Scientists advocate breaking laws - of geography and ecology

2021-02-02

(Press-News.org) Recent global calamities - the pandemic, wildfires, floods - are spurring interdisciplinary scientists to nudge aside the fashionable First Law of Geography that dictates "everything is related to everything else, but near things are more related than distant things."

Geography, and by association, ecology, has largely followed what's known as Tobler's Law, which took hold in the early 1970s. But then came the novel coronavirus apparently has leapt from wildlife meat markets in China to the world in a matter of months. Global climate change creates conditions ripe for infernos in the North American west and Australia. Extreme Ohio flooding in 2018 gave way to sediments and excessive nutrients to dump into the Gulf of Mexico to the tune of some 300 square kilometers.

In other words, all that's local is a lot more global, and the scientists in this week's Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment say solutions can only be found through broader views and collaborations nearby and far away.

"Understanding and finding solutions to the recent and future crises need an integrated framework across local to global scales," said Jianguo "Jack" Liu, Michigan State University's (MSU) Rachel Carson Chair in Sustainability.

Liu has introduced the framework of metacoupling, which allows scientists to view the world as it truly is - with humans and nature interacting over space and time and without boundaries of academic disciplines. The metacoupling framework lets scientists understand how actions locally, nearby and far away - like policies that regulate the sale of wild animals or affect the release of greenhouse gasses - result more in just cause and effect. Actions bounce back and forth between humans and nature from the community nearby and the country on the other side of the world. These are examples of feedback, and there are impacts that spill over in between. The paper notes that the metacoupling inserts the human element into the equation - both where events happen, and where our impact is felt, and the spaces in between.

In other words, for much of environmental sciences, Tobler's Law and its geography focus is going the way of tube tops and tie-dye in favor of what the authors say is "a more comprehensive understanding of human-natural systems will emerge through this approach as a requisite for addressing today's large-scale ecological problems, and this will be part of the "evolution" of the new field of macrosystems biology."

Lead author Flavia Tromboni says the paper delivers a message that science indeed must evolve to capture the world as it is - and where it is going. "We cannot capture the magnitude of human impacts globally and be able to find solutions for pressing global environmental issues without considering all these multi-scale interactions," she said. Tromboni is a research assistant professor in the Global Water Center of the University of Nevada, Reno.

Other authors of "Macrosystems as metacoupled human and natural systems" note the issues keep unfolding. Kyla Dahlin, an assistant professor in MSU's Department of Geography, Environment, and Spatial Sciences, points out today's western wildfires already are leading to questions about crops - and ultimately grocery store prices -hundreds of miles away. "Metacoupling especially breaks with the idea of Tobler's Law," she said.

INFORMATION:

In addition to Liu, Tromboni and Dahlin, the paper was written by Emanuele Ziaco, David Breshears, Kimberly Thompson, Water Dodds, Elizabeth La Rue, James Thorpe, Andrés Viña, Maysa Laguë, Alain Maasri, Hongbo Yang, Sudeep Chandra and Songlin Fei.

The work is supported by the National Science Foundation and AgBioResearch.

[Attachments] See images for this press release:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-02-02

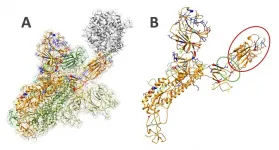

EL PASO, Texas - An effort led by Lin Li, Ph.D., assistant professor of physics at The University of Texas at El Paso, in collaboration with students and faculty from Howard University, has identified key variants that help explain the differences between the viruses that cause COVID-19 and Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS).

A team comprised of researchers from UTEP and the historically Black research university in Washington, D.C., discovered valuable data in comparing the fundamental mechanisms of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (SARS-CoV) and SARS-CoV-2 -- also known as COVID-19 -- to better understand how ...

2021-02-02

CORVALLIS, Ore. - Extensive sea ice covered the world's oceans during the last ice age, which prevented oxygen from penetrating into the deep ocean waters, complicating the relationship between oxygen and carbon, a new study has found.

"The sea ice is effectively like a closed window for the ocean," said Andreas Schmittner, a climate scientist at Oregon State University and co-author on the paper. "The closed window keeps fresh air out; the sea ice acted as a barrier to keep oxygen from entering the ocean, like stale air in a room full of people. If you open the window, oxygen ...

2021-02-02

Amazon's search algorithm gives preferential treatment to books that promote false claims about vaccines, according to research by UW Information School Ph.D. student Prerna Juneja and Assistant Professor Tanu Mitra.

Meanwhile, books that debunk health misinformation appear lower in Amazon's search results, where they are less likely to be seen, the researchers wrote in a paper that was recently accepted to CHI, the top annual conference on human-computer interaction.

In their paper, Juneja and Mitra noted that Amazon has faced criticism for not regulating health-related products on its platform. They conducted audits to determine how much health misinformation is present in Amazon's recommendations ...

2021-02-02

The lockdowns and reduced societal activity related to the COVID-19 pandemic affected emissions of pollutants in ways that slightly warmed the planet for several months last year, according to new research led by the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR).

The counterintuitive finding highlights the influence of airborne particles, or aerosols, that block incoming sunlight. When emissions of aerosols dropped last spring, more of the Sun's warmth reached the planet, especially in heavily industrialized nations, such as the United States and Russia, that normally pump high amounts of aerosols into the atmosphere.

"There was a big decline in emissions from the most polluting industries, and that had immediate, short-term effects on temperatures," said ...

2021-02-02

Yale researchers are developing a skin cancer treatment that involves injecting nanoparticles into the tumor, killing cancer cells with a two-pronged approach, as a potential alternative to surgery.

The results are published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

"For a lot of patients, treating skin cancer is much more involved than it would be if there was a way to effectively treat them with a simple procedure like an injection," said Dr. Michael Girardi, professor and vice chair of dermatology at Yale School of Medicine and senior author of the study. "That's always been a holy grail in dermatology -- to find a simpler way to treat skin cancers such as basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma."

For the treatment, tumors are injected ...

2021-02-02

A new study from scientists of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Biology in Plön, Germany, and the Chinese Academy of Sciences in Beijing shows that the potential genetic burden of mutations arising from retrogenes is significantly greater than originally thought.

Genetic information is stored in DNA and transcribed as mRNA. The mRNA is usually translated into proteins. However, it has long been known that mRNA can also be reverse transcribed to DNA and integrated back into the genome. Such cases are referred to as retrogenes. In an article, a team from the Max Planck Institute for ...

2021-02-02

When different groups of people come into contact, what's the key to motivating advantaged racial groups to join historically disadvantaged racial minority groups to strive for racial equality and social justice? It's a complex conundrum studied for years by social scientists like Linda Tropp, professor of social psychology at the University of Massachusetts Amherst.

Her latest research, published in the International Journal of Intercultural Relations, tested and supported Tropp and colleagues' proposition that having open communication about group differences is a crucial pathway.

While greater contact between racial groups is typically associated with less ...

2021-02-02

New drivers between the ages of 15 and 25 account for nearly half of the more than one million road deaths that occur worldwide each year, according to the World Health Organization. Educational programs often use fear-based messaging and films of crash scenes to reduce risky driving behavior among young people. But does this "scary" approach work?

A new study published in the journal Risk Analysis suggests that fear-based messaging fails to reduce risky driving behavior, while fear-based Virtual Reality (VR) films depicting a violent collision may actually lead young drivers to take more chances behind the wheel.

A team of psychologists led by University of Antwerp researcher Clara Alida Cutello, PhD, conducted a study of 146 students ...

2021-02-02

Are Gut Microbes the Key to Unlocking Anxiety

A mouse study suggests the genetic contribution to anxiety is partially mediated by the gut microbiome

By Greta Lorge

The prevalence of anxiety disorders, already the most common mental illness in many countries, including the U.S., has surged during the novel coronavirus pandemic. A study led by researchers in Berkeley Lab's Biosciences Area provides evidence that taking care of our gut microbiome may help mitigate some of that anxiety.

The team used a genetically heterogeneous lineage of mice known as the Collaborative Cross (CC) to probe connections among genes, gut microbiome ...

2021-02-02

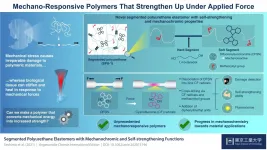

A fascinating and crucial ability of biological tissue, such as muscle, is self-healing and self-strengthening in response to damage caused by external forces. Most human-made polymers, on the other hand, break irreversibly under enough mechanical stress, which makes them less useful for certain critical applications like manufacturing artificial organs. But what if we could design polymers that reacted chemically to mechanical stimuli and used this energy to enhance their properties?

This goal, which has proven to be a big challenge, is under the spotlight in the field of mechanochemistry. In a recent study published in Angewandte Chemie ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Scientists advocate breaking laws - of geography and ecology