(Press-News.org) For patients with cancers that do not respond to immunotherapy drugs, adjusting the composition of microorganisms in the intestines--known as the gut microbiome--through the use of stool, or fecal, transplants may help some of these individuals respond to the immunotherapy drugs, a new study suggests. Researchers at the National Cancer Institute (NCI) Center for Cancer Research, part of the National Institutes of Health, conducted the study in collaboration with investigators from UPMC Hillman Cancer Center at the University of Pittsburgh.

In the study, some patients with advanced melanoma who initially did not respond to treatment with an immune checkpoint inhibitor, a type of immunotherapy, did respond to the drug after receiving a transplant of fecal microbiota from a patient who had responded to the drug. The results suggest that introducing certain fecal microorganisms into a patient's colon may help the patient respond to drugs that enhance the immune system's ability to recognize and kill tumor cells. The findings appeared in Science on February 4, 2021.

"In recent years, immunotherapy drugs called PD-1 and PD-L1 inhibitors have benefited many patients with certain types of cancer, but we need new strategies to help patients whose cancers do not respond," said study co-leader Giorgio Trinchieri, M.D., chief of the Laboratory of Integrative Cancer Immunology in NCI's Center for Cancer Research. "Our study is one of the first to demonstrate in patients that altering the composition of the gut microbiome can improve the response to immunotherapy. The data provide proof of concept that the gut microbiome can be a therapeutic target in cancer."

More research is needed, Dr. Trinchieri added, to identify the specific microorganisms that are critical for overcoming a tumor's resistance to immunotherapy drugs and to investigate the biological mechanisms involved.

Research suggests that communities of bacteria and viruses in the intestines can affect the immune system and its response to chemotherapy and immunotherapy. For example, previous studies have shown that tumor-bearing mice that do not respond to immunotherapy drugs can start to respond if they receive certain gut microorganisms from mice that responded to the drugs.

Changing the gut microbiome may "reprogram" the microenvironments of tumors that resist immunotherapy drugs, making them more favorable to treatment with these medicines, noted Dr. Trinchieri.

To test whether fecal transplants are safe and may help patients with cancer better respond to immunotherapy, Dr. Trinchieri and his colleagues developed a small, single-arm clinical trial for patients with advanced melanoma. The patients' tumors had not responded to one or more rounds of treatment with the immune checkpoint inhibitors pembrolizumab (Keytruda) or nivolumab (Opdivo), which were administered alone or in combination with other drugs. Immune checkpoint inhibitors release a brake that keeps the immune system from attacking tumor cells.

In the study, the fecal transplants, which were obtained from patients with advanced melanoma who had responded to pembrolizumab, were analyzed to ensure that no infectious agents would be transmitted. After treatment with saline and other solutions, the fecal transplants were delivered to the colons of patients through colonoscopies, and each patient also received pembrolizumab.

After these treatments, 6 out of 15 patients who had not originally responded to pembrolizumab or nivolumab responded with either tumor reduction or long-term disease stabilization. One of these patients has exhibited an ongoing partial response after more than two years and is still being followed by researchers, while four other patients are still receiving treatment and have shown no disease progression for over a year.

The treatment was well tolerated, though some of the patients experienced minor side effects that were associated with pembrolizumab, including fatigue.

The investigators analyzed the gut microbiota of all of the patients. The six patients whose cancers had stabilized or improved showed increased numbers of bacteria that have been associated with the activation of immune cells called T cells and with responses to immune checkpoint inhibitors.

In addition, by analyzing data on proteins and metabolites in the body, the researchers observed biological changes in patients who responded to the transplant. For example, levels of immune system molecules that are associated with resistance to immunotherapy declined, and levels of biomarkers that are associated with response increased.

Based on the study findings, the researchers suggest that larger clinical trials should be conducted to confirm the results and identify biological markers that could eventually be used to select patients who are most likely to benefit from treatments that alter the gut microbiome.

"We expect that future studies will identify which groups of bacteria in the gut are capable of converting patients who do not respond to immunotherapy drugs into patients who do respond," said Amiran Dzutsev, M.D., Ph.D., of NCI's Center for Cancer Research, co-first author of the study. "These could come from patients who have responded or from healthy donors. If researchers can identify which microorganisms are critical for the response to immunotherapy, then it may be possible to deliver these organisms directly to patients who need them, without requiring a fecal transplant," he added.

INFORMATION:

The clinical trial was conducted in collaboration with Merck, the maker of pembrolizumab.

About the NCI Center for Cancer Research (CCR): CCR comprises nearly 250 teams conducting basic, translational, and clinical research in the NCI intramural program--an environment supporting innovative science aimed at improving human health. CCR's clinical program is housed at the NIH Clinical Center--the world's largest hospital dedicated to clinical research. For more information about CCR and its programs, visit ccr.cancer.gov.

About the National Cancer Institute (NCI): NCI leads the National Cancer Program and NIH's efforts to dramatically reduce the prevalence of cancer and improve the lives of cancer patients and their families, through research into prevention and cancer biology, the development of new interventions, and the training and mentoring of new researchers. For more information about cancer, please visit the NCI website at cancer.gov or call NCI's contact center, the Cancer Information Service, at 1-800-4-CANCER (1-800-422-6237).

About the National Institutes of Health (NIH): NIH, the nation's medical research agency, includes 27 Institutes and Centers and is a component of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. NIH is the primary federal agency conducting and supporting basic, clinical, and translational medical research, and is investigating the causes, treatments, and cures for both common and rare diseases. For more information about NIH and its programs, visit nih.gov.

Competition among sperm cells is fierce - they all want to reach the egg cell first to fertilize it. A research team from Berlin now shows in mice that the ability of sperm to move progressively depends on the protein RAC1. Optimal amounts of active protein improve the competitiveness of individual sperm, whereas aberrant activity can cause male infertility.

It is literally a race for life when millions of sperm swim towards the egg cells to fertilize them. But does pure luck decide which sperm succeeds? As it turns out, there are differences in competitiveness between individual sperm. ...

Berkeley -- In the arid Mojave Desert, small burrowing mammals like the cactus mouse, the kangaroo rat and the white-tailed antelope squirrel are weathering the hotter, drier conditions triggered by climate change much better than their winged counterparts, finds a new study published today in Science.

Over the past century, climate change has continuously nudged the Mojave's searing summer temperatures ever higher, and the blazing heat has taken its toll on the desert's birds. Researchers have documented a collapse in the region's bird populations, likely resulting ...

Treatment for HIV has improved tremendously over the past 30 years; once a death sentence, the disease is now a manageable lifelong condition in many parts of the world. Life expectancy is about the same as that of individuals without HIV, though patients must adhere to a strict regimen of daily antiretroviral therapy, or the virus will come out of hiding and reactivate. Antiretroviral therapy prevents existing virus from replicating, but it can't eliminate the infection. Many ongoing clinical trials are investigating possible ways to clear HIV infection.

In a study published Feb. 4 in the journal Science, researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis have identified a potential way to eradicate ...

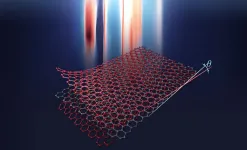

In 2018, the physics world was set ablaze with the discovery that when an ultrathin layer of carbon, called graphene, is stacked and twisted to a "magic angle," that new double layered structure converts into a superconductor, allowing electricity to flow without resistance or energy waste. Now, in a literal twist, Harvard scientists have expanded on that superconducting system by adding a third layer and rotating it, opening the door for continued advancements in graphene-based superconductivity.

The work is described in a new paper in Science and can one day help lead toward superconductors that operate at higher or even close to room temperature. These superconductors are considered the holy grail of condensed matter physics ...

Black children have significantly higher rates of shellfish and fish allergies than White children, in addition to having higher odds of wheat allergy, suggesting that race may play an important role in how children are affected by food allergies, researchers at Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children's Hospital of Chicago, Rush University Medical Center and two other hospitals have found.

Results of the study were published in the February issue of the Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology: In Practice.

"Food allergy is a common condition in the U.S., and we know from our previous research that there are important differences between Black and White children with food allergy, but there is so much we need to know to be able to help our patients ...

In a new perspective piece published in the Feb. 5 issue of Science, pharmacologist Namandje Bumpus, Ph.D. -- who recently became the first African American woman to head a Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine department, and is the only African American woman leading a pharmacology department in the country -- outlines the molecular origins for differences in how well certain drugs work among distinct populations. She also lays out a four-part plan to improve the equity of drug development.

"Human beings are more similar than we are different," says Bumpus. "Yet, the slightest variations in our genetic material ...

The COVID-19 pandemic has affected people's behavior everywhere. Fear, apprehensiveness, sadness, anxiety, and other troublesome feelings have become part of the daily lives of many families since the first cases of the disease were officially recorded early last year.

These turbulent feelings are often expressed in dreams reflecting a heavier burden of mental suffering, fear of contamination, stress caused by social distancing, and lack of physical contact with others. In addition, dream narratives in the period include a larger proportion of terms relating to cleanliness and contamination, as well as anger and sadness.

All this is reported in a study published in PLOS ONE. The principal investigator was Natália ...

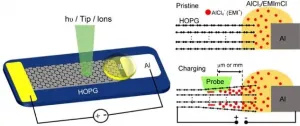

Surface and interface play critical roles in energy storage devices, thus calling for in-situ/operando methods to probe the electrified surface/interface. However, the commonly used in-situ/operando characterization techniques such as X-ray diffraction (XRD), transmission electron microscopy (TEM), X-ray spectroscopy and topography, and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) are based on the structural, electronic and chemical information in bulk region of the electrodes or electrolytes.

Surface science methodology including electron spectroscopy and scanning probe microscopy can provide rich information about how reactions ...

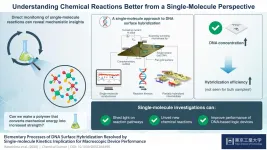

Scientists globally aim to control chemical reactions--an ambitious goal that requires identifying the steps taken by initial reactants to arrive at the final products as the reaction takes place. While this dream remains to be realized, techniques for probing chemical reactions have become sufficiently advanced to render it possible. In fact, chemical reactions can now be monitored based on the change of electronic properties of a single molecule! Thanks to the scanning tunneling microscope (STM), this is also simple to accomplish. Why not then utilize ...

Plastics are among the most successful materials of modern times. However, they also create a huge waste problem. Scientists from the University of Groningen (The Netherlands) and the East China University of Science and Technology (ECUST) in Shanghai produced different polymers from lipoic acid, a natural molecule. These polymers are easily depolymerized under mild conditions. Some 87 per cent of the monomers can be recovered in their pure form and re-used to make new polymers of virgin quality. The process is described in an article that was published in the journal Matter on 4 February.

A problem with recycling plastics is that it usually results in a lower-quality product. The best results are obtained by chemical recycling, in which the polymers are broken ...