How the brain learns that earmuffs are not valuable at the beach

Researchers at the University of Tsukuba in Japan and the NEI in the USA have discovered a circuit in the basal ganglia of the brain that allows monkeys to learn context-dependent object worth

2021-01-21

(Press-News.org) Tsukuba, Japan -- How valuable are earmuffs? The answer to this simple question can depend. What brand are they? Are they good quality? What is the weather like? Given the choice between earmuffs and suntan lotion, most people would choose to have the earmuffs on a cold winter day and the lotion on a sunny day at the beach. This ability to place different values on objects depending on the environmental context is something that we do all the time without much thought or effort. But how does it work? A new study led by Assistant Professor Jun Kunimatsu at the University of Tsukuba in Japan and Distinguished Investigator Okihide Hikosaka at the National Eye Institute (NEI) in the United States has discovered the part of the brain that allows this type of learning to occur.

"Value and reward are known to be encoded in the part of the brain called the basal ganglia," explains Dr. Hikosaka. "We set out to identify the specific neuronal circuits underlying environment-based value learning."

To find the answer, the researchers first taught monkeys a kind of "Where's Waldo" game in which they searched scenes for embedded objects that gave them rewards. Looking at the objects could lead big or small rewards depending on the background scene in which they were embedded. After the monkeys learned this game using many objects and many backgrounds, they were able to routinely make eye movements to the big rewards and avoid looking at the small rewards, even when the background scenes were switched suddenly.

The final output from the basal ganglia controls motor movements, in this case eye movements. The team hypothesized that a certain kind of brain cell called fast-spiking neurons were responsible for the successful learning of their game. To test this idea, they used a drug to temporarily block input from these cells to different parts of the basal ganglia just when monkeys were trying to learn the associations between objects, backgrounds, and values. They found that when input to the tail end of the striatum--a part of the basal ganglia-- was blocked, it prevented monkeys from learning new scene-based associations, but did not prevent them from performing well when they were given scenes and objects that they had already learned.

The findings could have applications in clinical research. "Reduced input from fast-spiking neurons has been observed in some clinical conditions," says Dr. Kunimatsu, "including Tourette syndrome and Huntington's disease, both of which are accompanied by deficits in skill learning that could be related to an inability to learn environment-based values."

INFORMATION:

The article, "Environment-based object values learned by local network in the striatum tail," was published in PNAS at DOI: https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2013623118.

[Attachments] See images for this press release:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-01-21

The elusive axion particle is many times lighter than an electron, with properties that barely make an impression on ordinary matter. As such, the ghost-like particle is a leading contender as a component of dark matter -- a hypothetical, invisible type of matter that is thought to make up 85 percent of the mass in the universe.

Axions have so far evaded detection. Physicists predict that if they do exist, they must be produced within extreme environments, such as the cores of stars at the precipice of a supernova. When these stars spew axions out into the universe, the ...

2021-01-21

Tsukuba, Japan - A team of researchers from the Faculty of Pure and Applied Sciences at the University of Tsukuba filmed the ultrafast motion of electrons with sub-nanoscale spatial resolution. This work provides a powerful tool for studying the operation of semiconductor devices, which can lead to more efficient electronic devices.

The ability to construct ever smaller and faster smartphones and computer chips depends on the ability of semiconductor manufacturers to understand how the electrons that carry information are affected by defects. However, these motions occur on the scale of trillionths of a second, and they can only be seen with a microscope that can image individual atoms. ...

2021-01-21

The results of a study led by Northern Arizona University and the Translational Genomics Research Institute (TGen), an affiliate of City of Hope, suggest the immune systems of people infected with COVID-19 may rely on antibodies created during infections from earlier coronaviruses to help fight the disease.

COVID-19 isn't humanity's first encounter with a coronavirus, so named because of the corona, or crown-like, protein spikes on their surface. Before SARS-CoV-2 -- the virus that causes COVID-19 -- humans have navigated at least 6 other types of coronaviruses.

The study sought to understand how coronaviruses (CoVs) ignite the human immune system and conduct a deeper ...

2021-01-21

An adverse upbringing often impairs people's circumstances and health in their adult years, especially for couples who have both had similar experiences. This is shown by a new study, carried out by Uppsala University researchers, in which 818 mothers and their partners filled in a questionnaire one year after having a child together. The study is now published in the scientific journal PLOS ONE.

"When we studied couples where both partners stated they'd had a hard time as children, the connection between negative childhood experience and a relatively ...

2021-01-21

Early Medieval Europe is frequently viewed as a time of cultural stagnation, often given the misnomer of the 'Dark Ages'. However, analysis has revealed new ideas could spread rapidly as communities were interconnected, creating a surprisingly unified culture in Europe.

Dr Emma Brownlee, Department of Archaeology, University of Cambridge, examined how a key change in Western European burial practices spread across the continent faster than previously believed - between the 6th - 8th centuries AD, burying people with regionally specific grave goods was largely abandoned in favour of a more standardised, unfurnished burial.

"Almost everyone from the eighth century onwards ...

2021-01-21

As scientists increasingly rely on eyewitness accounts of earthquake shaking reported through online systems, they should consider whether those accounts are societally and spatially representative for an event, according to a new paper published in Seismological Research Letters.

Socioeconomic factors can play a significant if complex role in limiting who uses systems such as the U.S. Geological Survey's "Did You Feel It?" (DYFI) to report earthquake shaking. In California, for instance, researchers concluded that DYFI appears to gather data across a wide socioeconomic range, albeit with some intriguing differences related to neighborhood income levels during earthquakes such as the ...

2021-01-21

The neocortex is the part of the brain that humans use to process sensory impressions, store memories, give instructions to the muscles, and plan for the future. These computational processes are possible because each nerve cell is a highly complex miniature computer that communicates with around 10,000 other neurons. This communication happens via special connections called synapses.

The bigger the synapse, the stronger its signal

Researchers in Kevan Martin's laboratory at the Institute of Neuroinformatics at the University of Zurich (UZH) and ETH Zurich have now shown for the first time that the size of synapses determines the strength of their ...

2021-01-21

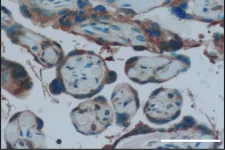

TAMPA, Fla. -- Myelodysplastic Syndromes (MDS) and acute myeloid leukemia (AML) are rare hematologic malignancies of the bone marrow. They can occur spontaneously or secondary to treatment for other cancers, so called therapy related disease, which is frequently associated with a mutation of the tumor suppressor gene TP53. Standard treatment for these patients includes hypomethylating agents such as azacitidine or decitabine but unfortunately outcomes are very poor.

"Patients with TP53-mutant disease, which is roughly 10% to 20% of AML and de novo MDS cases, don't have many options ...

2021-01-21

Growing perennial grasses on abandoned cropland has the potential to counteract some of the negative impacts of climate change by switching to more biofuels, according to a research group from the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU).

Researchers consider increased use of biofuels to be an important part of the solution to reduce CO2 emissions. But the production of plants for biofuels can have some unfortunate trade-offs.

Now, the NTNU researchers have come up with a scenario that would put less pressure on food production and plant and animal life.

"We can grow perennial grasses in areas that until recently were used for growing food but that are no longer used for that purpose," explains Jan Sandstad ...

2021-01-21

DURHAM, N.C. - Researchers at Duke and Mt. Sinai have identified a molecular mechanism that prevents a viral infection during a mother's pregnancy from harming her unborn baby.

When a person becomes infected by a virus, their immune system sends out a chemical signal called type I interferon, which tells surrounding cells to increase their anti-viral defenses, including making more inflammation.

This response helps to prevent the virus from copying itself and gives the adaptive immune system more time to learn about the new invader and begin to hunt it down.

A pregnant woman ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] How the brain learns that earmuffs are not valuable at the beach

Researchers at the University of Tsukuba in Japan and the NEI in the USA have discovered a circuit in the basal ganglia of the brain that allows monkeys to learn context-dependent object worth