(Press-News.org) CAMBRIDGE, MA -- Twenty years ago this month, the first draft of the human genome was publicly released. One of the major surprises that came from that project was the revelation that only 1.5 percent of the human genome consists of protein-coding genes.

Over the past two decades, it has become apparent that those noncoding stretches of DNA, originally thought to be "junk DNA," play critical roles in development and gene regulation. In a new study published today, a team of researchers from MIT has published the most comprehensive map yet of this noncoding DNA.

This map provides in-depth annotation of epigenomic marks -- modifications indicating which genes are turned on or off in different types of cells -- across 833 tissues and cell types, a significant increase over what has been covered before. The researchers also identified groups of regulatory elements that control specific biological programs, and they uncovered candidate mechanisms of action for about 30,000 genetic variants linked to 540 specific traits.

"What we're delivering is really the circuitry of the human genome. Twenty years later, we not only have the genes, we not only have the noncoding annotations, but we have the modules, the upstream regulators, the downstream targets, the disease variants, and the interpretation of these disease variants," says Manolis Kellis, a professor of computer science, a member of MIT's Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory and of the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, and the senior author of the new study.

MIT graduate student Carles Boix is the lead author of the paper, which appears today in Nature. Other authors of the paper are MIT graduate students Benjamin James and former MIT postdocs Yongjin Park and Wouter Meuleman, who are now principal investigators at the University of British Columbia and the Altius Institute for Biomedical Sciences, respectively. The researchers have made all of their data publicly available for the broader scientific community to use.

Epigenomic control

Layered atop the human genome -- the sequence of nucleotides that makes up the genetic code -- is the epigenome. The epigenome consists of chemical marks that help determine which genes are expressed at different times, and in different cells. These marks include histone modifications, DNA methylation, and how accessible a given stretch of DNA is.

"Epigenomics directly reads the marks used by our cells to remember what to turn on and what to turn off in every cell type, and in every tissue of our body. They act as post-it notes, highlighters, and underlining," Kellis says. "Epigenomics allows us to peek at what each cell marked as important in every cell type, and thus understand how the genome actually functions."

Mapping these epigenomic annotations can reveal genetic control elements, and the cell types in which different elements are active. These control elements can be grouped into clusters or modules that function together to control specific biological functions. Some of these elements are enhancers, which are bound by proteins that activate gene expression, while others are repressors that turn genes off.

The new map, EpiMap (Epigenome Integration across Multiple Annotation Projects), builds on and combines data from several large-scale mapping consortia, including ENCODE, Roadmap Epigenomics, and Genomics of Gene Regulation.

The researchers assembled a total of 833 biosamples, representing diverse tissues and cell types, each of which was mapped with a slightly different subset of epigenomic marks, making it difficult to fully integrate data across the multiple consortia. They then filled in the missing datasets, by combining available data for similar marks and biosamples, and used the resulting compendium of 10,000 marks across 833 biosamples to study gene regulation and human disease.

The researchers annotated more than 2 million enhancer sites, covering only 0.8 percent of each biosample, and collectively 13 percent of the genome. They grouped them into 300 modules based on their activity patterns, and linked them to the biological processes they control, the regulators that control them, and the short sequence motifs that mediate this control. The researchers also predicted 3.3 million links between control elements and the genes that they target based on their coordinated activity patterns, representing the most complete circuitry of the human genome to date.

Disease links

Since the final draft of the human genome was completed in 2003, researchers have performed thousands of genome-wide association studies (GWAS), revealing common genetic variants that predispose their carriers to a particular trait or disease.

These studies have yielded about 120,000 variants, but only 7 percent of these are located within protein-coding genes, leaving 93 percent that lie in regions of noncoding DNA.

How noncoding variants act is extremely difficult to resolve, however, for many reasons. First, genetic variants are inherited in blocks, making it difficult to pinpoint causal variants among dozens of variants in each disease-associated region. Moreover, noncoding variants can act at large distances, sometimes millions of nucleotides away, making it difficult to find their target gene of action. They are also extremely dynamic, making it difficult to know which tissue they act in. Lastly, understanding their upstream regulators remains an unsolved problem.

In this study, the researchers were able to address these questions and provide candidate mechanistic insights for more than 30,000 of these noncoding GWAS variants. The researchers found that variants associated with the same trait tended to be enriched in specific tissues that are biologically relevant to the trait. For example, genetic variants linked to intelligence were found to be in noncoding regions active in the brain, while variants associated with cholesterol level are in regions active in the liver.

The researchers also showed that some traits or diseases are affected by enhancers active in many different tissue types. For example, they found that genetic variants associated with coronary heart disease (CAD) were active in adipose tissue, coronary arteries, and the liver, among many other tissues.

Kellis' lab is now working with diverse collaborators to pursue their leads in specific diseases, guided by these genome-wide predictions. They are profiling heart tissue from patients with coronary artery disease, microglia from Alzheimer's patients, and muscle, adipose, and blood from obesity patients, which are predicted mediators of these disease based on the current paper, and his lab's previous work.

Many other labs are already using the EpiMap data to pursue studies of diverse diseases. "We hope that our predictions will be used broadly in industry and in academia to help elucidate genetic variants and their mechanisms of action, help target therapies to the most promising targets, and help accelerate drug development for many disorders," Kellis says.

INFORMATION:

The research was funded by the National Institutes of Health.

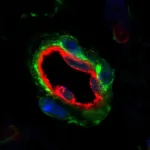

DALLAS - Feb. 3, 2021 - Gaining more fat cells is probably not what most people want, although that might be exactly what they need to fight off diabetes and other diseases. How and where the body can add fat cells has remained a mystery - but two new studies from UT Southwestern provide answers on the way this process works.

The studies, both published online today in Cell Stem Cell, describe two different processes that affect the generation of new fat cells. One reports how fat cell creation is impacted by the level of activity in tiny organelles inside cells called mitochondria. The other outlines a process that prevents new fat cells from developing in one fat storage area in ...

People with severe mental disorders have a significantly increased risk of dying from COVID-19. This has been shown in a new study from Umeå University and Karolinska Institutet in Sweden. Among the elderly, the proportion of deaths due to COVID-19 was almost fourfold for those with severe mental disorders compared to non-mentally ill people in the same age.

"We see a high excess mortality due to COVID-19 among the elderly with severe mental disorders, which gives us reason to consider whether this group should be given priority for vaccines," says Martin Maripuu, associate professor at Umeå University.

In the current study, the researchers studied data covering the entire Swedish population over the age of 20 during the period from 11 March to 15 June 2020. Among citizens ...

CABI scientists have updated the first major study of potential biological controls that could be used in the fight against the devastating fall armyworm in Africa. The research offers new insight into evidence of their efficacy in the field and increased availability as commercial products.

Indeed, the review, published in the Journal of Applied Entomology, includes many biocontrol products which are now featured in the CABI BioProtection Portal - a free web-based tool that enables users to discover information about registered biocontrol and biopesticide products around the world.

The fall armyworm ...

The behavior of the solvated electron e-aq has fundamental implications for electrochemistry, photochemistry, high-energy chemistry, as well as for biology--its nonequilibrium precursor is responsible for radiation damage to DNA--and it has understandably been the topic of experimental and theoretical investigation for more than 50 years.

Though the hydrated electron appears to be simple--it is the smallest possible anion as well as the simplest reducing agent in chemistry--capturing its physics is...hard. They are short lived and generated in small quantities and so impossible to concentrate and isolate. Their structure is therefore impossible to capture with direct experimental observation such as diffraction methods or NMR. Theoretical modelling has turned out to ...

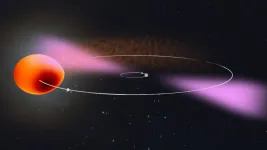

An international research team including members from The University of Manchester has shown that a rapidly rotating neutron star is at the core of a celestial object now known as PSR J2039?5617

The international collaboration used novel data analysis methods and the enormous computing power of the citizen science project Einstein@Home to track down the neutron star's faint gamma-ray pulsations in data from NASA's Fermi Space Telescope. Their results show that the pulsar is in orbit with a stellar companion about a sixth of the mass of our Sun. The pulsar is slowly but surely evaporating this star. The team also found that the companion's orbit varies slightly and unpredictably over time. Using their search ...

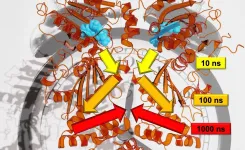

Consider for a moment a tree swaying in the wind. How long does it take for the movement of a twig to reach the trunk of the tree? How is this motion actually transmitted through the tree? Researchers at the University of Freiburg are transferring this kind of question to the analysis of proteins - which are the molecular machinery of cells. A team of researchers lead by Prof. Dr. Thorsten Hugel of the Institute of Physical Chemistry, and Dr. Steffen Wolf and Prof. Dr. Gerhard Stock of the Institute of Physics are investigating how the signals that cause structural changes in proteins travel from one site to another. They are also trying to ...

Washington, DC / New Delhi, India - Researchers at CDDEP have released, The State of the World's Antibiotics in 2021, which presents extensive data on global antimicrobial use and resistance as well as drivers and correlates of antimicrobial resistance, based on CDDEP's extensive research and data collection through ResistanceMap, a global repository that has been widely used by researchers, policymakers, and the media.

Since the first State of the World's Antibiotics report in 2015, antimicrobial resistance has leveled off in some high-income countries but continues to rise in many low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), where access to antibiotics has risen with increases in gross ...

Researchers have found new evidence that global warming is affecting the size of commercial fish species, documenting for the first time that juvenile fish are getting bigger, as well as confirming that adult fish are getting smaller as sea temperatures rise. The findings are published in the British Ecological Society's Journal of Applied Ecology.

The researchers from the University of Aberdeen looked at four of the most important commercial fish species in the North Sea and the West of Scotland: cod, haddock, whiting and saithe. They found that juvenile fish in the North Sea and on the West of Scotland have been getting bigger while adult fish have been getting smaller. These changes ...

The world's largest bird, the ostrich, has problems reproducing when the temperature deviates by 5 degrees or more from the ideal temperature of 20 °C. The research, from Lund University in Sweden, is published in Nature Communications.

The results show that the females lay up to 40 percent fewer eggs if the temperature has fluctuated in the days before laying eggs. Both male and female production of gametes is also negatively affected.

"Many believe that ostriches can reproduce anywhere, but they are actually very sensitive to changes in temperature. Climate change means that temperatures will fluctuate even more, and that could be a challenge for the ostrich", says Mads Schou, researcher at Lund ...

Mothers are at increased risk of mental health problems as they struggle to balance the demands of childcare and remote working in COVID-19 lockdowns, according to new research from an international team of researchers.

The findings, published in the journal Psychological Medicine, were drawn from a comprehensive, online survey of mothers in China, Italy and the Netherlands.

Changes to their working lives, family strife and loss of social networks emerged as common factors affecting the mental health of mothers in all three countries.

The study was carried out by a team from Radboud University, ...