(Press-News.org) For all their importance as a breakthrough treatment, the cancer immunotherapies known as checkpoint inhibitors still only benefit a small minority of patients, perhaps 15 percent across different types of cancer. Moreover, doctors cannot accurately predict which of their patients will respond.

A new study finds that inherited genetic variation plays a role in who is likely to benefit from checkpoint inhibitors, which release the immune system's brakes so it can attack cancer. The study also points to potential new targets that could help even more patients unleash their immune system's natural power to fight off malignant cells.

People who respond best to immunotherapy tend to have "inflamed" tumors that have been infiltrated by immune cells that are capable of killing both viruses and cancer. This inflammation is also driven by the immune signaling molecule interferon.

"There are some factors that are already associated with how well the immune system responds to tumors," said Elad Ziv, MD, professor of medicine at UCSF and co-senior author of the paper, published Feb. 9, 2021, by an international team in Immunity. "But what's been less studied is how well your genetic background predicts your immune system's response to the cancer. That's what is being filled in by this work: How much is the immune response to cancer affected by your inherited genetic variation?"

The study suggests that, for a range of important immune functions, as much as 20 percent of the variation in how different people's immune systems are able to attack cancer is due to the kind of genes they were born with, which are known as germline genetic variations.

That is a significant effect, similar to the size of the genetic contribution to traits like high blood sugar levels or obesity.

"Rather than testing selected genes, we analyzed all the genetic variants we could detect across the entire genome. Among all of them, the ones with the greatest effect on the immune system's response to the tumor were related to interferon signaling. Some of these variants are known to affect our response to viruses and our risk of autoimmune disorders," said Davide Bedognetti, MD, PhD, director of the Cancer Program at the Sidra Medicine Research Branch in Doha, Qatar, and co-senior author of the paper. "As observed with other diseases, we demonstrated that specific genes can also predispose someone to have a more effective anti-cancer immunity."

The team identified variants in 22 regions in the genome, or in individual genes, with significant effects - including one gene, IFIH1, that is already well known for the role its variants play in autoimmune diseases as varied as type 1 diabetes, psoriasis, vitiligo, systemic lupus erythematosus, ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease.

The IFIH1 variants act on cancer immunity in different ways. For instance, people with the variant that confers risk of type 1 diabetes had a more inflamed tumor, which suggests they would respond better to cancer immunotherapy. But the researchers saw the opposite effect for patients with the variant associated with Crohn's, indicating they might not benefit.

Another gene, STING1, was already thought to play a role in how patients respond to immunotherapy, and drug companies are looking for ways to boost its effects. But the team discovered that some people carry a variant that makes them less likely to respond, which may require further stratification of patients to know who could benefit most from those efforts.

The study required a huge amount of data that could only be found in a dataset as large as The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA), and from which they analyzed the genes and immune responses of 9,000 patients with 30 different kinds of cancer.

All told, the scientific team, which includes members from the United States, Qatar, Canada, and Europe, examined nearly 11 million gene variants to see how they matched with 139 immune parameters measured in patient tumor samples.

But the 22 regions or genes identified in the new study are just the tip of the iceberg, the researchers said, and they suspect many more germline genes likely play a role in how the immune system responds to cancer.

The next step, Ziv said, is to use the data to formulate "polygenic" approaches - taking a large number of genes into account to predict which cancer patients will benefit from current therapies, and developing new drugs for those who will not.

"It's further off," he said, "but it's a big part of what we hope will come out of this work."

INFORMATION:

The co-first authors are Rosalyn Sayaman, PhD, at UCSF and City of Hope and Mohamad Saad, PhD, of Qatar Computing Research Institute at Hamad Bin Khalifa University in Doha, Qatar.

See the paper online for additional author, funding and disclosure information.

About UCSF: The University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) is exclusively focused on the health sciences and is dedicated to promoting health worldwide through advanced biomedical research, graduate-level education in the life sciences and health professions, and excellence in patient care. UCSF Health, which serves as UCSF's primary academic medical center, includes top-ranked specialty hospitals and other clinical programs, and has affiliations throughout the Bay Area. Learn more at https://www.ucsf.edu, or see our Fact Sheet.

Follow UCSF

ucsf.edu | Facebook.com/ucsf | YouTube.com/ucsf

DALLAS, Feb. 10, 2021 — Reducing the prevalence of obesity may prevent up to half of new Type 2 diabetes cases in the United States, according to new research published today in the Journal of the American Heart Association, an open access journal of the American Heart Association. Obesity is a major contributor to diabetes, and the new study suggests more tailored efforts are needed to reduce the incidence of obesity-related diabetes.

Type 2 diabetes is the most common form of diabetes, affecting more than 31 million Americans, according to the U.S. Centers ...

Researchers at Uppsala University and the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences have used new methods for DNA sequencing and annotation to build a new, and more complete, dog reference genome. This tool will serve as the foundation for a new era of research, helping scientists to better understand the link between DNA and disease, in dogs and in their human friends. The research is presented in the journal Communications Biology.

The dog has been aiding our understanding of the human genome since both genomes were released in the early 2000s. At that time, a comparison of both genomes, and two others, revealed that the human genome contained circa 20,000 genes, down ...

Increased level of plasma cells linked to improved cancer survival

1,300 prostate tumor samples studied

Immunotherapy-based precision medicine clinical trials being developed

CHICAGO--- Black men die more often of prostate cancer yet, paradoxically, have greater survival benefits from immunotherapy treatment. A new Northwestern Medicine study discovered the reason appears to be an increase of a surprising type of immune cell in the tumor. The findings could lead to immune-based precision medicine treatment for men of all races with localized aggressive and advanced prostate cancer.

In the new study, Northwestern scientists showed tumors from Black men and men ...

CHAMPAIGN, Ill. -- When modified using a process known as epoxidation, two naturally occurring lipids are converted into potent agents that target multiple cannabinoid receptors in neurons, interrupting pathways that promote pain and inflammation, researchers report. These modified compounds, called epo-NA5HT and epo-NADA, have much more powerful effects than the molecules from which they are derived, which also regulate pain and inflammation.

Reported in the journal Nature Communications, the study opens a new avenue of research in the effort to find alternatives to potentially addictive opioid pain killers, researchers say.

The ...

Tokyo, Japan - Researchers from Institute of Industrial Science at The University of Tokyo investigated the mechanism of phase separation into the two phases with very different particle mobilities using computer simulations. They found that slow dynamics of complex connected networks control the rate of demixing, which can assist in the design of new functional porous materials, like lithium-ion batteries.

According to the old adage, oil and water don't mix. If you try to do it anyway, you will see the fascinating process of phase separation, in which the two immiscible liquids spontaneously "demix." In this case, the minority phase always forms droplets. Contrary to this, the researchers ...

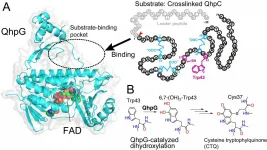

Osaka, Japan - Investigators from the Institute of Scientific and Industrial Research at Osaka University, together with Hiroshima Institute of Technology, have announced the discovery of a new protein that allows an organism to conduct an initial and essential step in converting amino acid residues on a crosslinked polypeptide into an enzyme cofactor. This research may lead to a better understanding of the biochemistry underlying catalysis in cells.

Every living cell is constantly pulsing with an array of biochemical reactions. The rates of these reactions are controlled by special proteins called enzymes, which catalyze specific processes that would otherwise take much longer. A number of enzymes require specialized molecules called "cofactors," which can help shuttle electrons ...

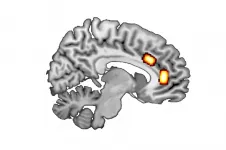

As indicated by other studies, different parts of the brain are responsible for different types of decisions. A research team led by Luca Franziska Kaiser and Prof. Dr. Gerhard Jocham from the HHU working group 'Biological Psychology of Decision Making', and Dr. Theo Gruendler together with colleagues in Magdeburg analysed the balance of the messenger substances GABA and glutamate in two forms of decision-making. The background to the research was to find out how different concentrations of these substances influence the person making the decision.

On the one hand, the researchers looked at 'reward-based decisions', which involve maximising reward by selecting the better of two ...

It is now possible to capture images of planets that could potentially sustain life around nearby stars, thanks to advances reported by an international team of astronomers in the journal Nature Communications.

Using a newly developed system for mid-infrared exoplanet imaging, in combination with a very long observation time, the study's authors say they can now use ground-based telescopes to directly capture images of planets about three times the size of Earth within the habitable zones of nearby stars.

Efforts to directly image exoplanets - planets outside our solar system - have been hamstrung by technological limitations, resulting in a bias toward the detection of easier-to-see planets that are much larger than Jupiter and are located around very young stars and far outside the ...

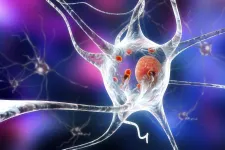

A study published in Nature Communications today (Wednesday 10 February) presents a compelling new evidence about what a key protein called alpha-synuclein actually does in neurons in the brain.

Dr Giuliana Fusco, Research Fellow at St John's College, University of Cambridge, and lead author of the paper, said: "This study could unlock more information about this debilitating neurodegenerative disorder that can leave people unable to walk and talk. If we want to cure Parkinson's, first we need to understand the function of alpha-synuclein, a protein present in everyone's brains. ...

While deforestation levels have decreased significantly since the turn of the 21st century, the United Nations (UN) estimates that 10 million hectares of trees have been felled in each of the last five years.

Aside from their vital role in absorbing CO2 from the air, forests play an integral part in maintaining the delicate ecosystems that cover our planet.

Efforts are now underway across the world to rectify the mistakes of the past, with the UN Strategic Plan for Forests setting out the objective for an increase in global forest coverage by 3% by 2030.

With time being of the essence, one of the most popular methods of reforestation in humid, tropical regions ...