(Press-News.org) The mesmerizing flow of a sidewinder moving obliquely across desert sands has captivated biologists for centuries and has been variously studied over the years, but questions remained about how the snakes produce their unique motion. Sidewinders are pit vipers, specifically rattlesnakes, native to the deserts of the southwestern United State and adjacent Mexico.

Scientists had already described the microstructure of the skin on the ventral, or belly, surface of snakes. Many of the snakes studied, including all viper species, had distinctive rearward facing "microspicules" (micron-sized protrusions on scales) that had been interpreted in the context of reducing friction in the forward direction--the direction the crawling snake--and increasing friction in the backward direction to reduce slip.

Considered through the lens of a sidewinder's peculiar form of locomotion, however, it seemed that these microspicules would not function in the same manner. But no one had examined the microstructure of sidewinders, nor of a handful of unrelated African vipers that also sidewind.

Working with naturally-shed skins collected from snakes in zoos, researchers used atomic force microscopy to visualize and measure the microstructures of these scale protrusions in three species of sidewinding vipers as well as many other viper species for comparison. The results of the research, published this week in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, found that indeed the sidewinders have a unique structure distinct from other snakes.

The microspicules were absent in the African sidewinding species and reduced to tiny nubbins in the North American sidewinder. All three snakes also had distinctive crater-like micro-depressions producing a distinctive texture not seen in other snakes.

Daniel Goldman, Dunn Family Professor of Physics at the Georgia Institute of Technology, and Jennifer Rieser, working as a postdoctoral researcher in Goldman's group and currently an assistant professor in the Department of Physics at Emory University, developed mathematical models to test how both the typical texture of rearward-directed microspicules and spicule-less cratered texture function as snakes interact with the ground. The models revealed that the microspicules would actually impede sidewinding, explaining their evolutionary loss in these species.

The models also revealed an unexpected result that microspicules function to improve performance of snakes that use lateral undulation to move. Lateral undulation is the typical side-to-side mode locomotion used by the majority of snake species. "This discovery adds a new dimension to our knowledge of the functionality of these structures, that is more complex than the previous ideas," said Joseph Mendelson, director of research at Zoo Atlanta and adjunct associate professor in the Georgia Tech School of Biological Sciences.

The models indicate that the microspicules act a bit like corduroy fabric. "Friction is low when you run your finger along the length of the furrowed fabric--consistent with previous work--but the furrows produce significant friction when you move your finger sideways across the fabric texture," said Goldman. The functionality of the distinct craters remains a mystery.

The findings could be important to the development of future generations of robots able to move across challenging surfaces such as loose sand. "Understanding how and why this example of convergent evolution works may allow us to adapt it for our own needs, such as building robots that can move in challenging environments," Rieser said.

In terms of anatomy, this was a classic example of convergent evolution between a pair of snake species in Africa and a very distantly related snake in North America, Mendelson noted. Biogeographic reconstructions conducted by Jessica Tingle, a doctoral student at University of California Riverside, indicated that the African snakes are evolutionarily much older than the North American sidewinder, suggesting that the sidewinders represented an earlier phase in adaptation for sidewinding.

Tai-De Li, then at Georgia Tech in the lab of Prof Elisa Riedo and now at the City University of New York, did the AFM measurements.

Drawing from the fields of evolutionary biology, living systems physics, and mathematical modelling, the team produced a study that explains some aspects of what these microstructures on the bellies of snakes do and how they evolved in snakes.

"Our results highlight how an integrated approach can provide quantitative predictions for structure-function relationships and insights into behavioral and evolutionary adaptions in biological systems," the authors wrote.

INFORMATION:

This research was supported by the Georgia Tech Elizabeth Smithgall Watts Fund; National Science Foundation Physics of Living Systems Grants PHY-1205878 and PHY-1150760; and Army Research Office Grant W911NF-11-1-0514. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the sponsoring agencies.

CITATION: Jennifer M. Rieser, Tai-De Li, Jessica L. Tingle, Daniel I. Goldman, and Joseph R. Mendelson III, "Functional consequences of convergently evolved microscopic skin features on snake locomotion." (Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 2021)

PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] -- Studies have shown that nearly half of all medical students in the U.S. report symptoms of burnout, a long-term reaction to stress characterized by emotional exhaustion, cynicism and feelings of decreased personal accomplishment. Beyond the personal toll, the implications for aspiring and practicing physicians can be severe, from reduced quality of care to increased risk of patient safety incidents.

According to a new study published on Tuesday, Feb. 2, in JAMA Network Open, students who identify as lesbian, gay or bisexual ...

Period poverty, a lack of access to menstrual hygiene products, and other unmet menstrual health needs can have far-reaching consequences for women and girls in the United States and globally.

New research led by George Mason University's College of Health and Human Services found that more than 14% of college women experienced period poverty in the past year, and 10% experienced period poverty every month. Women who experienced period poverty every month (68%) or in the past year (61.2%) were more likely to experience moderate or severe depression than those who did not experience period poverty (43%).

Dr. Jhumka Gupta, an associate professor at George Mason University was senior author of the study published in BMC Women's Health. ...

MINNEAPOLIS- February 2, 2021 - In Minnesota, there are currently about END ...

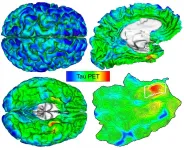

BOSTON - Amyloid-beta and tau are the two key abnormal protein deposits that accumulate in the brain during the development of Alzheimer's disease, and detecting their buildup at an early stage may allow clinicians to intervene before the condition has a chance to take hold. A team led by investigators at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) has now developed an automated method that can identify and track the development of harmful tau deposits in a patient's brain. The research, which is published in END ...

Nearly 11 percent of people admitted to an intensive care unit in Sweden between 2010 and 2018 received opioid prescriptions on a regular basis for at least six months and up to two years after discharge. That is according to a study by researchers at Karolinska Institutet published in Critical Care Medicine. The findings suggest some may become chronic opioid users despite a lack of evidence of the drugs' long-term effectiveness and risks linked to increased mortality.

"We know that the sharp rise in opioid prescriptions in the U.S. has contributed to a deadly opioid crisis there," says first author Erik von Oelreich, PhD student in the Department of Physiology and ...

A decision-support tool that could be accessed via mobile devices may help clinicians in lower-resource settings avoid unnecessary antibiotic prescriptions for children with diarrhoea, a study published today in eLife shows.

The preliminary findings suggest that incorporating real-time environmental, epidemiologic, and clinical data into an easy-to-access, electronic tool could help clinicians appropriately treat children with diarrhoea even when testing is not available. This could help avoid the overuse of antibiotics, which contributes to the emergence of drug-resistant bacteria.

"Diarrhoea is a common condition among children ...

FRANKFURT. Chronic liver disease and even cirrhosis can go unnoticed for a long time because many patients have no symptoms: the liver suffers silently. When the body is no longer able to compensate for the liver's declining performance, the condition deteriorates dramatically in a very short time: tissue fluid collects in the abdomen (ascites), internal bleeding occurs in the oesophagus and elsewhere, and the brain is at risk of being poisoned by metabolic products. This acute decompensation of liver cirrhosis can develop into acute-on-chronic liver failure with inflammatory reactions throughout the body and failure of several organs.

In the PREDICT study, led ...

BLOOMINGTON, Ind. - In Lily Tomlin's classic SNL comedy sketch, her telephone operator "Ernestine" famously delivers the punchline, "We don't care. We don't have to. We're the Phone Company." But new research finds that satisfied customers mean increased profits even for public utilities that don't face competition.

Little is known about effect of customer satisfaction at utilities. As a result, utility managers are often unsure how much to invest in customer service - if anything at all. The issue also is of interest to regulators responsible for protecting consumers.

The study, in ...

CORVALLIS, Ore. - One of birdwatching's most commonly held and colorfully named beliefs, the Patagonia Picnic Table Effect, is more a fun myth than a true phenomenon, Oregon State University research suggests.

Owing its moniker to an Arizona rest area, the Patagonia Picnic Table Effect, often shortened to PPTE, has for decades been cited as a key driver of behavior, and rare-species-finding success, among participants in the multibillion-dollar recreational birding business - an industry that has gotten even stronger during a pandemic that's shut down so many other activities.

But a study led by an OSU College of Science ...

Scientists and engineers at the University of Sydney and Microsoft Corporation have opened the next chapter in quantum technology with the invention of a single chip that can generate control signals for thousands of qubits, the building blocks of quantum computers.

"To realise the potential of quantum computing, machines will need to operate thousands if not millions of qubits," said Professor David Reilly, a designer of the chip who holds a joint position with Microsoft and the University of Sydney.

"The world's biggest quantum computers currently operate with just 50 or so qubits," he said. "This small scale is partly because of limits to the physical architecture that control the qubits."

"Our ...