(Press-News.org) The golden-mantled ground squirrel (Callospermophilus lateralis) is a popular sight among tourists in the Rocky Mountains--the small rodent is a photogenic creature with a striped back and pudgy cheeks that store seeds and other food.

But there's a reality that Instagram photos don't capture, said Christy McCain, an ecologist at the University of Colorado Boulder. In a new study spanning nearly 13 years, she and her colleagues discovered that the ground squirrel has joined many other small mammals in Colorado's Rocky Mountains that are making an ominous trek: They're climbing uphill to avoid warming temperatures in the state brought on by climate change.

"It's frightening," said McCain, an associate professor in the Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology. "We've been talking about climate change in the Rockies for a long time, but I think we can say that this is a sign that things are now responding and responding quite drastically."

The golden-mantled ground squirrel, which is often confused for a chipmunk, lives in conifer forests in the Rockies and several other western mountain ranges.

"It is likely one of the most photographed mammals in Rocky Mountain National Park as it poses and preens on rocks near the roadside and in campgrounds," said McCain, also curator of vertebrates at the CU Museum of Natural History. "They hibernate in winter, are territorial in the summer, and they make distinctive alarm calls to notify each other of nearby dangers."

Her latest research, published this week in the journal Ecology, takes a deep dive into the squirrel's fate, and that of 46 other species of small mammals from the Front Range and San Juan Rockies--from mice to shrews and even the yellow-bellied marmot (Marmota flaviventris).

The team reports that, on average, the ranges of these critters seem to have shifted by more than 400 feet up in elevation since the 1980s. Montane mammals, or those already living at higher elevations like the ground squirrel, have taken the biggest brunt--moving up by 1,100 feet on average. It's a significant change that, if it continues, could wind up squeezing many of these animals out of Colorado entirely.

And while many of these small creatures won't ever show up on Colorado postcards, McCain said that they may be bellwethers for larger and increasingly urgent changes in the Rocky Mountains.

Passion for mountains

For McCain, the project is, in many ways, a culmination of her lifelong love of mountains.

It began in the mid-1990s when she was serving in the Peace Corps in Honduras. There, McCain was taken by how much the tropical nation's mountains resembled layer cakes: As she climbed up in elevation, mountain ecosystems transformed around her, sometimes dramatically.

"Every place you went to, there were completely different birds," she said. "The changes are so stark."

But that layer cake nature may also be the downfall of mountain ecosystems in the face of climate change. Colorado has warmed by nearly 3.5 degrees Fahrenheit since the 1980s because of human-caused climate change. As the state heats up, many scientists have predicted that ponderosa pine forests and other mountain ecosystems will have to move higher to find cooler weather. Some animals, and even entire communities, may be pushed to the tops of mountains with nowhere else to go.

McCain and her colleagues wanted to find out if that upward shift was already happening in the Rockies.

Beginning in 2008, her team visited multiple sites in Colorado's Front Range and San Juan mountains to collect records of the current ranges of 47 species of rodents and shrews. They included rare animals, such as the pygmy shrew (Sorex hoyi), which weighs less than a quarter and ranks as North America's smallest mammal. The endangered Preble's jumping mouse (Zapus hudsonius preblei), known for its long tail and big feet that are useful for swimming, also made the list. In some cases, McCain said, the habitats were so remote that the researchers traveled using horse trains to carry their equipment.

"We had to get used to really unpleasant conditions," McCain said. "We put up with being wet in the mountains and being hot in the desert, flash floods and lightning storms."

The group then compared the findings from their surveys to roughly 4,500 historic records from museum collections in the Front Range and San Juan mountains dating back to the 1880s. They included animals stored in CU Boulder's own museum, which houses nearly 12,000 mammal specimens from Colorado.

Drastic action

The results showed a complex response to climate change and other pressures. Some of the animals in the survey, McCain said, moved down in elevation, not up, while others actually saw their ranges increase since the 1980s.

But most of the study mammals shifted uphill--and not by a small amount. That was especially true for those already living at high elevations. Before 1980, the pygmy shrew, for example, was never detected above 9,800 feet in elevation. Today, its maximum extent is more than 11,800 feet. The golden-mantled ground squirrel similarly hiked up by 650 feet, or 200 meters, in the Front Range and 2,300 feet, or 700 meters, in the San Juans.

"I was expecting that we would see something between 100 to 200 meters, but we saw a lot more," McCain said. "This is way bigger than the change that has been determined in other mountain regions around the world."

The study, McCain said, paints a stark picture of a mountain range in crisis. But it's one with a silver lining: There may still be time to protect the West's iconic ponderosa pine forests, alpine meadows and scraggly tundra--but only if Coloradans and people around the world act now to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions.

"It's a wake-up call," McCain said. "We have to start taking this seriously immediately if we want to have healthy mountains and ecosystems."

INFORMATION:

Other coauthors on the new study include Tim Szewczyk, a former graduate student at CU Boulder now at the University of Lausanne, and Sarah King of Colorado State University.

Globular clusters are extremely dense stellar systems, in which stars are packed closely together. They are also typically very old -- the globular cluster that is the focus of this study, NGC 6397, is almost as old as the Universe itself. It resides 7800 light-years away, making it one of the closest globular clusters to Earth. Because of its very dense nucleus, it is known as a core-collapsed cluster.

When Eduardo Vitral and Gary A. Mamon of the Institut d'Astrophysique de Paris set out to study the core of NGC 6397, they expected to find evidence for an "intermediate-mass" black hole (IMBH). These are smaller than the supermassive black holes that lie at the cores of large galaxies, but larger than stellar-mass black holes ...

Rheumatic heart disease (RHD) develops as a long term complication of childhood streptococcal angina. Latent RHD can be detected with echocardiography years before it becomes symptomatic. RHD is curable when treated early with medication.

RHD is responsible for over 300 000 deaths worldwide each year, accounting for just over two-thirds of all deaths from valvular heart diseases. RHD is disproportionally prevalent across sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia and the Pacific Islands and largely a phenomenon of marginalized communities in developing and emerging countries whereas ...

Millions of tonnes of plastic waste find their way into the ocean every year. A team of researchers from the Institute for Advanced Sustainability Studies (IASS) in Potsdam has investigated the role of regional ocean governance in the fight against marine plastic pollution, highlighting why regional marine governance should be further strengthened as negotiations for a new global agreement continue.

In recent years, images of whales and sea turtles starving to death after ingesting plastic waste or becoming entangled in so-called ghost nets have led to a growing ...

Domestic cats are a major threat to wild species, including birds and small mammals. But researchers reporting in the journal Current Biology on February 11 now have evidence that some simple strategies can help to reduce cats' environmental impact without restricting their freedom. Their studies show that domestic cats hunt less when owners feed them a diet including plenty of meat proteins. Equally, it helps to play with them each day in ways that allow cats to mimic hunting.

"While keeping cats indoors is the only sure-fire way to prevent hunting, some owners ...

Domestic cats hunt wildlife less if owners play with them daily and feed them a meat-rich food, new research shows.

Hunting by cats is a conservation and welfare concern, but methods to reduce this are controversial and often rely on restricting cat behaviour in ways many owners find unacceptable.

The new study - by the University of Exeter - found that introducing a premium commercial food where proteins came from meat reduced the number of prey animals cats brought home by 36%, and also that five to ten minutes of daily play with an owner resulted ...

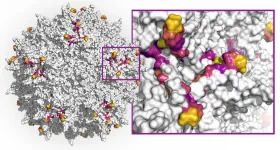

Cambridge, MA - February 11, 2020 - Dyno Therapeutics, a biotech company applying artificial intelligence (AI) to gene therapy, today announced a publication in Nature Biotechnology that demonstrates the use of artificial intelligence to generate an unprecedented diversity of adeno-associated virus (AAV) capsids towards identifying functional variants capable of evading the immune system, a factor that is critical to enabling all patients to benefit from gene therapies. The research was conducted in collaboration with Google Research, Harvard's Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering and the Harvard Medical School laboratory of George M. Church, Ph.D., a Dyno scientific co-founder. The publication is entitled "Deep diversification ...

Natural compounds found in apples and other fruits may help stimulate the production of new brain cells, which may have implications for learning and memory, according to a END ...

(Boston) -- Adeno-associated viruses (AAVs) have become promising vehicles for delivering gene therapies to defective tissues in the human body because they are non-pathogenic and can transfer therapeutic DNA into target cells. However, while the first gene therapy products approved by the Federal Drug Administration (FDA) use AAV vectors and others are likely to follow, AAV vectors still have not reached their full potential to meet gene therapeutic challenges.

First, currently used AAV capsids - the spherical protein structures enveloping the virus' single-stranded DNA genome which can be modified to encode therapeutic genes - are limited in their ability to specifically hone in on the tissue affected by a disease and their wider distribution throughout ...

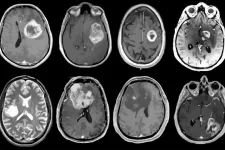

Glioblastoma is among the most aggressive and devastating of cancers. While rare compared with other cancers, it's the most common type of brain cancer. Even with intensive therapy, relatively few patients survive longer than two years after diagnosis, and fewer than 10% of patients survive beyond five years. Despite extensive studies focused on genomic features of glioblastoma, relatively little progress has been made in improving treatment for patients with this deadly disease.

Now, a new study led by Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, Case Western Reserve University and the National Cancer Institute (NCI) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) has revealed a detailed map of the genes, ...

What The Study Did: This observational study assessed CRISPR-based methods for screening to detect SARS-CoV-2 among asymptomatic college students.

Authors: Carolina Arias, Ph.D., of the University of California, Santa Barbara, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.37129)

Editor's Note: The article includes funding/support disclosures. Please see the article for additional information, including other authors, author contributions and affiliations, conflict of interest and financial disclosures, and funding and support.

INFORMATION:

Media advisory: ...