(Press-News.org) Tracking milk drinking in the ancient past is not straightforward. For decades, archaeologists have tried to reconstruct the practice by various indirect methods. They have looked at ancient rock art to identify scenes of animals being milked and at animal bones to reconstruct kill-off patterns that might reflect the use of animals for dairying. More recently, they even used scientific methods to detect traces of dairy fats on ancient pots. But none of these methods can say if a specific individual consumed milk.

Now archaeological scientists are increasingly using proteomics to study ancient dairying. By extracting tiny bits of preserved proteins from ancient materials, researchers can detect proteins specific to milk, and even specific to the milk of particular species.

Where are these proteins preserved? One critical reservoir is dental calculus - dental plaque that has mineralized and hardened over time. Without toothbrushes, many ancient people couldn't remove plaque from their teeth, and so developed a lot of calculus. This may have led to tooth decay and pain for our ancestors but it also produced a goldmine of information about ancient diets, with plaque often trapping food proteins and preserving them for thousands of years.

Now, an international team led by researchers at the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History in Jena, Germany and the National Museums of Kenya (NMK) in Nairobi, Kenya have analyzed some of the most challenging ancient dental calculus to date. Their new study, published in Nature Communications, examines calculus from human remains in Africa, where high temperatures and humidity were thought to interfere with protein preservation.

The team analyzed dental calculus from 41 adult individuals from 13 ancient pastoralist sites excavated in Sudan and Kenya and, remarkably, retrieved milk proteins from 8 of the individuals.

The positive results were greeted with enthusiasm by the team. As lead author Madeleine Bleasdale observes, "some of the proteins were so well preserved, it was possible to determine what species of animal the milk had come from. And some of the dairy proteins were many thousands of years old, pointing to a long history of milk drinking in the continent."

The earliest milk proteins reported in the study were identified at Kadruka 21, a cemetery site in Sudan dating to roughly 6,000 years ago. In the calculus of another individual from the adjacent cemetery of Kadruka 1, dated to roughly 4,000 years ago, researchers were able to identify species-specific proteins and found that the source of the dairy had been goat's milk.

"This the earliest direct evidence to date for the consumption of goat's milk in Africa," says Bleasdale. "It's likely goats and sheep were important sources of milk for early herding communities in more arid environments."

The team also discovered milk proteins in dental calculus from an individual from Lukenya Hill, an early herder site in southern Kenya dated to between 3,600 and 3,200 years ago.

"It seems that animal milk consumption was potentially a key part of what enabled the success and long-term resilience of African pastoralists," observes coauthor Steven Goldstein.

As research on ancient dairying intensifies around the world, Africa remains an exciting place to examine the origins of milk drinking. The unique evolution of lactase persistence in Africa, combined with the fact that animal milk consumption remains critical to many communities across the continent, makes it vital for understanding how genes and culture can evolve together.

Normally, lactase - an enzyme critical for enabling the body to fully digest milk - disappears after childhood, making it much more difficult for adults to drink milk without discomfort. But in some people, lactase production persists into adulthood - in other words these individuals have 'lactase persistence.'

In Europeans, there is one main mutation linked to lactase persistence, but in different populations across Africa, there are as many as four. How did this come to be? The question has fascinated researchers for decades. How dairying and human biology co-evolved has remained largely mysterious despite decades of research.

By combining their findings about which ancient individuals drank milk with genetic data obtained from some of the ancient African individuals, the researchers were also able to determine whether early milk drinkers on the continent were lactase persistent. The answer was no. People were consuming dairy products without the genetic adaptation that supports milk drinking into adulthood.

This suggests that drinking milk actually created the conditions that favoured the emergence and spread of lactase persistence in African populations. As senior author and Max Planck Director Nicole Boivin notes, "This is a wonderful example of how human culture has - over thousands of years - reshaped human biology."

But how did people in Africa drink milk without the enzyme needed to digest it? The answer may lie in fermentation. Dairy products like yogurt have a lower lactose content than fresh milk, and so early herders may have processed milk into dairy products that were easier to digest.

Critical to the success of the research was the Max Planck scientists' close partnership with African colleagues, including those at the National Corporation of Antiquities and Museums (NCAM), Sudan, and long-term collaborators at the National Museums of Kenya (NMK). "It's great to get a glimpse of Africa's important place in the history of dairying," observes coauthor Emmanuel Ndiema of the NMK. "And it was wonderful to tap the rich potential of archaeological material excavated decades ago, before these new methods were even invented. It demonstrates the ongoing value and importance of museum collections around the world, including in Africa."

INFORMATION:

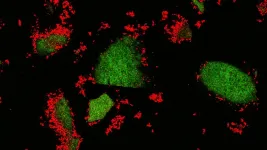

CHAMPAIGN, Ill. -- Researchers used single-molecule imaging to compare the genome-editing tools CRISPR-Cas9 and TALEN. Their experiments revealed that TALEN is up to five times more efficient than CRISPR-Cas9 in parts of the genome, called heterochromatin, that are densely packed. Fragile X syndrome, sickle cell anemia, beta-thalassemia and other diseases are the result of genetic defects in the heterochromatin.

The researchers report their findings in the journal Nature Communications.

The study adds to the evidence that a broader selection of genome-editing tools is needed to target all parts of the genome, said Huimin Zhao, a professor of chemical and biomolecular engineering at the University of Illinois ...

A characteristic feature of all stem cells is their ability to self-renew. But how is this potential maintained throughout life? Scientists at the German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ) and the Heidelberg Institute for Stem Cell Technology and Experimental Medicine* (HI-STEM) have now discovered in mice that cells in the so-called "stem cell niche" are responsible for this: Blood vessel cells of the niche produce a factor that stimulates blood stem cells and thus maintains their self-renewal capacity. During aging, production of this factor ceases and blood stem cells begin to age.

Throughout life, blood stem cells in the bone marrow ensure that our body is adequately supplied with mature blood cells. If there is no current need for cell ...

Much of the earth's carbon is trapped in soil, and scientists have assumed that potential climate-warming compounds would safely stay there for centuries. But new research from Princeton University shows that carbon molecules can potentially escape the soil much faster than previously thought. The findings suggest a key role for some types of soil bacteria, which can produce enzymes that break down large carbon-based molecules and allow carbon dioxide to escape into the air.

More carbon is stored in soil than in all the planet's plants and atmosphere combined, and soil absorbs about 20% of human-generated carbon emissions. Yet, factors that affect carbon storage and release from soil have been challenging to study, placing limits on the relevance of ...

DALLAS, Jan. 27, 2021 -- Heart disease remains the leading cause of death worldwide, according to the American Heart Association's Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics -- 2021 Update, published today in the Association's flagship journal Circulation, and experts warn that the broad influence of the COVID-19 pandemic will likely continue to extend that ranking for years to come.

Globally, nearly 18.6 million people died of cardiovascular disease in 2019, the latest year for which worldwide statistics are calculated. That reflects a 17.1% increase over the past decade. There were more than 523.2 million cases of cardiovascular disease in 2019, an increase ...

(Boston)--When severely or chronically injured, the liver loses its ability to regenerate.

A new study led by researchers at the Center for Regenerative Medicine at Boston University School of Medicine (BUSM) and Boston Medical Center (BMC) now describes a safe new potential therapeutic tool for the recovery of liver function in chronic and acute liver diseases.

Researchers utilized the lipid nanoparticle-encapsulated messenger RNA (mRNA-LNP) currently used in COVID-19 vaccines, to deliver regenerative factors to injured livers in a timely, controlled fashion. "We found that this intervention successfully induces the rapid expansion of the functional ...

New York - The results of the Peoples' Climate Vote, the world's biggest ever survey of public opinion on climate change are published today. Covering 50 countries with over half of the world's population, the survey includes over half a million people under the age of 18, a key constituency on climate change that is typically unable to vote yet in regular elections.

Detailed results broken down by age, gender, and education level will be shared with governments around the world by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), ...

DALLAS (SMU) - Wildfires are the enemy when they threaten homes in California and elsewhere. But a new study led by SMU suggests that people living in fire-prone places can learn to manage fire as an ally to prevent dangerous blazes, just like people who lived nearly 1,000 years ago.

"We shouldn't be asking how to avoid fire and smoke," said SMU anthropologist and lead author Christopher Roos. "We should ask ourselves what kind of fire and smoke do we want to coexist with."

An interdisciplinary team of scientists published a study in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences documenting centuries of fire management ...

The United States Department of Agriculture identifies a group of "big eight" foods that causes 90% of food allergies. Among these foods are wheat and peanuts.

Sachin Rustgi, a member of the Crop Science Society of America, studies how we can use breeding to develop less allergenic varieties of these foods. Rustgi recently presented his research at the virtual 2020 ASA-CSSA-SSSA Annual Meeting.

Allergic reactions caused by wheat and peanuts can be prevented by avoiding these foods, of course. "While that sounds simple, it is difficult in practice," says Rustgi.

Avoiding wheat and peanuts means losing out ...

Tsukuba, Japan - Tomatoes are one of the most popular types of fresh produce consumed worldwide, as well as being an important ingredient in many manufactured foods.

As with other cultivated crops, some potentially useful genes that were present in its South American ancestors were lost during domestication and breeding of the modern tomato, Solanum lycopersicum var. lycopersicum.

Because of its importance as a crop, the tomato genome sequence was completed and published as long ago as 2012, with later additions and improvements. Now, the team at University of Tsukuba, in collaboration with TOKITA Seed Co. Ltd, have produced high-quality genome sequences of two wild ancestors of tomato from Peru, Solanum pimpinellifolium ...

Children of all ages can completely bypass age verification measures to sign-up to the world's most popular social media apps including Snapchat, Instagram, TikTok, Facebook, WhatsApp, Messenger, Skype and Discord by simply lying about their age, researchers at Lero, the Science Foundation Ireland Research Centre for Software have discovered.

And even potential age verification solutions identified by the research team can be easily sidestepped by children, according to the team's most recent study: Digital Age of Consent and Age Verification: Can They Protect Children?

Lead researcher Lero's Dr Liliana Pasquale, assistant professor at University College ...