(Press-News.org) Although scientists knew that some bats could reach heights of over 1,600 meters (or approximately one mile) above the ground during flight, they didn't understand how they managed to do it without the benefit of thermals that aren't typically available to them during their nighttime forays. Now, researchers reporting in the journal Current Biology on February 4th have uncovered the bats' secret to high-flying.

It turns out that the European free-tailed bats they studied--powerful fliers that the researchers documented sometimes reaching speeds of up to 135 kilometers (84 miles) per hour in self-powered flight--do depend on orographic uplift that happens when air is pushed up over rising terrain to help them fly high, just as birds do during the day. But, because that's harder to find during the cooler night, they have to rely on just the right sort of areas to reach those high altitudes.

"We show that wind and topography can predict areas of the landscape able to support high-altitude ascents, and that bats use these locations to reach high altitudes while reducing airspeeds," explains Teague O'Mara (@teague_o), of Southeastern Louisiana University and the Max Planck Institute of Animal Behavior. "Bats then integrate wind conditions to guide high-altitude ascents, deftly exploiting vertical wind energy in the nocturnal landscape."

To make these discoveries, O'Mara and colleagues fitted the free-tailed bats with high-resolution GPS loggers that recorded their location in three-dimensional space every 30 seconds, tracking them for up to three days during the approximately six-hour night. The data show that bats emerge just after sunset and fly constantly throughout the night before returning to roost.

They observed that the bats' flight would typically follow the terrain they crossed, but that occasionally they would climb to extreme heights, reaching nearly a mile above ground level in less than 20 minutes. During these high-altitude ascents, the bats would climb faster, longer, and at a lower airspeed than during more moderate ascents to around 300 meters. Most bats descended quickly after reaching their peak elevation, resulting in a kind of rollercoaster flight path.

The researchers were surprised to discover just how predictable the bats' high-flying ascents were across the landscape. The data show that bats are using the same types of places--although not necessarily always the exact same locations--where the wind sweeps up a slope to carry them to high altitudes.

"We were ready to see that these bats flew fast, so that wasn't a surprise to us," O'Mara said. "But the fast, uplifting wind-supported flights were something our team really wasn't looking for or prepared for."

The findings show that bats are solving the problems of flight in similar ways to birds--just at night, the researchers note.

"These free-tailed bats seem to find ways to minimize how much energy they have to spend to find food each night," O'Mara said. "It's a pretty incredible challenge for an animal that can only really perceive the 30 to 50 meters ahead of it in detail. It takes a lot of energy to fly up to 1,600 meters above the ground, and these bats have found a way to ride the wind currents up."

Although the researchers already had a pretty good idea based on past work that the bats also could fly amazingly fast, they say this fast-flying ability remains "a bit of an unsolved problem."

"Their small body sizes and large, flexible wings covered in a thin membrane were assumed to prevent these really fast speeds," O'Mara said. "But it's now clear that bats can fly incredibly fast when they choose. It's up to us to figure out how they do that and if it can be applied to other scenarios," such as engineering bio-inspired high-speed and low-energy flight.

INFORMATION:

This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft under Germany's Excellence Strategy, the Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, Portugal, and the Energias de Portugal Biodiversity Chair.

Current Biology, O'Mara et al.: "Bats use topography and nocturnal updrafts to fly high and fast" https://www.cell.com/current-biology/fulltext/S0960-9822(20)31894-7

Current Biology (@CurrentBiology), published by Cell Press, is a bimonthly journal that features papers across all areas of biology. Current Biology strives to foster communication across fields of biology, both by publishing important findings of general interest and through highly accessible front matter for non-specialists. Visit: http://www.cell.com/current-biology. To receive Cell Press media alerts, contact press@cell.com.

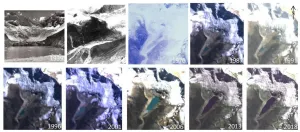

As the planet warms, glaciers are retreating and causing changes in the world's mountain water systems. For the first time, scientists at the University of Oxford and the University of Washington have directly linked human-induced climate change to the risk of flooding from a glacial lake known as one of the world's greatest flood risks.

The study examined the case of Lake Palcacocha in the Peruvian Andes, which could cause flooding with devastating consequences for 120,000 residents in the city of Huaraz. The paper, published Feb. 4 in Nature Geoscience, provides new evidence for an ongoing legal case that hinges on the link between greenhouse gas emissions and particular climate change impacts.

"The scientific challenge was to provide the clearest and cleanest assessment ...

CHICAGO - A new study by Northwestern University researchers finds involvement with firearms by high-risk youth is associated with firearm violence during adulthood.

"Association of Firearm Access, Use, and Victimization During Adolescence with Firearm Perpetration During Adulthood in a 16-year Longitudinal Study of Youth Involved in the Juvenile Justice System" will publish in JAMA Network Open at 10 a.m. CST, Thursday, Feb. 4. Access the full study online.

The longitudinal study of juvenile justice youth is the first to analyze firearm victimization and access during adolescence and its association with firearm violence in adulthood.

The study is based ...

Toronto - (February 4, 2021) The results of a Phase III randomized clinical trial have shown that when it comes to detecting clinically significant prostate cancer, Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) with targeted biopsies (MRI-TBx) matches the current standard and brings a multitude of advantages. The PRostate Evaluation for Clinically Important Disease: MRI vs Standard Evaluation Procedures (PRECISE) study will help to make prostate cancer diagnosis more accurate and less invasive.

PRECISE included 453 participants at Canadian academic cancer centres who were either assigned to receive MRI ...

What The Study Did: Researchers estimated the rate of nurse burnout in the United States and the factors associated with leaving or considering leaving their jobs due to burnout.

Authors: Megha K. Shah, M.D., M.Sc., of the Emory University School of Medicine in Atlanta, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.36469)

Editor's Note: The article includes conflict of interest and funding/support disclosures. Please see the article for additional information, ...

What The Study Did: Researchers in this randomized clinical trial investigated whether nasopharyngeal application of povidone iodine could reduce the viral load of patients with nonsevere COVID-19 symptoms.

Authors: Olivier Mimoz, M.D., Ph.D., University Hospital of Poitiers in Poitiers, France, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamaoto.2020.5490)

Editor's Note: The article includes conflict of interest and funding/support disclosures. Please see the article for additional information, including other authors, author contributions and affiliations, conflict of interest and financial disclosures, ...

What The Study Did: This randomized clinical trial looked at changes in levels of the hormone estradiol in men with hormone receptor-positive breast cancer after three months of treatment with endocrine therapies.

Authors: Sibylle Loibl, M.D., Ph.D., of the German Breast Group in Neu-Isenburg, Germany, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.7442)

Editor's Note: The article includes conflicts of interest and funding/support disclosures. Please see the article ...

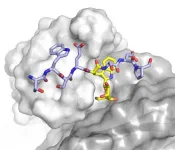

CAMBRIDGE, MA -- Cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) allows scientists to produce high-resolution, three-dimensional images of tiny molecules such as proteins. This technique works best for imaging proteins that exist in only one conformation, but MIT researchers have now developed a machine-learning algorithm that helps them identify multiple possible structures that a protein can take.

Unlike AI techniques that aim to predict protein structure from sequence data alone, protein structure can also be experimentally determined using cryo-EM, which produces hundreds of thousands, or even millions, of two-dimensional images of protein samples frozen in a thin layer of ice. Computer algorithms then piece together these images, taken from different angles, into a three-dimensional ...

The next time you tuck in to a tikka masala you might find yourself asking a burning question: are spices used in dishes to help stop infection?

It's a question many have chewed the fat over. And now thanks to new research from The Australian National University (ANU) we have an answer.

The quick takeaway is: probably not.

Professor Lindell Bromham and her colleagues asked why hot countries across the world tend to have spicy food? This pattern has led to what some have termed "Darwinian gastronomy" - a tummy-led cultural evolutionary process in countries with hotter climates.

To find out the answer to their question, the researchers feasted on a true ...

You might remember you ate cereal for breakfast but forget the color of the bowl. Or recall watching your partner put the milk away but can't remember on which shelf.

A new Northwestern Medicine study improved memory of complex, realistic events similar to these by applying transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) to the brain network responsible for memory. The authors then had participants watch videos of realistic activities to measure how memory works during everyday tasks. The findings prove it is possible to measure and manipulate realistic types of memory.

"On a day-to-day basis we must remember complex events that involve many elements, such as different locations, people and objects," said lead author Melissa Hebscher, a postdoctoral fellow ...

New tools and methods have been described by WEHI researchers to study an unusual protein modification and gain fresh insights into its roles in human health and disease.

The study - about how certain sugars modify proteins - was published today in Nature Chemical Biology. Led by WEHI researcher Associate Professor Ethan Goddard-Borger, this work lays a foundation for better understanding diseases like muscular dystrophy and cancer.

At a glance

WEHI researchers have developed new tools and methods to determine how 'tryptophan C-mannosylation', an unusual protein modification, impacts the stability and function ...