(Press-News.org) Science is society's best method for understanding the world, yet many people in the field are unhappy with the way it works. Rules and procedures meant to promote innovative research can have perverse side-effects that harm both science and scientists. One of these - the 'priority rule' - rewards scientists who make discoveries with prestige, prizes and better career opportunities, depriving the runners-up of similar perks. Researchers at University of Technology Eindhoven (TU/e) and the Arizona State University in the US have developed a new model to better understand this rule, and see if current reforms to improve the system actually make sense. Their study was published in Nature Human Behaviour.

"Over the past decade, there have been growing concerns that something is "rotten" in the state of science", says Leonid Tiokhin, researcher at the Human Technology Interaction group at TU/e and lead author of the paper. "Scientists are realizing that many rules and procedures are dictated by norms and historical precedent, rather than principled reasons that serve efficiency and reliability. Worse, there is growing evidence that some norms have adverse side-effects that can hurt both science and scientists."

A well-known example is the general preference for positive over negative results. If journals only publish positive results, this creates 'publication bias', where the only results that get published are those that convincingly show correlation or causation, leaving out negative results that are just as relevant.

Another practice that may do more harm than good is valuing priority of discovery, which rewards scientist who are first to publish their findings with disproportionate prestige, prizes and career opportunities.

The winner takes it all

"Many scientists have sleepless nights worrying about being 'scooped' - fearing that their work won't be considered "novel" enough for the highest-impact scientific journals," says Tiokhin. The priority rule has been around for centuries. In the 17th century, Newton and Leibniz haggled over who invented calculus. And in the 19th century, Charles Darwin rushed the publication of his work on evolution by means of natural selection to avoid being scooped by Alfred Russel Wallace.

"Rewarding priority is understandable and has some benefits. However, it comes at a cost," says Tiokhiin, "Rewards for priority may tempt scientists to sacrifice the quality of their research and cut corners."

"This is partly why some academic publishers, such as PLOS and eLife, decided to offer 'scoop protection', allowing researchers to publish findings identical to those already published within a certain timeframe. The problem is that we don't yet have a good idea about whether these reforms make sense."

Modelling the priority rule

To figure out the effects of rewarding priority (and whether recent reforms offer any solution for its potential drawbacks) Tiokhin and his colleagues developed an 'evolutionary agent-based model'. This computer model simulates how a group of scientists investigate or abandon research questions, depending on factors such as the type of results (positive or negative) and the novelty of the research (the cost of being 'scooped').

The scientists were simulated as "agents" who are more likely to progress in their careers if they conduct research in a way that nets them sufficient rewards (such as money or prestige). By varying the way that science was structured and which types of findings were most rewarded, the researchers were able to examine how agents changed their behavior over time and what the consequences of these changes were for science as a whole.

No panacea

The researchers found that a culture that rewards priority - where there is a big cost to being scooped - can have harmful effects. Among other things, it motivates scientists to conduct 'quick and dirty' studies, so that they can be first to publish. This reduces the quality of their work and harms the reliability of science as a whole.

The model also suggests that some form of scoop protection, as introduced by PLOS and eLife, works. "It reduces the temptation to rush the research and gives researchers more time to collect additional data," says Tiokhin. "However, we should keep in mind that scoop protection is no panacea."

This is because scoop protection motivates some scientists to continue with a research line even after several results have been published, which reduces the total number of interesting questions investigated. The model also shows that even with scoop protection, scientists can be tempted to run many small studies if the costs of starting a new project (start-up costs) are low and the rewards for negative results are high.

The 'benefit' of inefficiency

"So while scoop-protection reforms are helpful, they are not sufficient to incentivize high-quality research or a reliable published literature," according to Tiokhin. "Our results suggest that we should also consider having some form of start-up costs, such as asking scientists to pre-register their studies or get their research plans criticized before they begin collecting data."

"We also learned that inefficiency in science is not always a bad thing. On the contrary: inefficiencies force researchers to think twice before starting a new study."

Other possible solutions to offset the negative effects of the priority rule are reducing data-collection inefficiencies (to make it easier to gather lots of data) and rewarding study quality (to avoid statistically 'underpowered' studies).

Metaresearch

Tiokhin has a personal motive for his work, which is known as 'meta-research', the use of the scientific method to study research itself. "When I was doing my PhD research in the US, I was frustrated by the way that science works. Like many researchers, I was idealistic when I got into science. But I soon found out that research is often not about figuring out the nature of reality, but about playing by the rules of the game. That often means getting your work published in the "right" journals, preferably with results that are novel and statistically significant."

"The problem is that I don't like playing by arbitrary rules. With my research, I want to understand what rules for recognizing and rewarding scientists actually make sense and generate better outcomes for science as a whole."

INFORMATION:

More info

Leonid Tiokhin, Minhua Yan, Thomas J.H. Morgan, Competition for priority harms the reliability of science but reforms can help, Nature Human Behaviour (DOI: 10.1038/s41562-020-01040-1)

What The Study Did: This study finds that being a health care worker isn't associated with poorer outcomes among patients hospitalized with COVID-19.

Authors: Nauzer Forbes, M.D., M.Sc., of the University of Calgary in Canada, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.35699)

Editor's Note: The article includes conflict of interest disclosures. Please see the article for additional information, ...

Risky behaviors such as smoking, alcohol and drug use, speeding, or frequently changing sexual partners result in enormous health and economic consequences and lead to associated costs of an estimated 600 billion dollars a year in the US alone. In order to define measures that could reduce these costs, a better understanding of the basis and mechanisms of risk-taking is needed.

Functional and anatomical differences

UZH neuro-economists Goekhan Aydogan, Todd Hare and Christian Ruff, together with an international research team looked at the genetic characteristics that correlate with risk-taking behavior. Using a representative sample of 25,000 people, the researchers examined the relationship ...

BOSTON - A nationwide panel of experts has developed the first mammography guidelines for older survivors of breast cancer, providing a framework for discussions between survivors and their physicians on the pros and cons of screening in survivors' later years.

The guidelines, published online today in a paper in JAMA Oncology, recommend discontinuing routine mammograms for survivors with a life expectancy under five years; considering stopping screening for those with a 5-10-year life expectancy; and continuing mammography for those whose life expectancy is greater than 10 years. The guidelines will be complemented by printed materials to help survivors gauge their risk of cancer recurring in the breast and weigh the potential benefits and drawbacks of mammography with ...

Science is society's best method for understanding the world. Yet many scientists are unhappy with the way it works, and there are growing concerns that there is something "broken" in current scientific practice. Many of the rules and procedures that are meant to promote innovative research are little more than historical precedents with little reason to suppose they encourage efficient or reliable discoveries. Worse, they can have perverse side-effects that harm both science and scientists. A well-known example is the general preference for positive over negative results, which creates a "publication bias" that gives the false ...

CLEVELAND - Cleveland Clinic researchers have described for the first time how Zika virus (ZIKV) causes one of the most common birth defects associated with prenatal infection, called brain calcification, according to new study findings published in Nature Microbiology.

The findings may reveal novel strategies to prevent prenatal ZIKV brain calcification and offer important insights into how calcifications form in other congenital infections.

"Brain calcification has been linked to several developmental defects in infants, including motor disorders, cognitive disability, eye abnormalities, hearing deficits and seizures, so it's important to better understand the mechanisms of how they develop," said Jae Jung, ...

Advances in DNA sequencing have uncovered a rare syndrome which is caused by variations in the gene SATB1.

The study, co-authored by academics from Oxford Brookes University (UK), University of Lausanne (Switzerland), Radboud University (The Netherlands), University of Oxford (UK), University of Manchester (UK) and led by Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics (The Netherlands), discovered three classes of mutations within the gene SATB1, resulting in three variations of a neurodevelopmental disorder with varying symptoms ranging from epilepsy to muscle tone abnormalities.

Recognition of disorder will increase understanding and diagnosis

An international team of geneticists and clinicians from 12 countries identified 42 patients with mutations in the gene ...

People with sleep disorders commonly have a misperception about their actual sleep behaviour. A research group led by Karin Trimmel and Stefan Seidel from MedUni Vienna's Department of Neurology (Outpatient Clinic for Sleep Disorders and Sleep-Related Disorders) analysed polysomnography results to identify the types of sleep disorder that are associated with a discrepancy between self-reported and objective sleep parameters and whether there are any factors that influence this. The main finding: irrespective of age, gender or screening setting, insomnia patients are most likely to underestimate how long they sleep. The study has been published in the highly regarded Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine.

Patients' misperceptions about the actual time that they sleep is a well-known ...

The ability to manipulate near-infrared (NIR) radiation has the potential to enable a plethora of technologies not only for the biomedical sector (where the semitransparency of human tissue is a clear advantage) but also for security (e.g. biometrics) and ICT (information and communication technology), with the most obvious application being to (nearly or in)visible light communications (VLCs) and related ramifications, including the imminent Internet of Things (IoT) revolution. Compared with inorganic semiconductors, organic NIR sources offer cheap fabrication over large areas, mechanical flexibility, conformability, ...

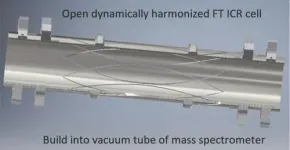

Mass spectrometers are widely used to analyze highly complex chemical and biological mixtures. Skoltech scientists have developed a new version of a mass spectrometer that uses rotation frequencies of ionized molecules in strong magnetic fields to measure masses with higher accuracy (FT ICR). The team has designed an ion trap that ensures the utmost resolving power in ultra-strong magnetic fields. The research was published in the journal Analytical Chemistry.

The ion trap is shaped like a cylinder made up of electrodes, with electric and magnetic fields generated inside. The exact masses of the test sample's ions can be determined from their rotation frequencies. The electrodes must create a harmonized field of a particular shape ...

Skoltech researchers and their colleagues from Russia and Germany have designed an on-chip printed 'electronic nose' that serves as a proof of concept for low-cost and sensitive devices to be used in portable electronics and healthcare. The paper was published in the journal ACS Applied Materials Interfaces.

The rapidly growing fields of the Internet of Things (IoT) and advanced medical diagnostics require small, cost-effective, low-powered yet reasonably sensitive, and selective gas-analytical systems like so-called 'electronic noses.' These ...