(Press-News.org) EUGENE, Ore. -- Feb. 11, 2021 -- Researchers have mined and combined information from two databases to link pollen and key plant traits to generate confidence in the ability to reconstruct past ecosystem services.

The approach provides a new tool to that can be used to understand how plants performed different benefits useful for humans over the past 21,000 years, and how these services responded to human and climate disturbances, including droughts and fires, said Thomas Brussel, a postdoctoral researcher in the University of Oregon's Department of Geography.

The approach is detailed in a paper published online Jan. 13 in the journal Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution.

Ultimately, Brussel said, the combined information could enhance decisions about conservation to allow regional ecosystem managers to continue to provide goods and services, such as having plants that protect hillsides from erosion or help purify water, based on their relationship with climate changes in the past.

For example, he said, an ecosystem's history may indicate that plants have previously withstood similar disruptions and could continue to thrive through preservation techniques.

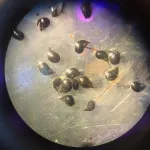

Pollen cores have long helped scientists study environmental and ecological changes in a given location that have occurred because of climate changes and wildfires over recent geologic time. Combining pollen records to plant traits provides a picture of how well ecosystems have functioned under different scenarios, Brussel said.

"The biggest finding in this study is that researchers can now be confident that transforming pollen into the processes that ecosystems undergo works," he said. "With this information, we can now explore new questions that were previously unanswerable and provide positive guidance on how we can conserve and manage landscapes and biodiversity."

Brussel began pursuing the approach as a doctoral student at the University of Utah in the emerging field of functional paleoecology. Initial reception to the approach, when presented at conferences, drew interest but also calls for proof that the idea is possible, Brussel said. The paper, co-authored with his Utah mentor Simon Christopher Brewer, provides a proof-of-concept that his approach works.

For the study, Brussel and Brewer merged publicly available records for surface pollen samples found in the Neotoma Paleoecology Database and plant traits, specifically leaf area, plant height and seed mass, from the Botanical Information and Ecology Network.

They then restricted their results to only plants native to ecosystems from Mexico to Canada by combing through the U.S. Department of Agriculture's PLANTS Database and a compilation of all native plants in Mexico.

The resulting data for North America covers some 1,300 individual sites and includes 9.5 million plant height measurements for 2,146 species, 13,103 leaf area details from 1,016 species, and 16,621 seed mass data from 3,580 species.

The information, Brussel said, provides extensive details on the fitness of ecosystems that should help researchers study the mechanisms of changes in carbon or water cycling related to climate change.

"Our work is extremely relevant to modern climate change," he said. "The past houses all these natural experiments. The data are there. We can use that data as parallels for what may happen in the future. Using trait-based information through this approach, we can gain new insight, with confidence, that we haven't been able to get at before now."

At the UO, Brussel is working with Melissa Lucash, a research assistant professor who studies large, forested landscapes with a focus on the impacts of climate change and wildfires. Brussel is part of Lucash's research on potential climate changes being faced by Siberia's boreal forests and tundra.

He also is applying his approach to potential conservation and management strategies for some of the world's biodiversity hotspots, which are seeing a decline in plant species and wildlife as a result of global change.

"Using the newly validated approach, my idea is to assess the severity of the biodiversity degradation that has been occurring in these regions over recent millennia," Brussel said. "My end goal is to create a list of regions that can be prioritized for hotspot conservation, based on how severe an ecosystem's services have declined over time."

INFORMATION:

Media Contact:

Jim Barlow,

director of science and research communications,

541-346-3481,

jebarlow@uoregon.edu

Links:

About Thomas Brussel:

https://www.melissalucash.com/tombrussel

UO Department of Geography:

https://geography.uoregon.edu/

Palo Alto, CA-- Understanding how plants respond to stressful environmental conditions is crucial to developing effective strategies for protecting important agricultural crops from a changing climate. New research led by Carnegie's Zhiyong Wang, Shouling, Xu, and Yang Bi reveals an important process by which plants switch between amplified and dampened stress responses. Their work is published by Nature Communications.

To survive in a changing environment, plants must choose between different response strategies, which are based on both external environmental factors and internal nutritional and energy demands. For example, a plant might either delay or accelerate its lifecycle, depending on the availability of the stored ...

A negative experience with food usually leaves us unable to stomach the thought of eating that particular dish again. Using sugar-loving snails as models, researchers at the University of Sussex believe these bad experiences could be causing a switch in our brains, which impacts our future eating habits.

Like many other animals, snails like sugar and usually start feeding on it as soon as it is presented to them. But through aversive training which involved tapping the snails gently on the head when sugar appeared, the snails' behaviour was altered and they refused to feed on the sugar, even when hungry.

When the team ...

FRANKFURT. More than two thirds of the earth is covered by clouds. Depending on whether they float high or low, how large their water and ice content is, how thick they are or over which region of the Earth they form, it gets warmer or cooler underneath them. Due to human influence, there are most likely more cooling effects from clouds today than in pre-industrial times, but how clouds contribute to climate change is not yet well understood. Researchers currently believe that low clouds over the Arctic and Antarctic, for example, contribute to the warming of these regions by blocking the direct radiation of long-wave heat from the Earth's surface.

All ...

Low-income middle-aged African-American women with high blood pressure very commonly suffer from depression and should be better screened for this serious mental health condition, according to a study led by researchers at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

The researchers found that in a sample of over 300 low-income, African-American women, aged 40-75, with uncontrolled hypertension, nearly 60 percent screened positively for a diagnosis of depression based on a standard clinical questionnaire about depressive symptoms.

The results appeared February 10 in JAMA Psychiatry.

"Our findings suggest that low-income, middle-aged African-American women with hypertension really should be screened for depression symptoms," ...

CHAMPAIGN, Ill. -- People who participated in a health education program that included both mental health and physical health information significantly reduced their risks of cardiovascular disease and other chronic diseases by the end of the 12-month intervention - and sustained most of those improvements six months later, researchers found.

People who participated in the integrated mental and physical health program maintained significant improvements on seven of nine health measures six months after the program's conclusion. These included, on average, a 21% ...

New research shows that biodiversity is important not just at the traditional scale of short-term plot experiments--in which ecologists monitor the health of a single meadow, forest grove, or pond after manipulating its species counts--but when measured over decades and across regional landscapes as well. The findings can help guide conservation planning and enhance efforts to make human communities more sustainable.

Published in a recent issue of Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, the multi-institutional study was led by Dr. Christopher Patrick ...

STEMOs (Stroke-Einsatz-Mobile) have been serving Berlin for ten years. The specialized stroke emergency response vehicles allow physicians to start treating stroke patients before they reach hospital. For the first time, a team of researchers from Charité - Universitätsmedizin Berlin has been able to show that the dispatch of mobile stroke units is linked to improved clinical outcomes. The researchers' findings, which show that patients for whom STEMOs were dispatched were more likely to survive without long-term disability, have been published in JAMA*.

The phrase 'time is brain' emphasizes a fundamental principle from emergency medicine, namely that after stroke, every minute counts. Without ...

With the help of the international Gemini Observatory, a Program of NSF's NOIRLab, and other ground-based telescopes, astronomers have confirmed that a faint object discovered in 2018 and nicknamed "Farfarout" is indeed the most distant object yet found in our Solar System. The object has just received its designation from the International Astronomical Union.

Farfarout was first spotted in January 2018 by the Subaru Telescope, located on Maunakea in Hawai'i. Its discoverers could tell it was very far away, but they weren't sure exactly how far. They needed more observations.

"At that time we did not know the object's orbit as we only had the Subaru discovery observations over 24 hours, but it takes years of ...

A report summary released today by a team at Lehigh University led by Thomas McAndrew , a computational scientist and assistant professor in Lehigh's College of Health, shares the consensus results of experts in the modeling of infectious disease when asked to rank the top 5 most effective interventions to mitigate the spread and impact of COVID-19 in the U.S.

The report is part of an ongoing meta forecasting project aimed at translating forecasting and real world experience into actions.

McAndrew and his colleagues wanted to answer "Here is where ...

Wilmington, DE, Feb. 11, 2020 -Scientists have developed an affordable, downloadable app that scans for potential unintended mistakes when CRISPR is used to repair mutations that cause disease. The app reveals potentially risky DNA alterations that could impede efforts to safely use CRISPR to correct mutations in conditions like sickle cell disease and cystic fibrosis. The development of the new tool, called DECODR (which stands for Deconvolution of Complex DNA Repair), was reported today in The CRISPR Journal by researchers from ChristianaCare's Gene Editing Institute.

"Our research has shown that when CRISPR is used to repair a gene, it also can introduce a variety of subtle changes to DNA near the site of the repair," said Eric ...