(Press-News.org) Experts from the Natural History Museum, The Francis Crick Institute and the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History Jena have joined together to untangle the different meanings of ancestry in the evolution of our species Homo sapiens.

Most of us are fascinated by our ancestry, and by extension the ancestry of the human species. We regularly see headlines like 'New human ancestor discovered' or 'New fossil changes everything we thought about our ancestry', and yet the meanings of words like ancestor and ancestry are rarely discussed in detail. In the new paper, published in Nature, experts review our current understanding of how modern human ancestry around the globe can be traced into the distant past, and which ancestors it passes through during our journey back in time.

Co-author researcher at the Natural History Museum Prof Chris Stringer said: "Some of our ancestors will have lived in groups or populations that can be identified in the fossil record, whereas very little will be known about others. Over the next decade, growing recognition of our complex origins should expand the geographic focus of paleoanthropological fieldwork to regions previously considered peripheral to our evolution, such as Central and West Africa, the Indian subcontinent and Southeast Asia."

The study identified three key phases in our ancestry that are surrounded by major questions, and which will be frontiers in coming research. From the worldwide expansion of modern humans about 40-60 thousand years ago and the last known contacts with archaic groups such as the Neanderthals and Denisovans, to an African origin of modern human diversity about 60-300,000 years ago, and finally the complex separation of modern human ancestors from archaic human groups about 300,000 to 1 million years ago.

The scientists argue that no specific point in time can currently be identified when modern human ancestry was confined to a limited birthplace, and that the known patterns of the first appearance of anatomical or behavioural traits that are often used to define Homo sapiens fit a range of evolutionary histories.

Co-author Pontus Skoglund from The Francis Crick Institute said: "Contrary to what many believe, neither the genetic or fossil record have so far revealed a defined time and place for the origin of our species. Such a point in time, when the majority of our ancestry was found in a small geographic region and the traits we associate with our species appeared, may not have existed. For now, it would be useful to move away from the idea of a single time and place of origin."

"Following from this, major emerging questions concern which mechanisms drove and sustained this human patchwork, with all its diverse ancestral threads, over time and space," said co-author Eleanor Scerri from the Pan-African Evolution Research Group at the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History. "Understanding the relationship between fractured habitats and shifting human niches will undoubtedly play a key role in unravelling these questions, clarifying which demographic patterns provide a best fit with the genetic and palaeoanthropological record."

The success of direct genetic analyses so far highlights the importance of a wider, ancient genetic record. This will require continued technological improvements in ancient DNA (aDNA) retrieval, biomolecular screening of fragmentary fossils to find unrecognised human material, wider searches for sedimentary aDNA, and improvements in the evolutionary information provided by ancient proteins. Interdisciplinary analysis of the growing genetic, fossil and archaeological records will undoubtedly reveal many new surprises about the roots of modern human ancestry.

INFORMATION:

About the Natural History Museum

The Natural History Museum is both a world-leading science research centre and the most-visited natural history museum in Europe. With a vision of a future in which both people and the planet thrive, it is uniquely positioned to be a powerful champion for balancing humanity's needs with those of the natural world.

It is custodian of one of the world's most important scientific collections comprising over 80 million specimens. The scale of this collection enables researchers from all over the world to document how species have and continue to respond to environmental changes - which is vital in helping predict what might happen in the future and informing future policies and plans to help the planet.

The Museum's 300 scientists continue to represent one of the largest groups in the world studying and enabling research into every aspect of the natural world. Their science is contributing critical data to help the global fight to save the future of the planet from the major threats of climate change and biodiversity loss through to finding solutions such as the sustainable extraction of natural resources.

The Museum uses its enormous global reach and influence to meet its mission to create advocates for the planet - to inform, inspire and empower everyone to make a difference for nature. We welcome over five million visitors each year; our digital output reaches hundreds of thousands of people in over 200 countries each month and our touring exhibitions have been seen by around 30 million people in the last 10 years.

About the Francis Crick Institute

The Francis Crick Institute is a biomedical discovery institute dedicated to understanding the fundamental biology underlying health and disease. Its work is helping to understand why disease develops and to translate discoveries into new ways to prevent, diagnose and treat illnesses such as cancer, heart disease, stroke, infections, and neurodegenerative diseases.

An independent organisation, its founding partners are the Medical Research Council (MRC), Cancer Research UK, Wellcome, UCL (University College London), Imperial College London and King's College London.

The Crick was formed in 2015, and in 2016 it moved into a brand new state-of-the-art building in central London which brings together 1500 scientists and support staff working collaboratively across disciplines, making it the biggest biomedical research facility under a single roof in Europe.

http://crick.ac.uk/

About the Pan-African Evolution Research Group

The Pan-African Evolution Research Group, Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History is an independent research group dedicated to investigating the origins of our species and the parallel transformation of environments and ecosystems. The group's work is unravelling the human story from the perspective of poorly researched regions and environments, coalescing new data and developing novel methods to understand patterns of population movement, cultural change, ecological adaptations, disease, and interactions with now extinct hominins. This research feeds into solutions of current global challenges by contributing lessons from the past to find sustainable solutions to the dual biodiversity and climate crises.

The Pan African Research Group was formed in early 2019 within the framework of the Max Planck Society's flagship Lise Meitner Excellence Programme.

MINNEAPOLIS/ST.PAUL (02/10/2021) -- University of Minnesota Medical School researchers studied SARS-CoV-2 infections at individual cellular levels and made four major discoveries about the virus, including one that validates the effectiveness of remdesivir - an FDA-approved antiviral drug - as a form of treatment for severe COVID-19 disease.

"Since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, the way that each individual responds differently to the infection has been closely studied. In our new study, we examined variations in the way individual cells reacted differently to the coronavirus and responded to antiviral treatment," said Ryan Langlois, PhD, senior author of the study, associate professor in the Department ...

PHILADELPHIA -- Past exposure to seasonal coronaviruses (CoVs), which cause the common cold, does not result in the production of antibodies that protect against the novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2, according to a study led by Scott Hensley, PhD, an associate professor of Microbiology at the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania.

Prior studies have suggested that recent exposure to seasonal CoVs protects against SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19. However, research from Hensley's team, published in Cell, suggests that if there is such protection, it does not come from antibodies.

"We found that many people possessed antibodies that could bind to SARS-CoV-2 before the pandemic, but these antibodies could not prevent infections," Hensley said. ...

Researchers from the University of Basel have developed a virtual reality app for smartphones to reduce fear of heights. Now, they have conducted a clinical trial to study its efficacy. Trial participants who spent a total of four hours training with the app at home showed an improvement in their ability to handle real height situations.

Fear of heights is a widespread phenomenon. Approximately 5% of the general population experiences a debilitating level of discomfort in height situations. However, the people affected rarely take advantage of the available treatment options, such as exposure therapy, which involves putting the person in the anxiety-causing situation under the guidance of a professional. On the one hand, people ...

Rituximab, an anti-cancer drug targeting the membrane protein CD20, was the first approved therapeutic antibody against B tumor cells. Immunologists at the University of Freiburg have now solved a mystery about how it works. A team headed by Professor Dr. Michael Reth used cell cultures, healthy cells, and cells from cancer patients to investigate how CD20 organizes the nanostructures on the B cell membrane. If the protein is missing or Rituximab binds to it, the organization of the B cell surface changes. The resting B cell is activated in the process. The team has published the research in the journal PNAS as part of contributions by new members of the National Academy of Science.

B cells are white blood cells and part of the immune system. When they recognize ...

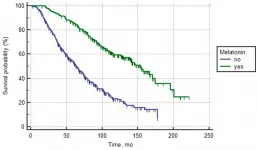

Oncotarget recently published "Melatonin increases overall survival of prostate cancer patients with poor prognosis after combined hormone radiation treatment" which reported that a retrospective study included 955 patients of various stages of prostate cancer who received combined hormone radiation treatment from 2000 to 2019. Comprehensive statistical methods were used to analyze the overall survival rate of PCa patients treated with melatonin in various prognosis groups.

The overall survival rate of PCa patients with favorable and intermediate prognoses treated or not treated ...

JACKSONVILLE, Fla. (February 10, 2021) - Brain volume, verbal IQ, and overall IQ are lower in children with Type 1 diabetes (T1D) than in children without diabetes, according to a new longitudinal study published in Diabetes Care, a journal of the American Diabetes Association. The nearly eight-year study, led by Nelly Mauras, MD, a clinical research scientist at Nemours Children's Health System in Jacksonville, Florida, and Allan Reiss MD, a Professor at the Stanford University School of Medicine in California, compared brain scans of young children who have T1D with those of non-diabetic children to assess the extent to which glycemic exposure may adversely affect the ...

It was reported that volume of the brain areas such as superior temporal gyrus and anterior cingulate cortex reduces in schizophrenia but precise change of three-dimensional structure of neuron has remains unclear.

Dr. Itokawa and colleague performed Nanotomography experiments using Fresnel zone plate optics at the BL37XU beamline of the SPring-8 synchrotron radiation facility and at the 32-ID beamline of the Advanced Photon Source (APS) of Argonne National Laboratory.

A total of 34 three-dimensional image datasets of layer V of the BA22 cortex were blinded ...

The recent review, published in Environment International and led by the University of Tartu, summarises the effect of aquatic pollution on cancer prevalence in wild animals with the help of more than 300 reviewed studies. Authors shed light on understudied yet important fields in cancer research in wild animals - summarising the key effects and pointing to future research avenues to crack the puzzle of why cancer develops in polluted environments.

„What was immediately evident was the bias towards fish in current research into aquatic wildlife cancer. However, given this bias it is especially interesting ...

Sophia Antipolis, 10 February 2021: A nationwide US study has found increasing death rates from heart disease in women under 65. The research is published in European Heart Journal - Quality of Care and Clinical Outcomes, a journal of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC).1 The study found that while death rates from cancer declined every year between 1999 and 2018, after an initial drop, heart disease death rates have been rising since 2010.

"Young women in the US are becoming less healthy, which is now reversing prior improvements in heart disease deaths," said senior author Dr. Erin Michos of Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, US. "With ...

Satellite images reveal that the timing of algal blooms in the Red Sea may affect the next haul of sardines and squid by commercial fisheries.

Rising temperatures in the Red Sea have changed the timing of phytoplankton blooms. These microscopic algae form the base of many marine food webs and so are critical to ocean biodiversity and the industries that they support on land, such as fisheries and tourism.

A team led by KAUST climate modeler Ibrahim Hoteit has used satellite images to study the phenology of algal blooms in the northern Red Sea and ...