(Press-News.org) Long held in a private collection, the newly analysed tooth of an approximately 9-year-old Neanderthal child marks the hominin's southernmost known range. Analysis of the associated archaeological assemblage suggests Neanderthals used Nubian Levallois technology, previously thought to be restricted to Homo sapiens.

With a high concentration of cave sites harbouring evidence of past populations and their behaviour, the Levant is a major centre for human origins research. For over a century, archaeological excavations in the Levant have produced human fossils and stone tool assemblages that reveal landscapes inhabited by both Neanderthals and Homo sapiens, making this region a potential mixing ground between populations. Distinguishing these populations by stone tool assemblages alone is difficult, but one technology, the distinct Nubian Levallois method, is argued to have been produced only by Homo sapiens.

In a new study published in Scientific Reports, researchers from the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History teamed up with international partners to re-examine the fossil and archaeological record of Shukbah Cave. Their findings extend the southernmost known range of Neanderthals and suggest that our now-extinct relatives made use of a technology previously argued to be a trademark of modern humans. This study marks the first time the lone human tooth from the site has been studied in detail, in combination with a major comparative study examining the stone tool assemblage.

"Sites where hominin fossils are directly associated with stone tool assemblages remain a rarity - but the study of both fossils and tools is critical for understanding hominin occupations of Shukbah Cave and the larger region," says lead author Dr Jimbob Blinkhorn, formerly of Royal Holloway, University of London and now with the Pan-African Evolution Research Group (Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History).

Shukbah Cave was first excavated in the spring of 1928 by Dorothy Garrod, who reported a rich assemblage of animal bones and Mousterian-style stone tools cemented in breccia deposits, often concentrated in well-marked hearths. She also identified a large, unique human molar. However, the specimen was kept in a private collection for most of the 20th century, prohibiting comparative studies using modern methods. The recent re-identification of the tooth at the Natural History Museum in London has led to new detailed work on the Shukbah collections.

"Professor Garrod immediately saw how distinctive this tooth was. We've examined the size, shape and both the external and internal 3D structure of the tooth, and compared that to Holocene and Pleistocene Homo sapiens and Neanderthal specimens. This has enabled us to clearly characterise the tooth as belonging to an approximately 9 year old Neanderthal child," says Dr. Clément Zanolli, from Université de Bordeaux. "Shukbah marks the southernmost extent of the Neanderthal range known to date," adds Zanolli.

Although Homo sapiens and Neanderthals shared the use of a wide suite of stone tool technologies, Nubian Levallois technology has recently been argued to have been exclusively used by Homo sapiens. The argument has been made particularly in southwest Asia, where Nubian Levallois tools have been used to track human dispersals in the absence of fossils.

"Illustrations of the stone tool collections from Shukbah hinted at the presence of Nubian Levallois technology so we revisited the collections to investigate further. In the end, we identified many more artefacts produced using the Nubian Levallois methods than we had anticipated," says Blinkhorn. "This is the first time they've been found in direct association with Neanderthal fossils, which suggests we can't make a simple link between this technology and Homo sapiens."

"Southwest Asia is a dynamic region in terms of hominin demography, behaviour and environmental change, and may be particularly important to examine interactions between Neanderthals and Homo sapiens," adds Prof Simon Blockley, of Royal Holloway, University of London. "This study highlights the geographic range of Neanderthal populations and their behavioural flexibility, but also issues a timely note of caution that there are no straightforward links between particular hominins and specific stone tool technologies."

"Up to now we have no direct evidence of a Neanderthal presence in Africa," said Prof Chris Stringer of the Natural History Museum. "But the southerly location of Shukbah, only about 400 km from Cairo, should remind us that they may have even dispersed into Africa at times."

INFORMATION:

Partnerships

Researchers involved in this study include scholars from the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History, Royal Holloway, University of London, the Université de Bordeaux, the Max Planck Institute for Chemical Ecology, the University of Malta, and the Natural History Museum, London. This work was supported by the Leverhulme trust (RPH-2017-087).

A recent study finds that the invasive spotted wing drosophila (Drosophila suzukii) prefers to lay its eggs in places that no other spotted wing flies have visited. The finding raises questions about how the flies can tell whether a piece of fruit is virgin territory - and what that might mean for pest control.

D. suzukii is a fruit fly that is native to east Asia, but has spread rapidly across North America, South America, Africa and Europe over the past 10-15 years. The pest species prefers to lay its eggs in ripe fruit, which poses problems for fruit growers, since consumers don't want to buy infested fruit.

To avoid consumer rejection, there are extensive measures in place to avoid infestation, and to prevent infested ...

Aalto researchers have used an IBM quantum computer to explore an overlooked area of physics, and have challenged 100 year old cherished notions about information at the quantum level.

The rules of quantum physics - which govern how very small things behave - use mathematical operators called Hermitian Hamiltonians. Hermitian operators have underpinned quantum physics for nearly 100 years but recently, theorists have realized that it is possible to extend its fundamental equations to making use of Hermitian operators that are not Hermitian. The new equations describe a universe with its own peculiar set of rules: for example, by looking in the ...

It was tens of miles wide and forever changed history when it crashed into Earth about 66 million years ago.

The Chicxulub impactor, as it's known, left behind a crater off the coast of Mexico that spans 93 miles and goes 12 miles deep. Its devastating impact brought the reign of the dinosaurs to an abrupt and calamitous end by triggering their sudden mass extinction, along with the end of almost three-quarters of the plant and animal species then living on Earth.

The enduring puzzle has always been where the asteroid or comet that set off the destruction originated, and how it came to strike the Earth. And ...

The UK's commercial fishing industry is currently experiencing a number of serious challenges.

However, a study by the University of Plymouth has found that managing the density of crab and lobster pots at an optimum level increases the quality of catch, benefits the marine environment and makes the industry more sustainable in the long term.

Published today in Scientific Reports, a journal published by the Nature group, the findings are the result of an extensive and unprecedented four-year field study conducted in partnership with local fishermen off the coast of southern England.

Over a sustained period, researchers exposed sections of the seabed to differing densities of pot fishing and monitored any impacts using a combination of underwater videos and catch ...

It forever changed history when it crashed into Earth about 66 million years ago.

The Chicxulub impactor, as it's known, left behind a crater off the coast of Mexico that spans 93 miles and runs 12 miles deep. Its devastating impact brought the reign of the dinosaurs to an abrupt and calamitous end by triggering their sudden mass extinction, along with the end of almost three-quarters of the plant and animal species living on Earth.

The enduring puzzle: Where did the asteroid or comet originate, and how did it come to strike Earth? Now, a pair of researchers at the Center for Astrophysics | Harvard & Smithsonian believe they have the answer.

In a study published today in Nature's Scientific Reports, Harvard University ...

When the Covid-19 pandemic struck in early 2020, doctors and researchers rushed to find effective treatments. There was little time to spare. "Making new drugs takes forever," says Caroline Uhler, a computational biologist in MIT's Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science and the Institute for Data, Systems and Society, and an associate member of the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard. "Really, the only expedient option is to repurpose existing drugs."

Uhler's team has now developed a machine learning-based approach to identify drugs already on the market that could ...

A new study finds that California's commuters are likely inhaling chemicals at levels that increase the risk for cancer and birth defects.

As with most chemicals, the poison is in the amount. Under a certain threshold of exposure, even known carcinogens are not likely to cause cancer. Once you cross that threshold, the risk for disease increases.

Governmental agencies tend to regulate that threshold in workplaces. However, private spaces such as the interior of our cars and living rooms are less studied and less regulated.

Benzene and formaldehyde -- both used in automobile manufacturing -- are known to cause cancer at or above certain levels of ...

Far underneath the ice shelves of the Antarctic, there's more life than expected, finds a recent study in the journal Frontiers in Marine Science.

During an exploratory survey, researchers drilled through 900 meters of ice in the Filchner-Ronne Ice Shelf, situated on the south eastern Weddell Sea. At a distance of 260km away from the open ocean, under complete darkness and with temperatures of -2.2°C, very few animals have ever been observed in these conditions.

But this study is the first to discover the existence of stationary animals - similar to sponges and potentially several previously unknown species - attached to a boulder on the sea floor.

"This discovery is one of those ...

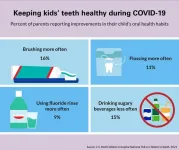

ANN ARBOR, Mich. - A third of parents say the COVID-19 pandemic has made it difficult to get dental care for their children, a new national poll suggests.

But some families may face greater challenges than others. Inability to get a dentist appointment during the pandemic was three times as common for children with Medicaid versus those with private dental coverage, according to the C.S. Mott Children's Hospital National Poll on Children's Health at Michigan Medicine.

"Regular preventive dental care helps keep children's teeth healthy and allows providers to address any tooth decay ...

We find routes to destination and remember special places because there is an area somewhere in the brain that functions like a GPS and navigation system. When taking a new path for the first time, we pay attention to the landmarks along the way. Owing to such navigation system, it becomes easier to find destinations along the path after having already used the path. Over the years, scientists have learned, based on a variety of animal experiments, that cells in the brain region called hippocampus are responsible for spatial perception and are activated in discrete positions ...