(Press-News.org) People who take opioid medications for chronic pain may have a hard time finding a new primary care clinic that will take them on as a patient if they need one, according to a new "secret shopper" study of hundreds of clinics in states across the country.

Stigma against long-term users of prescription opioids, likely related to the prospect of taking on a patient who might have an opioid use disorder or addiction, appears to play a role, the University of Michigan research suggests.

Simulated patients who said their doctor or other primary care provider had retired were more likely to be told they could be accepted as new patients, compared with those who said their provider had stopped prescribing opioids to them for an unknown reason.

The U-M primary care provider and health care researcher who led the new study, Pooja Lagisetty, M.D., M.Sc., hopes that her team's new findings published in the journal Pain could help primary care clinics look at their practices regarding existing or prospective new patients.

"We need to make sure we're training prescribers and their teams in addressing the systemic biases that this research highlights," says Lagisetty, a general internal medicine physician at Michigan Medicine, U-M's academic medical center. "We shouldn't even be thinking about the reason that patients are giving when they seek to access care.

"Even if you think that someone is using opioids for a reason other than pain, or that long-term opioids are not an effective pain care strategy, those are exactly the patients we in primary are should be seeing," she adds. "Restricting their primary care access limits their ability to engage in pain-focused care and potentially addiction-focused care."

It also worsens stigma, she says, by suggesting that people using opioids for pain are more worthy of receiving care than those who may have addiction.

She and her colleagues had seen signs of stigma against patients on long-term opioids for non-cancer pain in a previous study that used the "secret shopper" technique to call clinics in Michigan. But the new study takes that to a new level, with data from 452 clinics in nine states.

Each clinic responded to two calls, separated by time, from a female caller who asked if the clinic was taking new patients, said she was covered by a major insurer in the area, and said she had been taking opioids for years for pain. Depending on the call, she then either said that her last provider had retired or stopped prescribing opioids, leading her to seek a new primary care clinic and asking if their providers would potentially continue to prescribe opioids after a visit.

All of the clinics included in the study said they were taking new patients, but when the patient mentioned wanting to receive opioids, 43% of the clinics said they were no longer willing to schedule the appointment.

"This suggests that many clinics are likely just shutting their door to any patient needing an opioid prescription despite the reason for needing a new provider," says Lagisetty, who is also a member of the U-M Institute for Healthcare Policy and Innovation. "Clinics often stated to the patient that this was due to new policies, fear of legal ramifications, or administrative burdens."

She adds that barriers to treating opioid addiction in a primary care setting, including the special training needed to prescribe buprenorphine and the added support needed to help patients receiving medications for opioid use disorder, may have contributed to this. Recent signs that the federal requirements may be relaxed could help change this, but only if primary care providers receive help and training in providing this kind of care.

Nearly one-third (32%) of the clinics said they would schedule the patient for an appointment and the primary care provider would potentially continue to prescribe opioids, no matter which scenario the patient gave.

But the remaining 25% of clinics gave mixed signals when called twice. In those clinics, patients had nearly 2 times the likelihood of getting scheduled if their prior physician had retired as compared to those who said their last doctor had stopped prescribing for unknown reasons.

"In these cases, where clinics gave different answers depending on the scenario presented, it is harder to argue that stigma around opioid use, pain, and addiction is not playing a role in clinic decision-making," says Lagisetty.

INFORMATION:

In addition to Lagisetty, the study's authors are Colin Macleod, Jennifer Thomas, Stephanie Slat, Adrianne Kehne, Michele Heisler, and Amy S.B. Bohnert of the University of Michigan, and senior author Kipling Bohnert of Michigan State University.

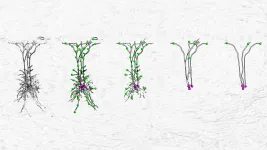

Neurons, the fundamental units of the brain, are complex computers by themselves. They receive input signals on a tree-like structure - the dendrite. This structure does more than simply collect the input signals: it integrates and compares them to find those special combinations that are important for the neurons' role in the brain. Moreover, the dendrites of neurons come in a variety of shapes and forms, indicating that distinct neurons may have separate roles in the brain.

A simple yet faithful model

In neuroscience, there has historically been a tradeoff between a model's faithfulness to the underlying biological neuron and its complexity. Neuroscientists have constructed ...

Being constantly flooded by a mass of stimuli, it is impossible for us to react to all of them. The same holds true for a little fish. Which stimuli should it pay attention to and which not? Scientists at the Max Planck Institute of Neurobiology have now deciphered the neuronal circuit that zebrafish use to prioritize visual stimuli. Surrounded by predators, a fish can thus choose its escape route from this predicament.

Even though we are not exposed to predators, we still have to decide which stimuli we pay attention to - for example, when crossing a street. Which cars should we avoid, which ones can we ignore?

"The ...

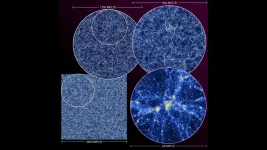

A massive simulation of the cosmos and a nod to the next generation of computing

A team of physicists and computer scientists from the U.S. Department of Energy's (DOE) Argonne National Laboratory performed one of the five largest cosmological simulations ever. Data from the simulation will inform sky maps to aid leading large-scale cosmological experiments.

The simulation, called the Last Journey, follows the distribution of mass across the universe over time -- in other words, how gravity causes a mysterious invisible substance called "dark matter" to clump ...

Many genetic mutations have been found to be associated with a person's risk of developing Parkinson's disease. Yet for most of these variants, the mechanism through which they act remains unclear.

Now a new study in Nature led by a team from the University of Pennsylvania has revealed how two different variations--one that increases disease risk and leads to more severe disease in people who develop Parkinson's and another that reduces risk--manifest in the body.

The work, led by Dejian Ren, a professor in the School of Arts & Sciences' Department of Biology, showed that the variation that raises disease risk, which about 17% of people possess, causes a reduction in function of an ion channel ...

Dr. Richi Gill, MD, is back at work, able to enjoy time with his family in the evening and get a good night's sleep, thanks to research. Three years ago, Gill broke his neck in a boogie board accident while on vacation with his young family. Getting mobile again with the use of a wheelchair is the first thing, Gill says, most people notice. However, for those with a spinal cord injury (SCI), what is happening inside the body also severely affects their quality of life.

"What many people don't realize is that a spinal cord injury prevents some systems within the body from regulating automatically," ...

Among infectious diseases that have caused pandemics and epidemics, smallpox stands out as a success story. Smallpox vaccination led to the disease's eradication in the twentieth century. Until very recently, smallpox vaccine was delivered using a technique known as skin scarification (s.s.), in which the skin is repeatedly scratched with a needle before a solution of the vaccine is applied. Almost all other vaccines today are delivered via intramuscular injection, with a needle going directly into the muscle, or through subcutaneous injection to the layer of tissue beneath the skin. But Thomas Kupper, MD, chair of the Department of Dermatology, and colleagues, had reason to suspect that vaccines delivered ...

URBANA, Ill. - With cities around the globe locking down yet again amid soaring COVID-19 numbers, could seasonality be partially to blame? New research from the University of Illinois says yes.

In a paper published in Evolutionary Bioinformatics, Illinois researchers show COVID-19 cases and mortality rates, among other epidemiological metrics, are significantly correlated with temperature and latitude across 221 countries.

"One conclusion is that the disease may be seasonal, like the flu. This is very relevant to what we should expect from now on after the vaccine controls these first waves of COVID-19," says Gustavo ...

An upsurge of matter from deep beneath the Earth's crust could be pushing the continents of North and South America further apart from Europe and Africa, new research has found.

The plates attached to the Americas are moving apart from those attached to Europe and Africa by four centimetres per year. In between these continents lies the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, a site where new plates are formed and a dividing line between plates moving to the west and those moving to the east; beneath this ridge, material rises to replace the space left by the plates as they move apart.

Conventional wisdom is that this process is normally driven by distant gravity forces as denser parts of the plates sink back into the Earth. However, the driving force behind the separation of the Atlantic ...

Scientists have resolved a key climate change mystery, showing that the annual global temperature today is the warmest of the past 10,000 years - contrary to recent research, according to a Rutgers-led study in the journal Nature.

The long-standing mystery is called the "Holocene temperature conundrum," with some skeptics contending that climate model predictions of future warming must be wrong. The scientists say their findings will challenge long-held views on the temperature history in the Holocene era, which began about 12,000 years ago.

"Our reconstruction shows that the first half of the Holocene was colder than in industrial times due to the cooling effects of remnant ice sheets from the previous glacial period - contrary to previous reconstructions of global temperatures," ...

STOCKHOLM: With impacts from climate change threatening to be as abrupt and far-reaching in the coming years as the current pandemic, leading scientists have released a compilation of the 10 most important insights on the climate from the last year to help inform collective action on the ongoing climate crisis.

In a report presented today to Patricia Espinosa, Executive Secretary of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), report authors outlined some of 2020's most important findings within the field of climate science, ranging from improved models that reveal the need for aggressive emission cuts in order to meet the Paris Agreement to the growing use of human rights litigation to catalyze climate action.

The report alleviates some worries that ...