(Press-News.org) The distinctive gut microbiome profile of a person with liver cancer linked to non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) could be the key to predicting someone's risk of developing the cancer, say researchers from the UNSW Microbiome Research Centre (MRC).

Their new study, published in Nature Communications recently, found the gut microbiome - the kingdom of microorganisms living in our digestive tracts - can modulate the immune response in liver cancer patients with NAFLD, in a way that promotes the cancer's survival.

While the research is still in its early stages, this finding could lead to more effective preventative and therapeutic treatments for people at risk of developing NAFLD-related liver cancer.

People develop NAFLD in the context of obesity and metabolic risk factors such as diabetes, hypertension and high cholesterol.

Senior author Associate Professor Amany Zekry, of UNSW Medicine & Health, said the researchers looked at the most common type of primary liver cancer - hepatocellular carcinoma or HCC - which is the third leading cause of cancer-related deaths worldwide.

"Chronic liver inflammation and liver cirrhosis - or scarring - are key to a patient developing liver cancer, with NAFLD a common risk factor," A/Prof. Zekry said.

"So, because of the global pandemic of obesity and type 2 diabetes, NAFLD is emerging as the key reason for liver disease and liver cancer - particularly in western countries.

"Liver cancer generally has a bad outcome because it's usually detected at the late stages of the disease due to the liver's resilience - liver cirrhosis can go undiagnosed for many years until cancer develops."

In Australia, people have a 20 per cent chance of surviving for at least five years after being diagnosed with liver cancer.

The UNSW-led study included medical researchers from UNSW's St George and Sutherland Clinical School and major hospitals in NSW.

A/Prof. Zekry, who is also the Head of Gastroenterology and Hepatology at St George Hospital, said their research was the first paper to comprehensively investigate the microbiome in the context of NAFLD-related liver cancer.

"Another unique feature of our research is how we used a human cell culture model to examine the effect of the gut microbiome on the immune response in liver cancer patients," she said.

"This study is part of a larger research project we are doing involving about 200 patients - with the ultimate aim of identifying gut microbiome biomarkers or indicators, to predict someone's risk of developing liver cancer.

"The gut microbiome plays an important role in diseases generally and a person's overall health - so, our lifestyle and the food and drink we consume can influence this kingdom of microorganisms living in all of us."

Early stage cancer patients studied

The researchers recruited 90 adult patients from several Sydney hospitals, two-thirds of whom had just been diagnosed with either NAFLD-related liver cancer or cirrhosis.

The remaining third of patients was a control group without liver disease.

The patients with liver cancer, aged in their 50s to 70s, were selected because their cancer had been detected early.

A/Prof. Zekry said this was the best cohort to examine because researchers wanted to understand what occurred in the early stage of the disease.

All patients provided blood and stool samples, which the researchers used to create cell culture models for analysis.

A/Prof. Zekry said: "If we know what happens in the early stage, then we can intervene to stop the cancer progressing to the late stage.

"So, if people can be diagnosed early with liver cancer, there is the potential to cure them with definitive therapy.

"Our study findings also open the door to harness gut-based interventions, by manipulating the microbiome, as a preventative strategy against the development of liver cancer."

Discovery of a liver cancer 'signature'

The researchers found patients with NAFLD-related liver cancer had a distinctive and characteristic gut microbiome profile, which was different to those with liver disease generally.

The study's first author Dr Jason Behary, Conjoint Associate Lecturer at UNSW Medicine & Health, said it was an exciting discovery because no past studies had reported a NAFLD-related liver cancer "signature".

"This means in the future, we will be able to harness the gut microbiome to predict disease occurrence, which is highly relevant for liver cancer because it's almost always detected in the late stages," he said.

"We also found the genes and function of the gut microbiome in NAFLD-related liver cancer patients promoted increased production of short-chain fatty acids - namely butyrate - which stem from intestinal microbial fermentation of indigestible foods, like beans and grains.

"Excess butyrate in the context of liver cancer is hazardous, because we found it obstructs the immune system from functioning.

"In addition, we found certain bacteria species correlated with this unfavourable immune response."

Dr Behary, a gastroenterologist and hepatologist and PhD candidate, said the cell culture studies confirmed the gut microbiome of patients with NAFLD-related liver cancer modulated the immune response in a way that favoured the cancer's survival - rather than its elimination.

"So, because we have shown the gut microbiome can influence the immune response at an early stage to tolerate the liver cancer, this opens the door for intervention," he said.

"And, given the growing interest in new liver cancer treatments like immunotherapy - drugs which change the immune response to make it fight the cancer, rather than welcome it - our findings will pave the way for future studies to look at how we can change the microbiome to increase the chances of immunotherapy being successful."

A vision for predicting cancer risk

A/Prof. Zekry acknowledged the researchers were several years away from their work having a direct impact for people at risk of developing NAFLD-related liver cancer.

"What we have is a proof of concept - so, now we need to define a pilot study to prove that concept and provide more definitive answers," she said.

"For example, we need to find a control group with diabetes but not liver disease, in order to examine the effect of diabetes on the gut microbiome without the presence of NAFLD.

"But it is difficult to recruit such a group in clinical practice because liver disease is present in almost 80 per cent of patients with diabetes."

Despite these challenges, A/Prof. Zekry said the team had new research in train at the MRC under the leadership of study co-author Professor Emad El-Omar, the Professor of Medicine at St George and Sutherland Clinical School.

Their new work includes animal studies to understand the mechanisms of how the gut microbiome influences immune response.

A/Prof. Zekry said: "We have exciting projects ongoing - we are trying to understand how the microbiome influences the immune response to cause liver cancer, as well as finding out how to switch off a 'bad' microbiome and switch on the 'good' ones to prevent liver cancer.

"We are also investigating microbiome-based biomarkers to predict liver cancer risk.

"It is our vision for people to be able to get a test, via a mouth swab, blood or stool sample, to determine if they carry a 'signature' which shows they are at risk of developing liver cancer."

INFORMATION:

Find the study in Nature Communications: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-20422-7

The intestine harbors the largest number of immune cells in our body. Since the intestine is constantly exposed to various antigens like bacteria and food, appropriate induction of gut immune cells plays a pivotal role in gut homeostasis.

A POSTECH research team - led by Professor Seung-Woo Lee, Ph.D. candidate Sookjin Moon and research assistant professor Yunji Park of the Department of Life Sciences - has uncovered for the first the mechanism for regulating the differentiation of T cells (intraepithelial lymphocyte, IEL) via intestinal epithelial cells (IEC). These findings were recently published in the Journal of Experimental Medicine ...

Cells replicate their genetic material and divide into two identical clones, perpetuating life -- until they don't. Some cells pause -- or are intentionally made to pause -- in the process. When the cell resumes division after such a pause, a displaced nucleus -- an essential part of cell survival -- can become caught in the fissure, splitting violently and killing both cells. But that is not always the case; some mutant cells can recover by pushing their nucleus to safety. Researchers from Hiroshima University in Japan are starting to understand how in the first step toward potential cell death rescue applications.

The results were published on Jan. 22 in iScience, a Cell Press journal.

The researchers examined fission yeast, a common model organism ...

This is the finding of an 18-year-study of over 300,000 people with diabetes in England, from scientists from Imperial College London and published in the journal The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology.

Thursday Feb 4th is World Cancer Day.

The research, funded by the Wellcome Trust, reveals that between 2001-2018 heart disease and stroke were no longer the leading causes of death among people with diabetes, as they were 18 years ago.

Diabetes affects 4.7 million people in the UK, and is caused by the body being unable to regulate blood sugar levels. Around 90 per cent have type ...

Osaka - Many different catalysts that promote the conversion of glucose to sorbitol have been studied; however, most offer certain properties while requiring compromises on others. Now, researchers from Osaka University have reported a hydrotalcite-supported nickel phosphide nanoparticle catalyst (nano-Ni2P/HT) that ticks all the boxes. Their findings are published in Green Chemistry.

Sorbitol is a versatile molecule that is widely used in the food, cosmetics, and pharmaceuticals industries. There is therefore a pressing need to produce sorbitol in a sustainable, low-cost, and green manner.

The nickel catalysts that are commonly used in the industrial hydrogenation of glucose to sorbitol are unstable in air and require hash reaction conditions. Rare metal alternatives--despite being ...

Remember the first rule of fight club? That's right: You don't talk about fight club. Luckily, the rules of Hollywood don't apply to science. In new published research, University of Arizona researchers report what they learned when they started their own "fight club" - an exclusive version where only insects qualify as members, with a mission to shed light on the evolution of weapons in the animal kingdom.

In many animal species, fighting is a common occurrence. Individuals may fight over food, shelter or territory, but especially common are fights between males over access to females for mating. Many of the most striking and unusual features of animals are associated with these mating-related fights, including the horns of beetles and the antlers of deer. What is less clear ...

PHILADELPHA--Inflammation in the blood could serve as a new biomarker to help identify patients with advanced pancreatic cancer who won't respond to the immune-stimulating drugs known as CD40 agonists, suggests a new study from researchers in the Abramson Cancer Center of the University of Pennsylvania published in JCI Insight

It is known that pancreatic cancer can cause systemic inflammation, which is readily detectable in the blood. The team found that patients with systemic inflammation had worse overall survival rates than patients without inflammation when treated with both a CD40 agonist and the chemotherapy gemcitabine.

The ...

This study is the first randomised control trial to rigorously test a sequential approach to treating comorbid PTSD and major depressive disorder.

Findings from a trial of 52 patients undergoing three types of treatment regime - using only Cognitive Processing Therapy (CPT), using Behavioural Activation Therapy (BA) with some CPT, or CPT with some BA - found that a combined treatment protocol resulted in meaningful reductions in PTSD and depression severity, with improvements maintained at six-month follow-up investigations.

"We sought to examine whether a protocol that specifically targeted both PTSD and comorbid ...

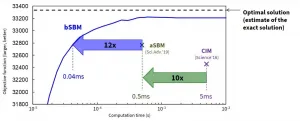

TOKYO --Toshiba Corporation (TOKYO: 6502) and Toshiba Digital Solutions Corporation (collectively Toshiba), industry leaders in solutions for large-scale optimization problems, today announced the Ballistic Simulated Bifurcation Algorithm (bSB) and the Discrete Simulated Bifurcation Algorithm (dSB), new algorithms that far surpass the performance of Toshiba's previous Simulated Bifurcation Algorithm (SB). The new algorithms will be applied to finding solutions to highly complex problems in areas as diverse as portfolio management, drug development and logistics management. ...

Borderline Personality Disorder, or BPD, is the most common personality disorder in Australia, affecting up to 5% of the population at some stage, and Flinders University researchers warn more needs to be done to meet this high consumer needs.

A new study in the Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing (Wiley) describes how people with BPD are becoming more knowledgeable about the disorder and available treatments, but may find it difficult to find evidence-based help for their symptoms.

The South Australian psychiatric researchers warn these services are constrained by stigma ...

Researchers at Flinders University are working to remedy this situation by identifying what triggers this chronic pain in the female reproductive tract.

Dr Joel Castro Kraftchenko - Head of Endometriosis Research for the Visceral Pain Group (VIPER), with the College of Medicine and Public Health at Flinders University - is leading research into the pain attached to Dyspareunia, also known as vaginal hyperalgesia or painful intercourse, which is one of the most debilitating symptoms experienced by women with endometriosis and vulvodynia.

Pain is detected by specialised proteins (called ion channels) that are present in sensory nerves and project from peripheral organs to the central ...