(Press-News.org) CAMBRIDGE, MA -- Cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) allows scientists to produce high-resolution, three-dimensional images of tiny molecules such as proteins. This technique works best for imaging proteins that exist in only one conformation, but MIT researchers have now developed a machine-learning algorithm that helps them identify multiple possible structures that a protein can take.

Unlike AI techniques that aim to predict protein structure from sequence data alone, protein structure can also be experimentally determined using cryo-EM, which produces hundreds of thousands, or even millions, of two-dimensional images of protein samples frozen in a thin layer of ice. Computer algorithms then piece together these images, taken from different angles, into a three-dimensional representation of the protein in a process termed reconstruction.

In a Nature Methods paper, the MIT researchers report a new AI-based software for reconstructing multiple structures and motions of the imaged protein -- a major goal in the protein science community. Instead of using the traditional representation of protein structure as electron-scattering intensities on a 3D lattice, which is impractical for modeling multiple structures, the researchers introduced a new neural network architecture that can efficiently generate the full ensemble of structures in a single model.

"With the broad representation power of neural networks, we can extract structural information from noisy images and visualize detailed movements of macromolecular machines," says Ellen Zhong, an MIT graduate student and the lead author of the paper.

With their software, they discovered protein motions from imaging datasets where only a single static 3D structure was originally identified. They also visualized large-scale flexible motions of the spliceosome -- a protein complex that coordinates the splicing of the protein coding sequences of transcribed RNA.

"Our idea was to try to use machine-learning techniques to better capture the underlying structural heterogeneity, and to allow us to inspect the variety of structural states that are present in a sample," says Joseph Davis, the Whitehead Career Development Assistant Professor in MIT's Department of Biology.

Davis and Bonnie Berger, the Simons Professor of Mathematics at MIT and head of the Computation and Biology group at the Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory, are the senior authors of the study, which appears today in Nature Methods. MIT postdoc Tristan Bepler is also an author of the paper.

Visualizing a multistep process

The researchers demonstrated the utility of their new approach by analyzing structures that form during the process of assembling ribosomes -- the cell organelles responsible for reading messenger RNA and translating it into proteins. Davis began studying the structure of ribosomes while a postdoc at the Scripps Research Institute. Ribosomes have two major subunits, each of which contains many individual proteins that are assembled in a multistep process.

To study the steps of ribosome assembly in detail, Davis stalled the process at different points and then took electron microscope images of the resulting structures. At some points, blocking assembly resulted in accumulation of just a single structure, suggesting that there is only one way for that step to occur. However, blocking other points resulted in many different structures, suggesting that the assembly could occur in a variety of ways.

Because some of these experiments generated so many different protein structures, traditional cryo-EM reconstruction tools did not work well to determine what those structures were.

"In general, it's an extremely challenging problem to try to figure out how many states you have when you have a mixture of particles," Davis says.

After starting his lab at MIT in 2017, he teamed up with Berger to use machine learning to develop a model that can use the two-dimensional images produced by cryo-EM to generate all of the three-dimensional structures found in the original sample.

In the new Nature Methods study, the researchers demonstrated the power of the technique by using it to identify a new ribosomal state that hadn't been seen before. Previous studies had suggested that as a ribosome is assembled, large structural elements, which are akin to the foundation for a building, form first. Only after this foundation is formed are the "active sites" of the ribosome, which read messenger RNA and synthesize proteins, added to the structure.

In the new study, however, the researchers found that in a very small subset of ribosomes, about 1 percent, a structure that is normally added at the end actually appears before assembly of the foundation. To account for that, Davis hypothesizes that it might be too energetically expensive for cells to ensure that every single ribosome is assembled in the correct order.

"The cells are likely evolved to find a balance between what they can tolerate, which is maybe a small percentage of these types of potentially deleterious structures, and what it would cost to completely remove them from the assembly pathway," he says.

Viral proteins

The researchers are now using this technique to study the coronavirus spike protein, which is the viral protein that binds to receptors on human cells and allows them to enter cells. The receptor binding domain (RBD) of the spike protein has three subunits, each of which can point either up or down.

"For me, watching the pandemic unfold over the past year has emphasized how important front-line antiviral drugs will be in battling similar viruses, which are likely to emerge in the future. As we start to think about how one might develop small molecule compounds to force all of the RBDs into the 'down' state so that they can't interact with human cells, understanding exactly what the 'up' state looks like and how much conformational flexibility there is will be informative for drug design. We hope our new technique can reveal these sorts of structural details," Davis says.

INFORMATION:

The research was funded by the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship Program, the National Institutes of Health, and the MIT Jameel Clinic for Machine Learning and Health. This work was supported by MIT Satori computation cluster hosted at the MGHPCC.

The next time you tuck in to a tikka masala you might find yourself asking a burning question: are spices used in dishes to help stop infection?

It's a question many have chewed the fat over. And now thanks to new research from The Australian National University (ANU) we have an answer.

The quick takeaway is: probably not.

Professor Lindell Bromham and her colleagues asked why hot countries across the world tend to have spicy food? This pattern has led to what some have termed "Darwinian gastronomy" - a tummy-led cultural evolutionary process in countries with hotter climates.

To find out the answer to their question, the researchers feasted on a true ...

You might remember you ate cereal for breakfast but forget the color of the bowl. Or recall watching your partner put the milk away but can't remember on which shelf.

A new Northwestern Medicine study improved memory of complex, realistic events similar to these by applying transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) to the brain network responsible for memory. The authors then had participants watch videos of realistic activities to measure how memory works during everyday tasks. The findings prove it is possible to measure and manipulate realistic types of memory.

"On a day-to-day basis we must remember complex events that involve many elements, such as different locations, people and objects," said lead author Melissa Hebscher, a postdoctoral fellow ...

New tools and methods have been described by WEHI researchers to study an unusual protein modification and gain fresh insights into its roles in human health and disease.

The study - about how certain sugars modify proteins - was published today in Nature Chemical Biology. Led by WEHI researcher Associate Professor Ethan Goddard-Borger, this work lays a foundation for better understanding diseases like muscular dystrophy and cancer.

At a glance

WEHI researchers have developed new tools and methods to determine how 'tryptophan C-mannosylation', an unusual protein modification, impacts the stability and function ...

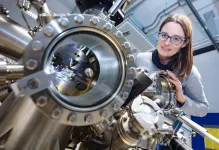

In order to produce tiny electronic memories or sensors in future, it is essential to be able to arrange individual metal atoms on an insulating layer. Scientists at Bielefeld University's Faculty of Chemistry have now demonstrated that this is possible at room temperature: molecules of the metal-containing compound molybdenum acetate form an ordered structure on the insulator calcite without jumping to other positions or rotating. Their findings have been presented in the Nature Communications journal. The work was done in cooperation with researchers from the universities of Kaiserslautern, Lincoln (UK) and Mainz.

'Until now, it has been difficult ...

A healthy person has a general balance of good and bad bacteria. But that balance is thrown off when someone gets sick. So, to help boost their levels of good bacteria, many people take probiotic supplements -- live bacteria inside of a pill. Various commercial probiotic supplements are available for consumer purchase, and while health experts generally agree about their overall safety, controversy surrounds their efficacy.

Inside the human body lives a large microscopic community called the microbiome, where trillions of bacteria engage in a constant "tug of war" to maintain optimal levels of good and bad bacteria. Most of this struggle takes place within the body's gastrointestinal tract, as bacteria help with digesting food and support the immune system. Although ...

New research carried out by City data scientist, Dr Andrea Baronchelli, and colleagues, into the dark web marketplace (DWM) trade in products related to COVID-19, has revealed the need for the continuous monitoring of dark web marketplaces (DWMs), especially in light of the current shortage and availability of coronavirus vaccines.

In their paper, Dark Web Marketplaces and COVID-19: before the vaccine published in the EPJ Data Science journal, Dr Baronchelli and his colleagues analysed 851,199 listings extracted from 30 DWMs between January 1, 2020 and November 16, 2020 before the advent of the availability of the coronavirus vaccine.

They identify 788 listings directly related to COVID-19 products and monitor the temporal evolution of product categories including Personal Protective ...

Researchers from the University of Missouri School of Medicine have discovered that children who receive a seasonal flu shot are less likely to suffer symptoms from a COVID-19 infection. The finding comes from a review of more than 900 children diagnosed with COVID-19 in 2020.

"It is known that the growth of one virus can be inhibited by a previous viral infection," said Anjali Patwardhan, MD, professor of pediatric rheumatology and child health. "This phenomenon is called virus interference, and it can occur even when the first virus invader is an inactivated virus, such as the case with the flu vaccine."

Patwardhan reviewed records from 905 pediatric patients diagnosed with COVID-19 between February and August 2020 to determine each patient's influenza vaccination history. ...

Cardiac patients who also have diabetes will be able to do their rehabilitation exercises more safely, thanks to the world's first guidance on the subject, which has been published by international experts including a Swansea University academic.

The guidance will be a crucial resource for healthcare professionals, so they can help the growing number of cardiac rehabilitation patients who also have diabetes.

The guidance, approved by international diabetes organisations, was drawn up by a team including Dr. Richard Bracken of the School of ...

Scientists at Bielefeld University's Faculty of Physics have succeeded for the first time in imaging the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus with a helium ion microscope. In contrast to the more conventional electron microscopy, the samples do not need a thin metal coating in helium ion microscopy. This allows interactions between the coronaviruses and their host cell to be observed particularly clearly. The scientists have published their findings, obtained in collaboration with researchers from Bielefeld University's Medical School OWL and Justus Liebig University Giessen, in the Beilstein Journal of Nanotechnology.

'The study shows that the helium ion microscope is suitable for imaging coronaviruses - so precisely that the interaction between virus ...

People undergoing long-term dialysis are almost 4 times more likely to die from COVID-19 and should be prioritized for vaccination, found a new Ontario study published in CMAJ (Canadian Medical Association Journal).

"As the COVID-19 pandemic proceeds, focused efforts should be made to protect this population from infection including prioritizing patients on long-term dialysis and the staff treating them for SARS-CoV-2 vaccination," writes Dr. Peter Blake, provincial director, Ontario Renal Network, Ontario Health, and professor, Schulich School of Medicine and Dentistry, Western University, ...