(Press-News.org) When it launches in the mid-2020s, NASA's Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope will explore an expansive range of infrared astrophysics topics. One eagerly anticipated survey will use a gravitational effect called microlensing to reveal thousands of worlds that are similar to the planets in our solar system. Now, a new study shows that the same survey will also unveil more extreme planets and planet-like bodies in the heart of the Milky Way galaxy, thanks to their gravitational tug on the stars they orbit.

"We were thrilled to discover that Roman will be able to offer even more information about the planets throughout our galaxy than originally planned," said Shota Miyazaki, a graduate student at Osaka University in Japan who led the study. "It will be very exciting to learn more about a new, unstudied batch of worlds."

Roman will primarily use the gravitational microlensing detection method to discover exoplanets - planets beyond our solar system. When a massive object, such as a star, crosses in front of a more distant star from our vantage point, light from the farther star will bend as it travels through the curved space-time around the nearer one.

The result is that the closer star acts as a natural lens, magnifying light from the background star. Planets orbiting the lens star can produce a similar effect on a smaller scale, so astronomers aim to detect them by analyzing light from the farther star.

Since this method is sensitive to planets as small as Mars with a wide range of orbits, scientists expect Roman's microlensing survey to unveil analogs of nearly every planet in our solar system. Miyazaki and his colleagues have shown that the survey also has the power to reveal more exotic worlds - giant planets in tiny orbits, known as hot Jupiters, and so-called "failed stars," known as brown dwarfs, which are not massive enough to power themselves by fusion the way stars do.

This new study shows that Roman will be able to detect these objects orbiting the more distant stars in microlensing events, in addition to finding planets orbiting the nearer (lensing) stars.

The team's findings are published in The Astronomical Journal.

Astronomers see a microlensing event as a temporary brightening of the distant star, which peaks when the stars are nearly perfectly aligned. Miyazaki and his team found that in some cases, scientists will also be able to detect a periodic, slight variation in the lensed starlight caused by the motion of planets orbiting the farther star during a microlensing event.

As a planet moves around its host star, it exerts a tiny gravitational tug that shifts the star's position a bit. This can pull the distant star closer and farther from a perfect alignment. Since the nearer star acts as a natural lens, it's like the distant star's light will be pulled slightly in and out of focus by the orbiting planet. By picking out little shudders in the starlight, astronomers will be able to infer the presence of planets.

"It's called the xallarap effect, which is parallax spelled backward. Parallax relies on motion of the observer - Earth moving around the Sun - to produce a change in the alignment between the distant source star, the closer lens star and the observer. Xallarap works the opposite way, modifying the alignment due to the motion of the source," said David Bennett, who leads the gravitational microlensing group at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland.

While microlensing is generally best suited to finding worlds farther from their star than Venus is from the Sun, the xallarap effect works best with very massive planets in small orbits, since they make their host star move the most. Revealing more distant planets will also allow us to probe a different population of worlds.

Mining the core of the galaxy

Most of the first few hundred exoplanets discovered in our galaxy had masses hundreds of times greater than Earth's. Unlike the giant planets in our solar system, which take 12 to 165 years to orbit the Sun, these newfound worlds whirl around their host stars in as little as a few days.

These planets, now known as hot Jupiters due to their giant size and the intense heat from their host stars, weren't expected from existing planetary formation models and forced astronomers to rethink them. Now there are several theories that attempt to explain why hot Jupiters exist, but we still aren't sure which - if any - is correct. Roman's observations should reveal new clues.

Even more massive than hot Jupiters, brown dwarfs range from about 4,000 to 25,000 times Earth's mass. They're too heavy to be characterized as planets, but not quite massive enough to undergo nuclear fusion in their cores like stars.

Other planet-hunting missions have primarily searched for new worlds relatively nearby, up to a few thousand light-years away. Close proximity makes more detailed studies possible. However, astronomers think that studying bodies close to our galaxy's core may yield new insight into how planetary systems evolve. Miyazaki and his team estimate that Roman will find around 10 hot Jupiters and 30 brown dwarfs nearer to the center of the galaxy using the xallarap effect.

The center of the galaxy is populated mainly with stars that formed around 10 billion years ago. Studying planets around such old stars could help us understand whether hot Jupiters form so close to their stars, or are born farther away and migrate inward over time. Astronomers will be able to see if hot Jupiters can maintain such small orbits for long periods of time by seeing how frequently they're found around ancient stars.

Unlike stars in the galaxy's disk, which typically roam the Milky Way at comfortable distances from one another, stars near the core are packed much closer together. Roman could reveal whether having so many stars so close to each other affects orbiting planets. If a star passes close to a planetary system, its gravity could pull planets out of their usual orbits.

Supernovae are also more common near the center of the galaxy. These catastrophic events are so intense that they can forge new elements, which are spewed into the surrounding area as the exploding stars die. Astronomers think this might affect planet formation. Finding worlds in this region could help us understand more about the factors that influence the planet-building process.

Roman will open up a window into the distant past by looking at older stars and planets. The mission will also help us explore whether brown dwarfs form as easily near the center of the galaxy as they do closer to Earth by comparing how frequently they're found in each region.

By tallying up very old hot Jupiters and brown dwarfs using the xallarap effect and finding more familiar worlds using microlensing, Roman will bring us another step closer to understanding our place in the cosmos.

"We've found a lot of planetary systems that seem strange compared with ours, but it's still not clear whether they're the oddballs or we are," said Samson Johnson, a graduate student at Ohio State University in Columbus and a co-author of the paper. "Roman will help us figure it out, while helping answer other big questions in astrophysics."

INFORMATION:

The Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope is managed at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, with participation by NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory and Caltech/IPAC in Pasadena, California, the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore, and a science team comprising scientists from various research institutions. The primary industrial partners are Ball Aerospace and Technologies Corporation in Boulder, Colorado, L3Harris Technologies in Melbourne, Florida, and Teledyne Scientific & Imaging in Thousand Oaks, California.

Hitting a pothole on the road in just the wrong way might create a bulge on the tire, a weakened spot that will almost certainly lead to an eventual flat tire. But what if that tire could immediately begin reknitting its rubber, reinforcing the bulge and preventing it from bursting?

That's exactly what blood vessels can do after an aneurysm forms, according to new research led by the University of Pittsburgh's Swanson School of Engineering and in partnership with the Mayo Clinic. Aneurysms are abnormal bulges in artery walls that can form in brain arteries. Ruptured brain aneurysms are fatal in almost 50% of cases.

The research, recently published in Experimental Mechanics, is the first to show that there are two phases of wall restructuring after an aneurysm forms, the first ...

PHILADELPHIA (January 25, 2021) - While eating less and moving more are the basics of weight control and obesity treatment, finding ways to help people adhere to a weight-loss regimen is more complicated. Understanding what features make a diet easier or more challenging to follow can help optimize and tailor dietary approaches for obesity treatment.

A new paper from the University of Pennsylvania School of Nursing (Penn Nursing) analyzed different dietary approaches and clinical trials to better understand how to optimize adherence and subsequent weight reduction. The findings have been published in the Journal of Clinical Investigation.

"There is not convincing evidence that one diet is universally easier to adhere to than another for extended periods, a feature necessary for long-term ...

Research by an international team of medical experts has found cancer patients could be up to four times more likely to die following cancer surgery in low to lower-middle income countries than in high-income countries. It also revealed lower-income countries are less likely to have post-operative care infrastructure and oncology services.

The global observational study, published in The Lancet, explored global variation in post-operative complications and deaths following surgery for three common cancers. It was conducted by researchers from the GlobalSurg Collaborative and NIHR Global Health Unit on Global Surgery - led by the University of Edinburgh, with analysis and support from the University of Southampton.

Between April 2018 and January 2019, researchers enrolled 15,958 ...

COLUMBUS, Ohio - Older minority cancer patients with poor social determinants of health are significantly more likely to experience negative surgical outcomes compared to white patients with similar risk factors, according to a new study published by researchers at The Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center - Arthur G. James Cancer Hospital and Richard J. Solove Research Institute (OSUCCC - James).

A new retrospective analysis of more than 200,000 patients conducted by researchers with the OSUCCC - James suggests that minority patients living in high socially vulnerable neighborhoods had a 40% increased risk of a complication ...

CHAMPAIGN, Ill. -- Absent a widely available vaccine, mitigation measures such as stay-at-home mandates, lockdowns or shelter-in-place orders have been the major public health policies deployed by state governments to curb the spread of COVID-19.

But given the uncertain duration of such policies, questions have been raised about the potential negative mental health consequences of extended lockdowns with indefinite end dates. But according to new research co-written by a team of University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign experts who study the intersection of health care and public policy, the negative mental health effects of ...

ITHACA, N.Y. - Researchers from Cornell University and the National Park Service have pinpointed and confirmed the location of the remnants of a wooden fort in Alaska - the Tlingit people's last physical bulwark against Russian colonization forces in 1804 - by using geophysical imaging techniques and ground-penetrating radar.

The fort was the last physical barrier to fall before Russia's six-decade occupation of Alaska, which ended when the United States purchased Alaska in 1867 for $7 million.

The Tlingit built what they called Shiskinoow - the "sapling fort" - on a peninsula in modern-day Sitka, Alaska, ...

During epileptic seizures, a large number of nerve cells in the brain fire excessively and in synchrony. This hyperactivity may lead to uncontrolled shaking of the body and involve periods of loss of consciousness. While about two thirds of patients respond to anti-epileptic medication, the remainder is refractory to medical treatment and shows drug-resistance. These patients are in urgent need for new therapeutic strategies.

Together with colleagues in Japan, Prof. Dr. Christine Rose and her doctoral student Jan Meyer from the Institute of Neurobiology at HHU have performed a study to address the cellular mechanisms that promote the development of epilepsy. While up to now, most studies and anti-epileptic drugs targeted nerve cells (neurons), ...

Findings of a new study published by researchers from Trinity College Dublin and St James's Hospital outline the health impacts faced by older people while cocooning during the Covid-19 pandemic. The findings are published in the Quarterly Journal of Medicine here: https://bit.ly/3qGKJoI.

Cocooning involves staying at home and reducing face-to-face interaction with other people and is an important part of the response to the COVID-19 pandemic, with an overall aim to prevent transmission to vulnerable older people. However, concerns exist regarding the long-term adverse effects ...

A new study from Indiana University researchers finds that most high-school age youth are willing to wear masks to help prevent the spread of the COVID-19 virus, but that more education is needed on how to wear masks properly and on the importance of consistent commitment to public health guidelines.

The study, published today in the Journal of Adolescent Health looked at 1,152 youth's mask wearing and social distancing behaviors during five, in-person live-streamed high school graduations from one U.S. public school district in early July 2020. These broadcasts allowed the researchers to systematically document social-distancing behaviors throughout the ceremonies and mask-wearing as students crossed the graduation stage ...

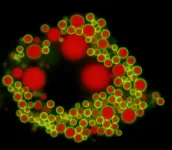

Coconut oil has increasingly found its way into German kitchens in recent years, although its alleged health benefits are controversial. Scientists at the University of Bonn have now been able to show how it is metabolized in the liver. Their findings could also have implications for the treatment of certain diarrheal diseases. The results are published in the journal Molecular Metabolism.

Coconut oil differs from rapeseed or olive oil in the fatty acids it contains. Fatty acids consist of carbon atoms bonded together, usually 18 in number. In coconut oil, however, most of these chains are much shorter and contain only ...