(Press-News.org) Mechanism for control of antibiotic production in soil bacteria is visualised for the first time by scientists at University of Warwick and Monash University

Research reported in Nature could lead to improved manufacturing of existing antibiotics, and open up opportunities to discover new ones

The majority of clinically used antibiotics are derived from soil bacteria, but can be hard to find because their production is switched off in laboratory cultures

The discovery of how hormone-like molecules turn on antibiotic production in soil bacteria could unlock the untapped opportunities for medicines that are under our very feet.

An international team of scientists working at the University of Warwick, UK, and Monash University, Australia, have determined the molecular basis of a biological mechanism that could enable more efficient and cost-effective production of existing antibiotics, and also allow scientists to uncover new antibiotics in soil bacteria.

It is detailed in a new study published today (3 February) in the journal Nature.

Most clinically used antibiotics are molecules produced by micro-organisms such as bacteria. The majority of these are soil bacteria called Actinobacteria, which are cultivated in the laboratory to allow the molecules they produce to be extracted. However, the production of these molecules is frequently switched off in laboratory cultures, making them difficult to find.

The bacteria tightly control the production of their antibiotics using small molecules akin to hormones. The team at Warwick and Monash investigated a specific class of these bacterial hormones that they had previously discovered, termed 2-akyl-4-hydroxymethylfuran-3-carboxylic acids or AHFCAs, to find out what role they played in controlling the production of an antibiotic in the Actinobacterium Streptomyces coelicolor.

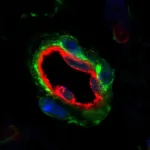

Using x-ray crystallography and single-particle cryo-electron microscopy techniques, they analysed the structure of a protein, known as a transcription factor, bound to a particular region of DNA from the bacterium. This prevents the bacterium from producing the antibiotic.

They then determined the structure of the transcription factor with a synthesized version of one of the AHFCA hormones bound to it, which showed how the DNA is released and antibiotic production is switched on.

Joint lead author Dr Chris Corre, Associate Professor of Synthetic Biology at the University of Warwick Departments of Life Sciences & Chemistry, said: "Antibiotic resistance is becoming a major issue and we urgently need new antibiotics to tackle it.

"We already know that similar processes control the production of a lot of commercially important molecules. If we understand the mechanisms that control the production of these compounds, we can improve the process, to make it more economically viable.

"It turned out that although we were only looking at one particular class of hormones, the mechanism we found appears to be conserved across all of the different hormone classes in Actinobacteria."

Actinobacteria are more complicated than conventional bacteria. They are generally not motile like other forms of bacteria and they have a complex development cycle that the production of the antibiotics is integrated into.

However, when grown in pure culture these bacteria will often switch off antibiotic production, confounding scientists' efforts to study them. By understanding the molecular mechanism for how this process is controlled, scientists can switch on the production of new antibiotics that are not produced in laboratory cultures.

Dr Corre adds: "We can use these strategies to turn on production of new antibiotics in Actinobacteria. Among them, we'd hope to find some that could be useful for tackling infections caused by resistant microbes, as well as other diseases. These compounds would be hard to find via traditional processes."

Key to the discovery was determining the structure of the complex of the transcription factor bound to the DNA, which required the use of single particle cryo-electron microscopy facilities at Monash University to overcome challenges with x-ray crystallography.

Professor Greg Challis, who co-led the study and has a joint appointment at the University of Warwick Department of Chemistry and Monash University, said: "Only a modest number of structures of this type of protein-DNA complex have been determined using x-ray crystallography over the last few decades due to the challenge of obtaining suitable crystals. By using cryo-electron microscopy we have circumvented this challenge, which should make it easier to determine the structures of similar complexes in the future. It wouldn't have been possible to illuminate the molecular basis for control of antibiotic production by these hormones without the combined expertise of colleagues at Warwick and Monash."

INFORMATION:

Established in 2012, the award-winning Monash Warwick Alliance brings together two research-intensive institutions, of a similar age and global reputation, to form a pioneering model for global higher education partnerships - one that is fully integrated into every layer of university life, going far beyond standard collaborative agreements in the sector.

From co-published interdisciplinary research, to joint innovations in teaching and learning, vastly increased international mobility for members of the Alliance community, and shared practice throughout professional services, the Alliance has been co-developed from its inception by colleagues on both campuses, combining the different complementary strengths of each institution.

* 'Molecular basis for control of antibiotic production by a bacterial hormone' will be published in Nature, DOI: 10.1038/s41586-021-03195-x

Link: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-021-03195-x (to go live when embargo lifts)

* This research received support from the Royal Society and the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council, part of UK Research and Innovation.

Notes to editors:

Download an image of Streptomyces coelicolor bacteria:

https://warwick.ac.uk/services/communications/medialibrary/images/january_2021/streptomyces_coelicolor_corre_glc_edit.jpg

Caption: The soil-dwelling Streptomyces coelicolor bacteria producing antibiotics in a Petri dish.

Credit: Christophe Corre

For interviews or a copy of the paper contact:

Peter Thorley

Media Relations Manager

(Warwick Medical School and Department of Physics) | Press & Media Relations | University of Warwick

Email: peter.thorley@warwick.ac.uk

Mob: +44 (0) 7824 540863

ANN ARBOR, Mich. - The suicide rate among American adolescents has rose drastically over the last decade, but many at-risk youths aren't receiving the mental health services they need.

In fact, one of the greatest challenges is identifying the young people who need the most help.

Now, researchers have developed a personalized system to better detect suicidal youths. The novel, universal screening tool helps caregivers reliably predict an adolescent's suicide risk - alerting them to which ones need follow-up interventions - according to Michigan Medicine-led findings published in JAMA Psychiatry.

"Too many young people are dying by suicide and many at high risk go completely unrecognized and untreated," says lead author Cheryl King, Ph.D., ...

CAMBRIDGE, MA -- Twenty years ago this month, the first draft of the human genome was publicly released. One of the major surprises that came from that project was the revelation that only 1.5 percent of the human genome consists of protein-coding genes.

Over the past two decades, it has become apparent that those noncoding stretches of DNA, originally thought to be "junk DNA," play critical roles in development and gene regulation. In a new study published today, a team of researchers from MIT has published the most comprehensive map yet of this noncoding DNA.

This map provides in-depth annotation of epigenomic marks -- modifications indicating which genes are turned on or off in different types of cells -- across 833 tissues and cell types, a significant increase over ...

DALLAS - Feb. 3, 2021 - Gaining more fat cells is probably not what most people want, although that might be exactly what they need to fight off diabetes and other diseases. How and where the body can add fat cells has remained a mystery - but two new studies from UT Southwestern provide answers on the way this process works.

The studies, both published online today in Cell Stem Cell, describe two different processes that affect the generation of new fat cells. One reports how fat cell creation is impacted by the level of activity in tiny organelles inside cells called mitochondria. The other outlines a process that prevents new fat cells from developing in one fat storage area in ...

People with severe mental disorders have a significantly increased risk of dying from COVID-19. This has been shown in a new study from Umeå University and Karolinska Institutet in Sweden. Among the elderly, the proportion of deaths due to COVID-19 was almost fourfold for those with severe mental disorders compared to non-mentally ill people in the same age.

"We see a high excess mortality due to COVID-19 among the elderly with severe mental disorders, which gives us reason to consider whether this group should be given priority for vaccines," says Martin Maripuu, associate professor at Umeå University.

In the current study, the researchers studied data covering the entire Swedish population over the age of 20 during the period from 11 March to 15 June 2020. Among citizens ...

CABI scientists have updated the first major study of potential biological controls that could be used in the fight against the devastating fall armyworm in Africa. The research offers new insight into evidence of their efficacy in the field and increased availability as commercial products.

Indeed, the review, published in the Journal of Applied Entomology, includes many biocontrol products which are now featured in the CABI BioProtection Portal - a free web-based tool that enables users to discover information about registered biocontrol and biopesticide products around the world.

The fall armyworm ...

The behavior of the solvated electron e-aq has fundamental implications for electrochemistry, photochemistry, high-energy chemistry, as well as for biology--its nonequilibrium precursor is responsible for radiation damage to DNA--and it has understandably been the topic of experimental and theoretical investigation for more than 50 years.

Though the hydrated electron appears to be simple--it is the smallest possible anion as well as the simplest reducing agent in chemistry--capturing its physics is...hard. They are short lived and generated in small quantities and so impossible to concentrate and isolate. Their structure is therefore impossible to capture with direct experimental observation such as diffraction methods or NMR. Theoretical modelling has turned out to ...

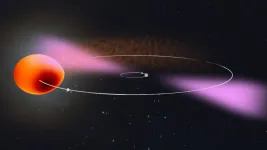

An international research team including members from The University of Manchester has shown that a rapidly rotating neutron star is at the core of a celestial object now known as PSR J2039?5617

The international collaboration used novel data analysis methods and the enormous computing power of the citizen science project Einstein@Home to track down the neutron star's faint gamma-ray pulsations in data from NASA's Fermi Space Telescope. Their results show that the pulsar is in orbit with a stellar companion about a sixth of the mass of our Sun. The pulsar is slowly but surely evaporating this star. The team also found that the companion's orbit varies slightly and unpredictably over time. Using their search ...

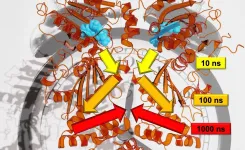

Consider for a moment a tree swaying in the wind. How long does it take for the movement of a twig to reach the trunk of the tree? How is this motion actually transmitted through the tree? Researchers at the University of Freiburg are transferring this kind of question to the analysis of proteins - which are the molecular machinery of cells. A team of researchers lead by Prof. Dr. Thorsten Hugel of the Institute of Physical Chemistry, and Dr. Steffen Wolf and Prof. Dr. Gerhard Stock of the Institute of Physics are investigating how the signals that cause structural changes in proteins travel from one site to another. They are also trying to ...

Washington, DC / New Delhi, India - Researchers at CDDEP have released, The State of the World's Antibiotics in 2021, which presents extensive data on global antimicrobial use and resistance as well as drivers and correlates of antimicrobial resistance, based on CDDEP's extensive research and data collection through ResistanceMap, a global repository that has been widely used by researchers, policymakers, and the media.

Since the first State of the World's Antibiotics report in 2015, antimicrobial resistance has leveled off in some high-income countries but continues to rise in many low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), where access to antibiotics has risen with increases in gross ...

Researchers have found new evidence that global warming is affecting the size of commercial fish species, documenting for the first time that juvenile fish are getting bigger, as well as confirming that adult fish are getting smaller as sea temperatures rise. The findings are published in the British Ecological Society's Journal of Applied Ecology.

The researchers from the University of Aberdeen looked at four of the most important commercial fish species in the North Sea and the West of Scotland: cod, haddock, whiting and saithe. They found that juvenile fish in the North Sea and on the West of Scotland have been getting bigger while adult fish have been getting smaller. These changes ...