(Press-News.org) Piezoelectric materials hold great promise as sensors and as energy harvesters but are normally much less effective at high temperatures, limiting their use in environments such as engines or space exploration. However, a new piezoelectric device developed by a team of researchers from Penn State and QorTek remains highly effective at elevated temperatures.

Clive Randall, director of Penn State's Materials Research Institute (MRI), developed the material and device in partnership with researchers from QorTek, a State College, Pennsylvania-based company specializing in smart material devices and high-density power electronics.

"NASA's need was how to power electronics in remote locations where batteries are difficult to access for changing," Randall said. "They also wanted self-powering sensors that monitor systems such as engine stabilities and have these devices work during rocket launches and other high-temperature situations where current piezoelectrics fail due to the heat."

Piezoelectric materials generate an electric charge when rapidly compressed by a mechanical force during vibrations or motion, such as from machinery or an engine. This can serve as a sensor to measure changes in pressure, temperature, strain or acceleration. Potentially, piezoelectrics could power a range of devices from personal electronics like wristband devices to bridge stability sensors.

The team integrated the material into a version of a piezoelectric energy harvester technology called a bimorph that enables the device to act either as a sensor, an energy harvester or an actuator. A bimorph has two piezoelectric layers shaped and assembled to maximize efficient energy harvesting. Sensors and energy harvesters, while bending the bimorph structure, generate an electrical signal for measurement or act as a power source.

Unfortunately, these functions work less-effectively in high-temperature environments. Current state-of-the-art piezoelectric energy harvesters are normally limited to a maximum effective operating temperature range of 176 degrees Fahrenheit (80 degrees Celsius) to 248 degrees Fahrenheit (120 degrees C).

"A fundamental problem with piezoelectric materials is their performance starts to drop pretty significantly at temperatures above 120 C, to the point where above 200 C (392 F) their performance is negligible," Gareth Knowles, chief technical officer of QorTek, said. "Our research demonstrates a possible solution for that for NASA."

The new piezoelectric material composition developed by the researchers showed a near-constant efficient performance at temperatures up to 482 F (250 C). In addition, while there was a gradual drop-off in performance above 482 F (250°C), the material remained effective as an energy harvester or sensor at temperatures to well-above 572 F the researchers reported in the Journal of Applied Physics.

"The compositions performing just as well at these high temperatures as they do at room temperature is a first, as no one has ever managed piezoelectric materials that effectively operate at such high temperatures," Knowles said.

Another benefit of the material was an unexpectedly high level of electricity production. While at present, piezoelectric energy harvesters are not at the level of more efficient power producers such as solar cells, the new material's performance was strong enough to open possibilities for other applications, according to Randall.

"The energy production part of this was very impressive, the material shows record performance efficiencies as a piezoelectric energy harvester," Randall said. "This would potentially enable a continuous, battery-free power supply in dark or concealed environments such as inside an automotive system or even the human body."

Both Randall and Knowles noted that the partnership between Penn State and QorTek, which goes back over 20 years, enabled development of the new, improved piezoelectric material by complementing each other's resources.

"In general, a big benefit of a partnership like this is you can tap into the large knowledge reservoir in the field that MRI and Penn State has and that small companies like ours sometimes do not," Knowles said. "Another benefit is often universities have physical resources such as equipment that again, you won't ordinarily find inside a small company."

Randall noted that since QorTek has many employees who are Penn State alumni, there is a familiarity with both the research subject and the people involved.

"One of my post-doctoral researchers and first author on the paper, Wei-Ting Chen, was hired by QorTek so there was a transfer of expertise in that case," Randall said. "Also, the skillsets offered by QorTek such as mechanical engineering, device design and measurement expertise pushed development at a much faster rate than would be possible given the budget we were given. So the partnership enabled a really fruitful amplification of the project."

INFORMATION:

Along with Randall and Chen, other authors on the paper include from Penn State, Xiao-Ming Chen, MRI research assistant, and from QorTek, Safakcan Tuncdemir, vice president of materials and devices; Ahmet Erkan Gurdal, materials group manager; and Josh Gambal, mechanical design engineer.

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration's Small Business Technology Transfer Program and the National Science Foundation funded this research.

UNIVERSITY PARK, Pa. -- Muscle wasting, or the loss of muscle tissue, is a common problem for people with cancer, but the precise mechanisms have long eluded doctors and scientists. Now, a new study led by Penn State researchers gives new clues to how muscle wasting happens on a cellular level.

Using a mouse model of ovarian cancer, the researchers found that cancer progression led to fewer skeletal muscle ribosomes -- particles in the cell that make proteins. Because muscle mass is mainly determined by protein synthesis, having less ribosomes likely explains why muscles waste away in cancer.

Gustavo Nader, associate professor of kinesiology and physiology at Penn State, said the findings suggest a mechanism for muscle wasting that could be relevant ...

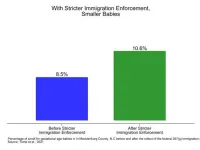

DURHAM, N.C. -- Harsher immigration law enforcement by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement leads to decreased use of prenatal care for immigrant mothers and declines in birth weight, according to new Duke University research.

In the study, published in PLOS ONE, researchers examine the effects of the federal 287(g) immigration program after it was introduced in North Carolina in 2006. Under 287(g) programs, which are still in effect, local law officers are deputized to act as Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agents, with authority to question individuals about immigration status, detain them, and if necessary, begin deportation proceedings.

According to the study findings, the 2006 policy change reduced birth weight ...

BIRMINGHAM, Ala. - Hypoxia -- where a tissue is deprived of an adequate supply of oxygen -- is a feature inside solid cancer tumors that renders them highly invasive and resistant to treatment. Study of how cells adapt to this critical stressor, by altering their metabolism to survive in a low-oxygen environment, is important to better understand tumor growth and spread.

Researchers led by Rajeev Samant, Ph.D., professor of pathology at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, now report that chronic hypoxia, surprisingly, upregulates RNA polymerase I activity and alters the methylation patterns on ribosomal RNAs. These altered epigenetic marks on the ribosomal RNAs appear to create a pool of specialized ribosomes that can differentially ...

As a native animal, kangaroos aren't typically considered a threat to Australian vegetation.

While seen as a pest on farmland - for example, when competing with livestock for resources - they usually aren't widely seen as a pest in conservation areas.

But a new collaborative study led by UNSW Sydney found that conservation reserves are showing signs of kangaroo overgrazing - that is, intensive grazing that negatively impacts the health and biodiversity of the land.

Surprisingly, the kangaroos' grazing impacts appeared to be more damaging to the land than rabbits, an introduced species.

"The kangaroos had severe impacts on soils and vegetation that were symptomatic of overgrazing," says Professor Michael Letnic, senior author of the paper and ...

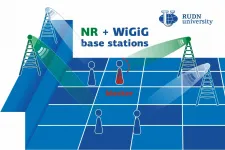

Mathematicians from RUDN University suggested and tested a new method to assess the productivity of fifth-generation (5G) base stations. The new technology would help get rid of mobile access stations and even out traffic fluctuations. The results of the study were published in the IEEE Conference Publication.

Stations of the new 5G New Radio (NR) communication standard developed by the 3GPP consortium are expected to shortly be installed in large quantities all over the world. First of all, the stations will be deployed in places with high traffic ...

ITHACA, N.Y. -Wind energy scientists at Cornell University have released a new global wind atlas - a digital compendium filled with documented extreme wind speeds for all parts of the world - to help engineers select the turbines in any given region and accelerate the development of sustainable energy.

This wind atlas is the first publicly available, uniform and geospatially explicit (datasets tied to locations) description of extreme wind speeds, according to the research, "A Global Assessment of Extreme Wind Speeds For Wind Energy Applications," published in Nature Energy.

"Cost-efficient expansion of the wind-energy industry is enabled by access ...

One of the most important ways to stop the spread of COVID-19 is for people who have tested positive, or have symptoms, to isolate themselves from the other people they live with.

But a new University of Michigan poll suggests that nearly one in five older adults don't have the ability to do this - and that those who are Hispanic or Black, or who have lower incomes or poor health to begin with, are more likely to lack a safe isolation place in their home.

The poll also shows significant inequality in another key aspect of staying safe and healthy during the pandemic: the ability to get outside for fresh air and exercise, and to engage safely with friends, ...

Despite worldwide use of lithium batteries, the exact dynamics of their operation has remained elusive. X-rays have proven to be a powerful tool for peering inside of these batteries to see the changes that occur in real time.

Using the ultrabright X-rays of the Advanced Photon Source (APS), a U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science User Facility at the DOE's Argonne National Laboratory, a research team recently observed the internal evolution of the materials inside solid-state lithium batteries as they were charged and discharged. This detailed 3D ...

The speed of light has come to 3D printing. Northwestern University engineers have developed a new method that uses light to improve 3D printing speed and precision while also, in combination with a high-precision robot arm, providing the freedom to move, rotate or dilate each layer as the structure is being built.

Most conventional 3D printing processes rely on replicating a digital design model that is sliced into layers with the layers printed and assembled upwards like a cake. The Northwestern method introduces the ability to manipulate the original design layer by layer and pivot the printing direction without recreating the model. This "on-the-fly" ...

How do the normal pains of everyday life, such as headaches and backaches, influence our ability to think? Recent studies suggest that healthy individuals in pain also show deficits in working memory, or the cognitive process of holding and manipulating information over short periods of time. Prior research suggests that pain-related impairments in working memory depend on an individual's level of emotional distress. Yet the specific brain and psychological factors underlying the role of emotional distress in contributing to this relationship are not well understood.

A new study, titled "Modeling neural and self-reported factors of affective distress in the relationship between pain and working memory in healthy individuals," and published in the journal ...