(Press-News.org) Parasitic worms could hold the key to living longer and free of chronic disease, according to a review article published today in the open-access eLife journal.

The review looks at the growing evidence to suggest that losing our 'old friend' helminth parasites, which used to live relatively harmlessly in our bodies, can cause ageing-associated inflammation. It raises the possibility that carefully controlled, restorative helminth treatments could prevent ageing and protect against diseases such as heart disease and dementia.

"A decline in exposure to commensal microbes and gut helminths in developed countries has been linked to increased prevalence of allergic and autoimmune inflammatory disorders - the so-called 'old friends hypothesis'," explains author Bruce Zhang, Undergraduate Assistant at the UCL Institute of Healthy Ageing, London, UK. "A further possibility is that this loss of 'old friend' microbes and helminths increases the sterile, ageing-associated inflammation known as inflammageing."

Inflammageing is increasingly thought to be a contributory factor to the major diseases of later life, including heart disease, dementia, cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, osteoporosis, age-related eye disease and - more recently - symptom severity during SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) infections.

One theory is that changes in the gut microbiome might cause inflammageing, but until now little consideration has been given to the role of organisms comprising the macrobiome - the ecosystem of macro-organisms - including helminth parasites such as flukes, tapeworms and nematodes.

Helminths have infected humans throughout our evolutionary history, and as a result have become master manipulators of our immune response. Humans, in turn, have evolved levels of tolerance to their presence.

In their article, Zhang and co-author David Gems, Professor of Biogerontology and Research Director at the UCL Institute of Healthy Ageing, review the evidence for helminth therapy in two areas: treating known inflammatory disorders, such as coeliac disease, and stopping or reversing inflammageing as part of the ageing process.

They reveal how the loss of helminths has so far been linked to a range of inflammatory diseases, including asthma, atopic eczema, inflammatory bowel disease, multiple sclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis and diabetes. Some studies have shown that natural infection with helminths can alleviate disease symptoms, for example in multiple sclerosis and eczema, while other studies in animal models suggest that intentional infection with helminths could have benefits against disease.

The safer, and perhaps more palatable, option is the concept of using helminth-derived proteins to achieve the same therapeutic benefits. This was tested recently in mice and shown to prevent the age-related decline in gut barrier integrity usually seen with a high-calorie diet. It also had beneficial effects on fat tissue, which is known to be a major source of inflammageing.

The authors speculate that if helminths have anti-inflammageing properties, you would expect to see lower rates of inflammageing-related disease in areas where helminth infection is more common. There is some evidence to support this. For example, in a region in Eastern India endemic for lymphatic filariasis caused by filarial worms, not a single person with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) tested positive for circulating filarial antigens, whereas a much higher proportion (40%) of people without RA tested positive for the nematode. Other epidemiological studies have shown protection from helminths against type 2 diabetes and blocked arteries.

"It goes without saying that improvements in hygiene and elimination of helminth parasites have been of incalculable benefit to humanity, but a cost coupled to this benefit is abnormalities of immune function," Gems concludes. "In the wake of successes during the last century in eliminating the evil of helminths, the time now seems right to further explore their possible benefits, particularly for our ageing population - strange as this may sound."

INFORMATION:

Reference

The paper 'Gross ways to live long: parasitic worms as an anti-inflammaging therapy?' can be freely accessed online at https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.65180. Contents, including text, figures and data, are free to reuse under a CC BY 4.0 license.

This study will be published as part of eLife's special issue on evolutionary medicine. For more information, visit https://elifesciences.org/inside-elife/bb34a238/special-issue-call-for-papers-in-evolutionary-medicine.

Media contact

Emily Packer, Media Relations Manager

eLife

e.packer@elifesciences.org

01223 855373

About eLife

eLife is a non-profit organisation created by funders and led by researchers. Our mission is to accelerate discovery by operating a platform for research communication that encourages and recognises the most responsible behaviours. We aim to publish work of the highest standards and importance in all areas of biology and medicine, including Immunology and Inflammation, while exploring creative new ways to improve how research is assessed and published. eLife receives financial support and strategic guidance from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation, the Max Planck Society and Wellcome. Learn more at https://elifesciences.org/about.

To read the latest Immunology and Inflammation research published in eLife, visit https://elifesciences.org/subjects/immunology-inflammation.

A greater exposure to air pollution at the very start of life was associated with a detrimental effect on people's cognitive skills up to 60 years later, the research found.

Researchers at the University of Edinburgh tested the general intelligence of more than 500 people aged approximately 70 years using a test they had all completed at the age of 11 years.

The participants then repeated the same test at the ages of 76 and 79 years.

A record of where each person had lived throughout their life was used to estimate the level of air pollution they had experienced in their early years.

The team used statistical models to analyse the relationship between a person's exposure to air pollution ...

To evaluate the chemical composition of food from a physiological point of view, it is important to know the functions of the receptors that interact with food ingredients. These include receptors for bitter compounds, which first evolved during evolution in bony fishes such as the coelacanth. What 400 million years of evolutionary history reveal about the function of both fish and human bitter receptors was recently published in the journal Genome Biology and Evolution by a team of researchers led by the Leibniz Institute for Food Systems Biology at the Technical University of Munich and the University of Cologne.

Evolutionarily, bitter receptors are a relatively recent invention of nature compared ...

A process that releases iron in response to stress may contribute to heart failure, and blocking this process could be a way of protecting the heart, suggests a study in mice published today in eLife.

People with heart failure often have an iron deficiency, leading some scientists to suspect that problems with iron processing in the body may play a role in this condition. The study explains one way that iron processing may contribute to heart failure and suggests potential treatment approaches to protect the heart.

"Iron is essential for many processes in the body including oxygen transport, but too much iron can lead to a build-up of unstable oxygen molecules that can kill cells," says ...

Trees are by far the tallest organisms on Earth. Height growth is made possible by a specialized vascular system that conducts water from the roots to the leaves with high efficiency, while simultaneously providing stability. The so-called xylem, also known as wood, is a network of hollow cells with extremely strong cell walls that reinforce the cells against the mechanical conflicts arising from growing tall. These walls wrap around the cells in filigree band and spiral patterns. So far, it is only partly known, how these patterns are created. Scientists from the Max Planck Institute for Molecular Plant Physiology in Golm/Potsdam and from ...

Carbon dioxide (CO2) is one of the major greenhouse gases causing global warming. If carbon dioxide could be converted into energy, it would be killing two birds with one stone in addressing the environmental issues. A joint research team led by City University of Hong Kong (CityU) has developed a new photocatalyst which can produce methane fuel (CH4) selectively and effectively from carbon dioxide using sunlight. According to their research, the quantity of methane produced was almost doubled in the first 8 hours of the reaction process.

The research was led by Dr Ng Yun-hau, Associate Professor in the ...

King Richard III's involvement in one of the most notorious and emotive mysteries in English history may be a step closer to being confirmed following a new study by Professor Tim Thornton of the University of Huddersfield.

Richard has long been held responsible of the murder of his nephews King Edward V and his brother, Richard, duke of York - dubbed 'the Princes in the Tower' - in a dispute about succession to the throne. The pair were held in the Tower of London, but disappeared from public view in 1483 with Richard taking the blame following his death two years later.

It has become of the most ...

In the United States only about 1.3 percent of all vehicles sold last year were battery powered. And about 90 percent of those sales were by one company -- Tesla. What has Tesla done right and where have other electric vehicle makers gone wrong?

Electric vehicles cannot succeed without developing a nationwide network of fast-charging networks in parallel with the cars. Current EV business models are doomed unless manufacturers that have bet their futures on them, like General Motors and VW, invest in or coordinate on a robust supercharger network. These are the observations in an in-depth study of the industry by management professors at the University of California, Davis, and Dartmouth College.

The researchers explain that big ...

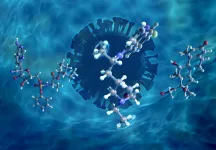

As the scientific community continues researching the novel coronavirus, experts are developing new drugs and repurposing existing ones in hopes of identifying promising candidates for treating symptoms of COVID-19.

Scientists can analyze the molecular dynamics of drug molecules to better understand their interactions with target proteins in human cells and their potential for treating certain diseases. Many studies examine drug molecules in their dry, powder form, but less is known about how such molecules behave in a hydrated environment, which is characteristic of human cells.

Using neutron experiments and computer ...

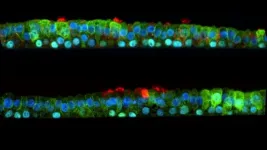

University of Queensland researchers have discovered a new 'seeding' process in brain cells that could be a cause of dementia and Alzheimer's disease.

UQ's Queensland Brain Institute dementia researcher Professor Jürgen Götz said the study revealed that tangled neurons, a hallmark sign of dementia, form in part by a cellular process that has gone astray and allows a toxic protein, tau, to leak into healthy brain cells.

"These leaks create a damaging seeding process that causes tau tangles and ultimately lead to memory loss and other impairments," Professor Götz said.

Professor Götz said until now researchers did not understand how tau seeds were able to escape after ...

Research into a new drug which primes the immune system in the respiratory tract and is in development for COVID-19 shows it is also effective against rhinovirus. Rhinovirus is the most common respiratory virus, the main cause of the common cold and is responsible for exacerbations of chronic respiratory diseases such as asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. In a study recently published in the European Respiratory Journal (LINK), the drug, known as INNA-X, is shown to be effective in a pre-clinical infection model and in human airway cells.

Treatment with INNA-X prior to infection with rhinovirus significantly reduced viral load and inhibited harmful inflammation.

University of Newcastle and Hunter Medical Research Institute (HMRI) researcher Associate Professor ...