(Press-News.org) TAMPA, Fla. -- Evolution within groups of tumor cells follows the principles of natural selection, as evolution in pathogenic microbes. That is, the diversity of cellular characteristics within a group leads to differences in the ability of cells to survive and divide, which leads to selection for cells that bear characteristics that are most fit to the malignant environment. The ability to continuously create a diverse set of new cellular features enables cancers to develop the ability to grow in new tissue environments and to acquire resistance to anti-cancer drugs. The diversity of cell characteristics within groups of cancer cells can be created by a number of well-characterized mechanisms, including small-scale mutations, large-scale genomic changes involving losses, gains and reshuffling of large pieces of DNA, as well as by nongenetic mechanisms that create lasting changes in cellular features. At the same time, scientists generally believe that cancers lack a powerful and important diversification mechanism available to pathogenic microbes, parasexual recombination, or the ability to exchange and recombine genetic material between different cells. However, in a new article published in Nature Ecology & Evolution, Moffitt Cancer Center researchers demonstrate that this belief is wrong and that cancer cells are capable of exchanging and recombining their genetic material with each other through a mechanism mediated by cell fusions.

Why is parasexual recombination important? In its absence, inheritance of genetic information is strictly clonal. As cells divide, the daughter cells inherit the same genetic makeup as their parents, with few modifications due to mutations that accompany cell division. However, many of the features that can give a cell a competitive fitness advantage result from the combined effects of multiple mutations that are not necessarily useful on their own. All of the mutations required for the manifestation of the cell feature need to accumulate in the same cell before their combination can be amplified by selection. Moreover, as many of the random mutational changes are disadvantageous, mutational burden can decrease cellular fitness over time. Exchange and reshuffling of genetic material through parasexual recombination enables groups of cells to explore combination of mutations that accumulated in different clonal lineages, discovering useful combinations of otherwise inconsequential mutations, while also separating useful mutations from disadvantageous ones. As a result, parasexual recombination can enable groups of cells to adapt to new environments more quickly, while avoiding degeneration.

Spontaneous cell fusions involving cancer cells have been described by many groups before. However, most researchers focused on fusions between cancer and noncancer, where cancer cells could acquire important cell characteristics of their nonmalignant fusion partner cells, such as an increased ability to move and migrate to other locations, thus giving these hybrid cancer cells an immediate and specific advantage. Another important line of research suggested that virus-caused fusions between two noncancerous cells can lead to a cancer initiation event. However, since spontaneous cell fusions are relatively uncommon, and because hybrid cells formed by fusion of two cancerous cells do not have an immediately obvious advantage over their nonhybrid peers, fusions between cancer cells have been mostly ignored as rare, inconsequential oddities.

However, interest in cancer evolution and the relatively recent discovery of remarkable genetic diversity within the same tumors motivated Moffitt researchers to take a closer look at consequences of fusions between genetically different cancer cells. They started by asking how frequently cancer cells fuse with each other, labelling cancer cells with either red or green fluorescent markers and counting cells that contained both. While these double positive cells were relatively rare, their presence was documented in most of the multiple cancer cell lines that researchers examined. Importantly, viable double positive cells were also observed in experimental tumors, formed by implantation of tumor cells carrying individual markers. While, on average, these hybrid cells were initially less fit than their normal counterparts, they quickly caught up or even exceeded the ability of their parents to divide and move.

Next, the researchers asked what happens to the genomes of the hybrid cells. Initially, cell fusions give rise to cells that combine all of the DNA information from both of the parents. However, instead of retaining genomes within parent-specific chromosomes, the hybrids appeared to recombine them; as the hybrid cells divided, they were randomly losing some of the extra DNA content. This recombination, and an apparently random loss of extra DNA produced remarkable diversification, where the same hybrid cell gave rise to genetically different daughters. These observations were remarkably similar to a mechanism of parasexual recombination, previously reported for some species of pathogenic yeast.

Finally, Moffitt researchers used computer simulations to compare the ability of groups of cancer cells to evolve with and without fusion-mediated recombination, using quantitative parameters observed in the experimental studies. They found that even with low experimentally observed fusion rates, computer simulation populations were evolving much faster in the presence of cell fusion. The impact of cell fusions was strongest in the modelled cancers with highest mutation rates, as fusion mediated recombination amplified diversity created by mutational mechanisms.

The relevance of these findings toward evolution in actual patient tumors still needs to be rigorously examined. Since all cells within a patient originally start from the same genome, there are no markers to discriminate between mutations that originally occurred within the same or different clonal lineages, which makes the task very challenging. Still, occurrence of genetic recombination between donor and recipient genomes was described in case reports of rare new cancers that developed in patients that underwent bone marrow transplantation.

"Given these studies documenting spontaneous cell fusions in human malignancies, we postulate that our results warrant the suspension of the notion that cancer are strictly asexual and may warrant additional testing of the clinical relevance of spontaneous cell fusions," explained Andriy Marusyk, Ph.D., associate member of the Cancer Physiology Department at Moffitt.

This study reflects a unique culture of multidisciplinary collaboration within Moffitt. The work was co-authored by researchers from the Cancer Physiology and Integrated Mathematical Oncology departments with critical contributions from members of the Biostatistics and Bioinformatics and Pathology departments.

INFORMATION:

The work was supported by the National Cancer Institute (P30-CA076292, U01-CA244101, U01-CA202958), Susan G. Komen (CCR17481976), American Cancer Society, Florida's Bankhead-Coley Cancer Research Program (20B06) and pilot grants from Moffitt's Cancer Biology and Evolution Program and Integrated Mathematical Oncology Workshop.

About Moffitt Cancer Center

Moffitt is dedicated to one lifesaving mission: to contribute to the prevention and cure of cancer. The Tampa-based facility is one of only 51 National Cancer Institute-designated Comprehensive Cancer Centers, a distinction that recognizes Moffitt's scientific excellence, multidisciplinary research, and robust training and education. Moffitt is the No. 11 cancer hospital and has been nationally ranked by U.S. News & World Report since 1999. Moffitt's expert nursing staff is recognized by the American Nurses Credentialing Center with Magnet® status, its highest distinction. With more than 7,000 team members, Moffitt has an economic impact in the state of $2.4 billion. For more information, call 1-888-MOFFITT (1-888-663-3488), visit MOFFITT.org, and follow the momentum on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and YouTube.

European eels spawn in the subtropical Sargasso Sea but spend most of their adult life in a range of fresh- and brackish waters, across Europe and Northern Africa. How eels adapt to such diverse environments has long puzzled biologists. Using whole-genome analysis, a team of scientists led from Uppsala University provides conclusive evidence that all European eels belong to a single panmictic population irrespective of where they spend their adult life, an extraordinary finding for a species living under such variable environmental conditions. The study is published in PNAS, the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

How species adapt to the environment is of fundamental importance in biology. Genetic changes that facilitate survival in individuals occupying new or variable environments ...

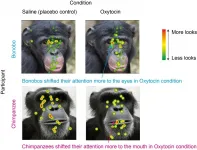

Japan -- Despite being our two closest relatives -- separated by just two million years of evolution from one another and six million from us -- chimpanzees, bonobos, and humans have numerous important differences, such as in lethal aggression demonstrated by chimpanzee males and the high social status of bonobo females.

Now a research study suggests that the hormone oxytocin may have played a central role in this evolutionary divergence.

"Oxytocin is a hormone neuropeptide found in mammals," explains author James Brooks, "but despite its ancient origins, its role can vary even among closely-related species." Among these roles are a wide array of social behaviors, some of which have recently been associated with certain species-typical behaviors in great apes.

Based on these behavioral ...

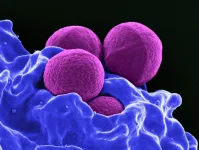

Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) ranks among the globally most important causes of infections in humans and is considered a dreaded hospital pathogen. Active and passive immunisation against multi-resistant strains is seen as a potentially valuable alternative to antibiotic therapy. However, all vaccine candidates so far have been clinically unsuccessful. With an epitope-based immunisation, scientists at Cologne University Hospital and the German Center for Infection Research (DZIF) have now described a new vaccination strategy against S. aureus in the Nature Partner Journal NPJ VACCINES.

S. aureus causes life-threatening conditions such as deep wound infections, sepsis, endocarditis, ...

PITTSBURGH--A smile that lifts the cheeks and crinkles the eyes is thought by many to be truly genuine. But new research at Carnegie Mellon University casts doubt on whether this joyful facial expression necessarily tells others how a person really feels inside.

In fact, these "smiling eye" smiles, called Duchenne smiles, seem to be related to smile intensity, rather than acting as an indicator of whether a person is happy or not, said Jeffrey Girard, a former post-doctoral researcher at CMU's Language Technologies Institute.

"I do think it's possible that we might ...

An international research team has developed a fast and affordable quantum random number generator. The device created by scientists from NUST MISIS, Russian Quantum Center, University of Oxford, Goldsmiths, University of London and Freie Universität Berlin produces randomness at a rate of 8.05 gigabits per second, which makes it the fastest random number generator of its kind. The study published in Physical Review X is a promising starting point for the development of commercial random number generators for cryptography and complex systems modeling.

INFORMATION: ...

ATHENS, Ohio (Jan. 20, 2021) - While the world awaits broad distribution of COVID-19 vaccines, researchers at Ohio University just published highly significant and timely results in the search for another way to stop the virus -- by disrupting its RNA and its ability to reproduce.

Dr. Jennifer Hines, a professor in the Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, along with graduate and undergraduate students in her lab, published the first structural biology analysis of a section of the COVID-19 viral RNA called the stem-loop II motif. This is a non-coding section of the RNA, which means that it is not translated into a protein, but it is likely key to the ...

LEXINGTON, Ky. (January 20, 2021) - More than 5.7 million Americans live with Alzheimer's disease and that number is projected to triple by 2050. Despite the growing number there is not a cure. Florin Despa a professor with the University of Kentucky's department of pharmacology and nutritional sciences says, "The mechanisms underlying neurodegenerative diseases are largely unknown and effective therapies are lacking." That is why numerous studies and trials are ongoing around the world including at the University of Kentucky. One of those studies by University of Kentucky researchers was recently published in Alzheimer's & Dementia: Translational Research & Clinical Interventions. It is the ...

Older adults are managing the stress of the coronavirus pandemic better than younger adults, reporting less depression and anxiety despite also experiencing greater general concern about COVID-19, according to a study recently published by researchers at the UConn School of Nursing.

Their somewhat paradoxical findings, published last month in the journal Aging and Mental Health, suggest that although greater psychological distress has been reported during the pandemic, older age may offer a buffer against negative feelings brought on by the virus's impact.

"When you think about older adulthood, oftentimes, there are downsides. For example, with regard to physical well-being, we don't recover as well from injury or ...

Not long after the sun goes down, pairs of burying beetles, or Nicrophorus orbicollis, begin looking for corpses.

For these beetles, this is not some macabre activity; it's house-hunting, and they are in search of the perfect corpse to start a family in. They can sense a good find from miles away, because carrion serves as a food source for countless members of nature's clean-up crew. But because these beetles want to live in these corpses, they don't want to share their discovery. As a result, burying beetles have clever ways of claiming their decaying prize all for themselves. In new research published in The American Naturalist, researchers from UConn and The University of Bayreuth have found these beetles recruit microbes to help throw rivals off the scent.

Immediately following ...

The NFL playoffs are underway, and fans are finding ways to simulate tailgating during the COVID-19 pandemic. Football watch parties are synonymous with eating fatty foods and drinking alcohol. Have you ever wondered what all of that eating and drinking does to your body?

Researchers from the University of Missouri School of Medicine simulated a tailgating situation with a small group of overweight but healthy men and examined the impact of the eating and drinking on their livers using blood tests and a liver scan. They discovered remarkably differing responses in the subjects.

"Surprisingly, we found that in overweight men, after an afternoon of eating and drinking, how their bodies reacted to food and drink was not uniform," said Elizabeth Parks, PhD, professor of nutrition and ...