A NEAT reduction of complex neuronal models accelerates brain research

2021-01-27

(Press-News.org) Neurons, the fundamental units of the brain, are complex computers by themselves. They receive input signals on a tree-like structure - the dendrite. This structure does more than simply collect the input signals: it integrates and compares them to find those special combinations that are important for the neurons' role in the brain. Moreover, the dendrites of neurons come in a variety of shapes and forms, indicating that distinct neurons may have separate roles in the brain.

A simple yet faithful model

In neuroscience, there has historically been a tradeoff between a model's faithfulness to the underlying biological neuron and its complexity. Neuroscientists have constructed detailed computational models of many different types of dendrites. These models mimic the behavior of real dendrites to a high degree of accuracy. The tradeoff, however, is that such models are very complex. Thus, it is hard to exhaustively characterize all possible responses of such models and to simulate them on a computer. Even the most powerful computers can only simulate a small fraction of the neurons in any given brain area.

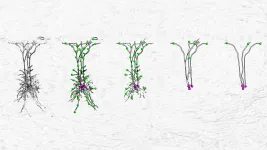

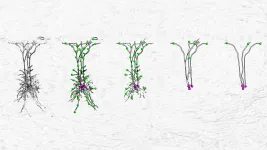

Researchers from the Department of Physiology at the University of Bern have long sought to understand the role of dendrites in computations carried out by the brain. On the one hand, they have constructed detailed models of dendrites from experimental measurements, and on the other hand they have constructed neural network models with highly abstract dendrites to learn computations such as object recognition. A new study set out to find a computational method to make highly detailed models of neurons simpler, while retaining a high degree of faithfulness. This work emerged from the collaboration between experimental and computational neuroscientists from the research groups of Prof. Thomas Nevian and Prof. Walter Senn, and was led by Dr Willem Wybo. "We wanted the method to be flexible, so that it could be applied to all types of dendrites. We also wanted it to be accurate, so that it could faithfully capture the most important functions of any given dendrite. With these simpler models, neural responses can more easily be characterized and simulation of large networks of neurons with dendrites can be conducted," Dr Wybo explains.

This new approach exploits an elegant mathematical relation between the responses of detailed dendrite models and of simplified dendrite models. Due to this mathematical relation, the objective that is optimized is linear in the parameters of the simplified model. "This crucial observation allowed us to use the well-known linear least squares method to find the optimized parameters. This method is very efficient compared to methods that use non-linear parameter searches, but also achieves a high degree of accuracy," says Prof. Senn.

Tools available for AI applications

The main result of the work is the methodology itself: a flexible yet accurate way to construct reduced neuron models from experimental data and morphological reconstructions. "Our methodology shatters the perceived tradeoff between faithfulness and complexity, by showing that extremely simplified models can still capture much of the important response properties of real biological neurons," Prof. Senn explains. "Which also provides insight into 'the essential dendrite', the simplest possible dendrite model that still captures all possible responses of the real dendrite from which it is derived," Dr Wybo adds.

Thus, in specific situations, hard bounds can be established on how much a dendrite can be simplified, while retaining its important response properties. "Furthermore, our methodology greatly simplifies deriving neuron models directly from experimental data," Prof. Senn highlights, who is also a member of the steering committe of the Center for Artifical Intelligence (CAIM) of the University of Bern. The methodology has been compiled into NEAT (NEural Analysis Toolkit) - an open-source software toolbox that automatizes the simplification process. NEAT is publicly available on GitHub.

The neurons used currently in AI applications are exceedingly simplistic compared to their biological counterparts, as they don't include dendrites at all. Neuroscientists believe that including dendrite-like operations in artificial neural networks will lead to the next leap in AI technology. By enabling the inclusion of very simple, but very accurate dendrite models in neural networks, this new approach and toolkit provide an important step towards that goal.

This work was supported by the Human Brain Project, by the Swiss National Science foundation and by the European Research Council.

INFORMATION:

[Attachments] See images for this press release:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-01-27

Being constantly flooded by a mass of stimuli, it is impossible for us to react to all of them. The same holds true for a little fish. Which stimuli should it pay attention to and which not? Scientists at the Max Planck Institute of Neurobiology have now deciphered the neuronal circuit that zebrafish use to prioritize visual stimuli. Surrounded by predators, a fish can thus choose its escape route from this predicament.

Even though we are not exposed to predators, we still have to decide which stimuli we pay attention to - for example, when crossing a street. Which cars should we avoid, which ones can we ignore?

"The ...

2021-01-27

A massive simulation of the cosmos and a nod to the next generation of computing

A team of physicists and computer scientists from the U.S. Department of Energy's (DOE) Argonne National Laboratory performed one of the five largest cosmological simulations ever. Data from the simulation will inform sky maps to aid leading large-scale cosmological experiments.

The simulation, called the Last Journey, follows the distribution of mass across the universe over time -- in other words, how gravity causes a mysterious invisible substance called "dark matter" to clump ...

2021-01-27

Many genetic mutations have been found to be associated with a person's risk of developing Parkinson's disease. Yet for most of these variants, the mechanism through which they act remains unclear.

Now a new study in Nature led by a team from the University of Pennsylvania has revealed how two different variations--one that increases disease risk and leads to more severe disease in people who develop Parkinson's and another that reduces risk--manifest in the body.

The work, led by Dejian Ren, a professor in the School of Arts & Sciences' Department of Biology, showed that the variation that raises disease risk, which about 17% of people possess, causes a reduction in function of an ion channel ...

2021-01-27

Dr. Richi Gill, MD, is back at work, able to enjoy time with his family in the evening and get a good night's sleep, thanks to research. Three years ago, Gill broke his neck in a boogie board accident while on vacation with his young family. Getting mobile again with the use of a wheelchair is the first thing, Gill says, most people notice. However, for those with a spinal cord injury (SCI), what is happening inside the body also severely affects their quality of life.

"What many people don't realize is that a spinal cord injury prevents some systems within the body from regulating automatically," ...

2021-01-27

Among infectious diseases that have caused pandemics and epidemics, smallpox stands out as a success story. Smallpox vaccination led to the disease's eradication in the twentieth century. Until very recently, smallpox vaccine was delivered using a technique known as skin scarification (s.s.), in which the skin is repeatedly scratched with a needle before a solution of the vaccine is applied. Almost all other vaccines today are delivered via intramuscular injection, with a needle going directly into the muscle, or through subcutaneous injection to the layer of tissue beneath the skin. But Thomas Kupper, MD, chair of the Department of Dermatology, and colleagues, had reason to suspect that vaccines delivered ...

2021-01-27

URBANA, Ill. - With cities around the globe locking down yet again amid soaring COVID-19 numbers, could seasonality be partially to blame? New research from the University of Illinois says yes.

In a paper published in Evolutionary Bioinformatics, Illinois researchers show COVID-19 cases and mortality rates, among other epidemiological metrics, are significantly correlated with temperature and latitude across 221 countries.

"One conclusion is that the disease may be seasonal, like the flu. This is very relevant to what we should expect from now on after the vaccine controls these first waves of COVID-19," says Gustavo ...

2021-01-27

An upsurge of matter from deep beneath the Earth's crust could be pushing the continents of North and South America further apart from Europe and Africa, new research has found.

The plates attached to the Americas are moving apart from those attached to Europe and Africa by four centimetres per year. In between these continents lies the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, a site where new plates are formed and a dividing line between plates moving to the west and those moving to the east; beneath this ridge, material rises to replace the space left by the plates as they move apart.

Conventional wisdom is that this process is normally driven by distant gravity forces as denser parts of the plates sink back into the Earth. However, the driving force behind the separation of the Atlantic ...

2021-01-27

Scientists have resolved a key climate change mystery, showing that the annual global temperature today is the warmest of the past 10,000 years - contrary to recent research, according to a Rutgers-led study in the journal Nature.

The long-standing mystery is called the "Holocene temperature conundrum," with some skeptics contending that climate model predictions of future warming must be wrong. The scientists say their findings will challenge long-held views on the temperature history in the Holocene era, which began about 12,000 years ago.

"Our reconstruction shows that the first half of the Holocene was colder than in industrial times due to the cooling effects of remnant ice sheets from the previous glacial period - contrary to previous reconstructions of global temperatures," ...

2021-01-27

STOCKHOLM: With impacts from climate change threatening to be as abrupt and far-reaching in the coming years as the current pandemic, leading scientists have released a compilation of the 10 most important insights on the climate from the last year to help inform collective action on the ongoing climate crisis.

In a report presented today to Patricia Espinosa, Executive Secretary of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), report authors outlined some of 2020's most important findings within the field of climate science, ranging from improved models that reveal the need for aggressive emission cuts in order to meet the Paris Agreement to the growing use of human rights litigation to catalyze climate action.

The report alleviates some worries that ...

2021-01-27

In experiments at the Paul Scherrer Institute PSI, an international research collaboration has measured the radius of the atomic nucleus of helium five times more precisely than ever before. With the aid of the new value, fundamental physical theories can be tested and natural constants can be determined even more precisely. For their measurements, the researchers needed muons - these particles are similar to electrons but are around 200 times heavier. PSI is the only research site in the world where enough so-called low-energy muons are produced for such experiments. The researchers are publishing their results today in the journal Nature.

After hydrogen, helium is the second most abundant element in the universe. Around one-fourth of the ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] A NEAT reduction of complex neuronal models accelerates brain research