(Press-News.org) Once regarded as merely cast-off waste products of cellular life, bacterial membrane vesicles (MVs) have since become an exciting new avenue of research, due to the wealth of biological information they carry to other bacteria as well as other cell types.

These tiny particles, produced by most bacteria, can bud off from outer cellular membranes, traveling along cell surfaces and occasionally migrating into intercellular spaces.Luis Cisneros is a researcher in the Biodesign Center for Biocomputing, Security and Society, and the BEYOND Center for Fundamental Concepts in Science, at Arizona state University.

In a new study, Luis H. Cisneros and his colleagues describe the effects of antibiotics on membrane vesicles, demonstrating that such drugs actively modify the properties of vesicle transport. Under the influence of antibiotics, MVs were produced and released by bacteria in greater abundance and traveled faster and further from their origin.

The researchers suggest that the altered behaviors of MVs may represent a stress response to the presence of antibiotics and further, that MVs liberated from the cell membrane may transmit urgent warning signals to neighboring cells and perhaps foster antibiotic resistance.

"It's long been believed that membrane vesicles are involved in the cell-cell signaling process leading to changes in the collective behavior of living cells, like the coordination of survival responses due to antibiotic stress," Cisneros says. "But many details in the dynamics of this process are not yet well understood. Our work opens a new door in this field."

Cisneros is a researcher in the Biodesign Center for Biocomputing, Security and Society, and the BEYOND Center for Fundamental Concepts in Science, at Arizona state University. He is joined by Julia Bos and Didier Mazel, colleagues from the Institut Pasteur, Paris.

The research finding appear in the current issue of the journal Science Advances.

Bacterial satellites

Membrane vesicles--encapsulated particles shed from the membranes of bacteria-- are conduits of information. Like nanoscale flash drives, they can encode and carry volumes of data in the form of polysaccharides, proteins, DNAs, RNAs, metabolites, enzymes, and toxins. They also express many proteins on their outer membrane that are derived from the bacterial surfaces from which they were exuded.

Groundbreaking research on the mechanisms controlling vesicles traffic were awarded a Nobel Prize in Physiology and Medicine in 2013 and are currently being used to package the SPIKE mRNA in the long- awaited COVID-19 vaccine.

The rich storehouse of information carried by MVs and its ultimate effect on bacterial and non-bacterial cells is of great scientific and medical concern. In addition to alerting fellow bacteria of environmental stresses like antibiotics, MVs have been implicated in the quorum sensing activities that inform bacteria of overall population densities and may even affect brain processes in higher mammals. This could occur if MVs produced by gut microbes transport their cargo to the nervous system.

Membrane vesicles are common to all life kingdoms, from bacteria and other unicellular organisms to archaea and eukaryotic cells found in multicellular organisms, including cancer cells. Depending on the cell type from which they emerge, they have been implicated as vital contributors to intercellular communication, coagulation, inflammatory processes and the genesis of tumors as well as playing a role in the biology of stem cells.

A closer look

Despite their importance however, MVs have received inadequate attention until recently. Due to their diminutive nature, measuring between 20 and 400 nm in diameter, they are a challenging subject of study, particularly in their natural state within living systems.

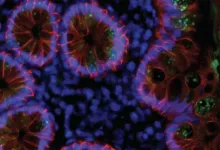

Key to gaining insight into the subtle behavior of MV's has been technological advances that allow them to be closely observed. The new study outlines sophisticated methods of florescence microscopy and data analysis used to track the production and transport of MVs under laboratory scrutiny.

Traditionally, MV's have been studied with the aid of biochemical techniques, electron microscopy, and atomic force microscopy. These methods have helped researchers probe the contents of MVs, which may contain nucleic acids, proteins, lipids, various toxins, antibiotics, phage receptors, signaling molecules, metabolites, metals, and growth factors. The precise composition of MVs is dependent on physiological details of the mother cell as well as the mode by which the MVs are formed.

Likewise, numerous factors can affect the formation and release of MVs. These include antibiotics and chemotherapy drugs, environmental influences, cell death and necrosis as well as damage to the bacterium's DNA. The heightened production and transport of MVs may be a generalized response to bacterial stress.

Bacterial information highway

The downstream effects of MV transport likewise remain a topic of considerable speculation. The release of MVs appears to be involved in a number of critical biological processes including cell-cell communication, horizontal gene transfer, social phenomena and immune response modulation. Importantly, they are also believed to act as decoys for antibiotics.

To better understand these and other attributes of MVs in living systems, it is vital to closely follow their movements over time. The current study represents the first high-resolution, quantitative tracking of MVs in response to antibiotic treatment.

The experiments described involve a population of live Escherichia coli, commensal bacteria common in the human gut. The individual MVs were tagged with a fluorescent dye, then visualized using time-lapse fluorescence microscopy at high magnification combined with fast image acquisition. Additionally, MV transport was investigated with imaging tools allowing particle tracking to be fully automated.

Analysis of vesicle movement revealed that treatment with low doses of antibiotic significantly altered vesicle dynamics, vesicle-to-membrane affinity, and surface properties of the cell membranes, generally enhancing vesicle transport along the surfaces of bacterial membranes. Continuing studies should help researchers determine if populations of bacteria displaying ramped-up, stress-induced MV transport show enhanced antibiotic resistance.

According to Bos, corresponding author of the new study, "this is the first evidence that tracking thousands of individual membrane vesicle trajectories in real-time in a live population of microorganisms has been achieved. Gaining insights into how they move and locate themselves within a bacterial microcolony and how their motion properties could be a signature of antibiotic stress, will undoubtedly open a new avenue of research on this fascinating and currently hot topic."

The study helps advance our understanding of these as-yet mysterious entities while potentially paving the way for a range of applications in immunology and biotechnology.

INFORMATION:

Written by: Richard harth

Senior Science Writer: The Biodesign Institute

richard.harth@asu.edu

DURHAM, N.C. -- Researchers at Duke University have developed a predictive theory for tumor growth that approaches the subject from a new point of view. Rather than focusing on the biological mechanisms of cellular growth, the researchers instead use thermodynamics and the physical space the tumor is expanding into to predict its evolution from a single cell to a complex cancerous mass.

The results appeared Jan. 15 in the journal Biosystems.

"When scientists think about cancer, the first thing that comes to mind is biology, and they tend to overlook the physical reality of ...

Indigenous peoples' lands may harbour a significant proportion of threatened and endangered species globally, according to University of Queensland-led research.

UQ's Dr Chris O'Bryan and his team conducted the first comprehensive analysis of land mammal composition across mapped Indigenous lands.

"These lands cover more than one-quarter of the Earth, of which a significant proportion is still free from industrial-level human impacts," Dr O'Bryan said.

"As a result, Indigenous peoples and their lands are crucial for the long-term persistence of the planet's biodiversity and ecosystem services.

"Despite this, we know relatively little about what animals, including highly imperilled species, may reside in or depend on these lands."

The team overlayed maps of Indigenous ...

ITHACA, N.Y. - Far below the gaseous atmospheric shroud on Saturn's largest moon, Titan, lies Kraken Mare, a sea of liquid methane. Cornell University astronomers have estimated that sea to be at least 1,000-feet deep near its center - enough room for a potential robotic submarine to explore.

After sifting through data from one of the final Titan flybys of the Cassini mission, the researchers detailed their findings in "The Bathymetry of Moray Sinus at Titan's Kraken Mare," which published in the Journal of Geophysical Research.

"The depth and composition of each of Titan's seas had already been measured, ...

University of Illinois Chicago is one of the U.S. sites participating in clinical trials to cure severe red blood congenital diseases such as sickle cell anemia or Thalassemia by safely modifying the DNA of patients' blood cells.

The first cases treated with this approach were recently published in an article co-authored by Dr. Damiano Rondelli, the Michael Reese Professor of Hematology at the UIC College of Medicine. The article reports two patients have been cured of beta thalassemia and sickle cell disease after their own genes were edited with CRISPR-Cas9 technology. The two researchers ...

New research from McMaster University has found that psychiatric help for mothers with postpartum depression results in healthy changes in the brains of their babies.

The study, published in the journal Depression and Anxiety this week, found treating mothers who had postpartum depression with cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) not only helped the moms, but resulted in adaptive changes in the brains and behaviour of their infants.

More specifically, after the mothers' treatment, their infants showed healthy changes in their nervous and cardiovascular systems, and they were observed to better regulate their behaviours and emotions by both mothers and fathers.

"In fact, we found that after their moms were treated that their infant's ...

As the number of people who have fought off SARS-CoV-2 climbs ever higher, a critical question has grown in importance: How long will their immunity to the novel coronavirus last? A new Rockefeller study offers an encouraging answer, suggesting that those who recover from COVID-19 are protected against the virus for at least six months, and likely much longer.

The findings, published in Nature, provide the strongest evidence yet that the immune system "remembers" the virus and, remarkably, continues to improve the quality of antibodies even after the infection has waned. Antibodies produced ...

BIRMINGHAM, Ala. - University of Alabama at Birmingham polymer and radionuclide chemists report what they say "may represent a major step forward in microcapsule drug delivery systems."

The UAB microcapsules -- labeled with radioactive zirconium-89 -- are the first example of hollow polymer capsules capable of long-term, multiday positron emission tomography, or PET, imaging in vivo. In previous work, UAB researchers showed that the hollow capsules could be filled with a potent dose of the cancer drug doxorubicin, which could then be released by therapeutic ultrasound that ruptures the microcapsules.

PET imaging with zirconium-89 -- which has a half-life of 3.3 days -- allowed the capsules to be traced in test mice up to seven days. The major ...

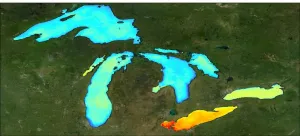

NASA-funded research on the 11 largest freshwater lakes in the world coupled field and satellite observations to provide a new understanding of how large bodies of water fix carbon, as well as how a changing climate and lakes interact.

Scientists at the Michigan Tech Research Institute (MTRI) studied the five Laurentian Great Lakes bordering the U.S. and Canada; the three African Great Lakes, Tanganyika, Victoria and Malawi; Lake Baikal in Russia; and Great Bear and Great Slave lakes in Canada.

These 11 lakes hold more than 50% of the surface freshwater that millions of people and countless other creatures rely on, underscoring the importance of understanding how they are being altered by climate change and other factors.

The two Canadian lakes ...

BUFFALO, N.Y. -- In the dark waters of Lake Superior, a fish species adapted to regain a genetic trait that may have helped its ancient ancestors see in the ocean, a study finds.

The research focuses on kiyis, which inhabit Lake Superior at depths of about 80 to over 200 meters deep. These fish, known to scientists as "Coregonus kiyi," belong to a group of closely related salmonids known as ciscoes.

In contrast to three other Lake Superior ciscoes that dwell and feed in shallower regions of water, the kiyis are far more likely to carry a version of the rhodopsin gene that probably improves vision in dim "blue-shifted" waters, ...

Curtin University researchers have uncovered a method of making silicon, found commonly in electronics such as phones, cameras and computers, at room temperature.

The new technique works by replacing extreme heat with electrical currents to produce the same chemical reaction that turns silica into silicon at a reduced economic and environmental cost.

Lead researcher, PhD candidate Song Zhang from Curtin's School of Molecular and Life Sciences said that while the team's discovery was made at the nanoscale, it defines a way of replacing thermochemical processes with electrochemical processes, which ...