results and maintain high accuracy in only a fraction of the time.

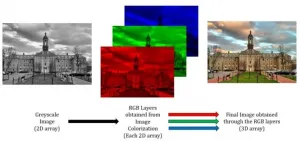

The team applied image colorization algorithms to material microstructure data, and repurposed algorithms that are typically used to add color to black-and-white photos.

In the original case, the algorithms take a black-and-white photo and return the red, green and blue channels for a new, colored version. In the team's work, the algorithm takes a simple image of the material microstructure and returns channels representing different types of potential failures in the product.

"Volumetric defects can affect the performance of a component in several ways, so it's key to understand this effect during the design process of a component," Basu said. "When defects may be unavoidable, like in additively manufactured components, this understanding can help decide how a design may be altered to make the presence of defects tolerable. This can be done by running different design scenarios and ultimately altering the design to achieve a more structurally responsible part. The insights resulting from our study are a first step toward such a framework."

For Khanolkar, the work helped him deeply understand machine learning techniques, providing direction for his current doctoral studies in mechanical and industrial engineering at the University of Toronto.

"Using intelligent technology to help people and empower their creativity and empathy during the design process is important," Khanolkar said. "These algorithms need lots of computational power and using artificial intelligence in this paper allows designers to be more creative without impacting production cost."

INFORMATION:

ITHACA, N.Y. - When humans first domesticated maize some 9,000 years ago, those early breeding efforts led to an increase in harmful mutations to the crop's genome compared to their wild relatives, which more recent modern breeding has helped to correct.

A new comparative study investigates whether the same patterns found in maize occurred in sorghum, a gluten-free grain grown for both livestock and human consumption. The researchers were surprised to find the opposite is true: Harmful mutations in sorghum landraces (early domesticated crops) actually decreased compared to their wild relatives.

The ...

Harbor porpoises have rebounded in a big way off California. Their populations have recovered dramatically since the end of state set-gillnet fisheries that years ago entangled and killed them in the nearshore waters they frequent. These coastal set-gillnet fisheries are distinct from federally-managed offshore drift-gillnet fisheries. They have been prohibited in inshore state waters for more than a decade. The new research indicates that the coastal set gillnets had taken a greater toll on harbor porpoise than previously realized.

The return of harbor porpoises reflects the first documented example of the species rebounding. It's a bright spot for marine wildlife, the scientists write in a new assessment published in Marine Mammal Science.

"This is ...

A new study shows that humans express a powerful hormone during exercise and that treating mice with the hormone improves physical performance, capacity and fitness. Researchers say the findings present new possibilities for addressing age-related physical decline.

The research, published on Wednesday in Nature Communications, reveals a detailed look at how the mitochondrial genome encodes instructions for regulating physical capacity, performance and metabolism during aging and may be able to increase healthy lifespan.

"Mitochondria are known as the cell's energy source, but they are also hubs that coordinate and fine-tune metabolism by actively communicating to the rest of the body," said Changhan David Lee, assistant professor at the USC Leonard Davis School of Gerontology ...

BOSTON - Opioid addiction is persistently stigmatized, delaying and preventing treatment for many - an urgent problem with overdose deaths continuing to rise. To help alleviate this, various medical ways of describing opioid-related impairment, such as "a chronically relapsing brain disease," "illness," or "disorder," have been promoted in diagnostic systems and among national health agencies.

"While intensely debated, there were no rigorous scientific studies out there to inform practice and policy about which terms may be most helpful in reducing stigma," says John F. Kelly, PhD, lead investigator ...

Two novel techniques, atomic-resolution real-time video and conical carbon nanotube confinement, allow researchers to view never-before-seen details about crystal formation. The observations confirm theoretical predictions about how salt crystals form and could inform general theories about the way in which crystal formation produces different ordered structures from an otherwise disordered chemical mixture.

Crystals include many familiar things, such as snowflakes, salt grains and even diamonds. They are regular and repeating arrangements of constituent molecules that grow from a chaotic sea of those molecules. ...

Researchers from King's College London have shown that whole body magnetic resonance imaging (WBMRI) not only detects more myeloma-defining disease than positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT) with 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) but that it also allows critical treatment to be initiated earlier.

In a study published today in the European Journal of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging, researchers looked at 46 patients with suspected myeloma, a debilitating bone marrow cancer which sees 140,000 new cases each year globally.

Less than 50 percent of patients survive after five years and at present it is not clear which is the best imaging ...

"Such reactions are usually carried out using transition metals, such as nickel or iridium," explains Prof. Robert Kretschmer, Junior Professor of Inorganic Chemistry at the University of Jena, whose work has been published in the prestigious Journal of the American Chemical Society. "However, transition metals are expensive and harmful to the environment, both when they are mined and when they are used. Therefore, we are trying to find better alternatives." That two metals can do more than one is already known in the case of transition metals. "However, there has been hardly ...

Viral respiratory diseases are easily transmissible and can spread rapidly across the globe, causing significant damage. The ongoing covid-19 pandemic is a testament to this. In the past too, other viruses have caused massive respiratory disease outbreaks: for example, a subtype of the influenza virus, the type A H1N1 virus, was responsible for the Spanish flu and the Swine flu outbreaks. Thus, to prevent such health crises in the future, timely and accurate diagnosis of these viruses is crucial. This is exactly what researchers from Korea have attempted to work toward, in their brand-new study. Read on to understand how!

For several decades now, polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based assays have been the gold standard for detecting influenza viruses. And while these ...

An international study coordinated by the Research Group for Urban Nature and Biosystems Engineering (NATURIB) from the University of Seville's School of Agricultural Engineering emphasises that having plants at home had a positive influence on the psychological well-being of the dwelling's inhabitants during COVID-19 lockdown. Researchers from the Hellenic Mediterranean University (Greece), the Federal Rural University of Pernambuco (Brazil) and the University of Genoa (Italy) participated in the study along with representatives from the University ...

Did you know that fleas, ants, and click beetles are capable of blazingly fast accelerations, with some up to 10^6 meters per square-second? Their quick movements make fast animals like the cheetah look like slowpokes.

A new study by a team that included Jake Socha, professor in biomedical engineering and mechanics in Virginia Tech's College of Engineering, published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academies of Sciences shows that a snap-through unbending movement of the body is the main reason for the clicking beetle's fast acceleration.

Most animals use muscle to move. For example, when we want to bend our elbow, our biceps ...