(Press-News.org) It was tens of miles wide and forever changed history when it crashed into Earth about 66 million years ago.

The Chicxulub impactor, as it's known, left behind a crater off the coast of Mexico that spans 93 miles and goes 12 miles deep. Its devastating impact brought the reign of the dinosaurs to an abrupt and calamitous end by triggering their sudden mass extinction, along with the end of almost three-quarters of the plant and animal species then living on Earth.

The enduring puzzle has always been where the asteroid or comet that set off the destruction originated, and how it came to strike the Earth. And now a pair of Harvard researchers believe they have the answer.

In a study published in Scientific Reports, Avi Loeb, Frank B. Baird Jr. Professor of Science at Harvard, and Amir Siraj '21, an astrophysics concentrator, put forth a new theory that could explain the origin and journey of this catastrophic object and others like it.

Using statistical analysis and gravitational simulations, Loeb and Siraj show that a significant fraction of a type of comet originating from the Oort cloud, a sphere of debris at the edge of the solar system, was bumped off-course by Jupiter's gravitational field during its orbit and sent close to the sun, whose tidal force broke apart pieces of the rock. That increases the rate of comets like Chicxulub (pronounced Chicks-uh-lub) because these fragments cross the Earth's orbit and hit the planet once every 250 to 730 million years or so.

"Basically, Jupiter acts as a kind of pinball machine," said Siraj, who is also co-president of Harvard Students for the Exploration and Development of Space and is pursuing a master's degree at the New England Conservatory of Music. "Jupiter kicks these incoming long-period comets into orbits that bring them very close to the sun."

It's because of this that long-period comets, which take more than 200 years to orbit the sun, are called sun grazers, he said.

"When you have these sun grazers, it's not so much the melting that goes on, which is a pretty small fraction relative to the total mass, but the comet is so close to the sun that the part that's closer to the sun feels a stronger gravitational pull than the part that is farther from the sun, causing a tidal force" he said. "You get what's called a tidal disruption event and so these large comets that come really close to the sun break up into smaller comets. And basically, on their way out, there's a statistical chance that these smaller comets hit the Earth."

The calculations from Loeb and Siraj's theory increase the chances of long-period comets impacting Earth by a factor of about 10, and show that about 20 percent of long-period comets become sun grazers. That finding falls in line with research from other astronomers.

The pair claim that their new rate of impact is consistent with the age of Chicxulub, providing a satisfactory explanation for its origin and other impactors like it.

"Our paper provides a basis for explaining the occurrence of this event," Loeb said. "We are suggesting that, in fact, if you break up an object as it comes close to the sun, it could give rise to the appropriate event rate and also the kind of impact that killed the dinosaurs."

Loeb and Siraj's hypothesis might also explain the makeup of many of these impactors.

"Our hypothesis predicts that other Chicxulub-size craters on Earth are more likely to correspond to an impactor with a primitive (carbonaceous chondrite) composition than expected from the conventional main-belt asteroids," the researchers wrote in the paper.

This is important because a popular theory on the origin of Chicxulub claims the impactor is a fragment of a much larger asteroid that came from the main belt, which is an asteroid population between the orbit of Jupiter and Mars. Only about a tenth of all main-belt asteroids have a composition of carbonaceous chondrite, while it's assumed most long-period comets have it. Evidence found at the Chicxulub crater and other similar craters that suggests they had carbonaceous chondrite.

This includes an object that hit about 2 billion years ago and left the Vredefort crater in South Africa, which is the largest confirmed crater in Earth's history, and the impactor that left the Zhamanshin crater in Kazakhstan, which is the largest confirmed crater within the last million years.

The researchers say that composition evidence supports their model and that the years the objects hit support both their calculations on impact rates of Chicxulub-sized tidally disrupted comets and for smaller ones like the impactor that made the Zhamanshin crater. If produced the same way, they say those would strike Earth once every 250,000 to 730,000 years.

Loeb and Siraj say their hypothesis can be tested by further studying these craters, others like them, and even ones on the surface of the moon to determine the composition of the impactors. Space missions sampling comets can also help.

Aside from composition of comets, the new Vera Rubin Observatory in Chile may be able to see the tidal disruption of long-period comets after it becomes operational next year.

"We should see smaller fragments coming to Earth more frequently from the Oort cloud," Loeb said. "I hope that we can test the theory by having more data on long-period comets, get better statistics, and perhaps see evidence for some fragments."

Loeb said understanding this is not just crucial to solving a mystery of Earth's history but could prove pivotal if such an event were to threaten the planet again.

"It must have been an amazing sight, but we don't want to see that side," he said.

INFORMATION:

The UK's commercial fishing industry is currently experiencing a number of serious challenges.

However, a study by the University of Plymouth has found that managing the density of crab and lobster pots at an optimum level increases the quality of catch, benefits the marine environment and makes the industry more sustainable in the long term.

Published today in Scientific Reports, a journal published by the Nature group, the findings are the result of an extensive and unprecedented four-year field study conducted in partnership with local fishermen off the coast of southern England.

Over a sustained period, researchers exposed sections of the seabed to differing densities of pot fishing and monitored any impacts using a combination of underwater videos and catch ...

It forever changed history when it crashed into Earth about 66 million years ago.

The Chicxulub impactor, as it's known, left behind a crater off the coast of Mexico that spans 93 miles and runs 12 miles deep. Its devastating impact brought the reign of the dinosaurs to an abrupt and calamitous end by triggering their sudden mass extinction, along with the end of almost three-quarters of the plant and animal species living on Earth.

The enduring puzzle: Where did the asteroid or comet originate, and how did it come to strike Earth? Now, a pair of researchers at the Center for Astrophysics | Harvard & Smithsonian believe they have the answer.

In a study published today in Nature's Scientific Reports, Harvard University ...

When the Covid-19 pandemic struck in early 2020, doctors and researchers rushed to find effective treatments. There was little time to spare. "Making new drugs takes forever," says Caroline Uhler, a computational biologist in MIT's Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science and the Institute for Data, Systems and Society, and an associate member of the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard. "Really, the only expedient option is to repurpose existing drugs."

Uhler's team has now developed a machine learning-based approach to identify drugs already on the market that could ...

A new study finds that California's commuters are likely inhaling chemicals at levels that increase the risk for cancer and birth defects.

As with most chemicals, the poison is in the amount. Under a certain threshold of exposure, even known carcinogens are not likely to cause cancer. Once you cross that threshold, the risk for disease increases.

Governmental agencies tend to regulate that threshold in workplaces. However, private spaces such as the interior of our cars and living rooms are less studied and less regulated.

Benzene and formaldehyde -- both used in automobile manufacturing -- are known to cause cancer at or above certain levels of ...

Far underneath the ice shelves of the Antarctic, there's more life than expected, finds a recent study in the journal Frontiers in Marine Science.

During an exploratory survey, researchers drilled through 900 meters of ice in the Filchner-Ronne Ice Shelf, situated on the south eastern Weddell Sea. At a distance of 260km away from the open ocean, under complete darkness and with temperatures of -2.2°C, very few animals have ever been observed in these conditions.

But this study is the first to discover the existence of stationary animals - similar to sponges and potentially several previously unknown species - attached to a boulder on the sea floor.

"This discovery is one of those ...

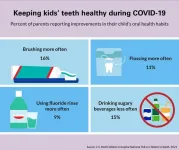

ANN ARBOR, Mich. - A third of parents say the COVID-19 pandemic has made it difficult to get dental care for their children, a new national poll suggests.

But some families may face greater challenges than others. Inability to get a dentist appointment during the pandemic was three times as common for children with Medicaid versus those with private dental coverage, according to the C.S. Mott Children's Hospital National Poll on Children's Health at Michigan Medicine.

"Regular preventive dental care helps keep children's teeth healthy and allows providers to address any tooth decay ...

We find routes to destination and remember special places because there is an area somewhere in the brain that functions like a GPS and navigation system. When taking a new path for the first time, we pay attention to the landmarks along the way. Owing to such navigation system, it becomes easier to find destinations along the path after having already used the path. Over the years, scientists have learned, based on a variety of animal experiments, that cells in the brain region called hippocampus are responsible for spatial perception and are activated in discrete positions ...

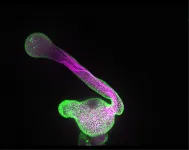

Lipids are the building blocks of a cell's envelope - the cell membrane. In addition to their structural function, some lipids also play a regulatory role and decisively influence cell growth. This has been investigated in a new study by scientists at Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg (MLU). The impact of the lipids depends on how they are distributed over the plasma membrane. The study was published in "The Plant Cell".

If plant cells want to move, they need to grow. One notable example of this is the pollen tube. When pollen lands on a flower, the pollen tube grows directionally into the female reproductive organs. This allows the male gametes to be delivered, so fertilisation can occur. The pollen tube is special ...

An international team of scientists has sequenced the genome of a capuchin monkey for the first time, uncovering new genetic clues about the evolution of their long lifespan and large brains.

Published in PNAS, the work was led by the University of Calgary in Canada and involved researchers at the University of Liverpool.

"Capuchins have the largest relative brain size of any monkey and can live past the age of 50, despite their small size, but their genetic underpinnings had remained unexplored until now," explains Professor Joao Pedro De Magalhaes, who researches ageing at the University of Liverpool.

The researchers developed and annotated a reference assembly for white-faced ...

Aspirin should be favoured over warfarin to prevent blood clotting in children who undergo a surgery that replumbs their hearts, according to a new study.

The research, led by the Murdoch Children's Research Institute (MCRI) and published in The Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery, will have implications for clinicians when prescribing blood thinning medications after Fontan surgery, a complex congenital heart disease operation redirecting blood flow from the lower body to the lungs.

The Fontan procedure is offered to children born with severe heart defects, allowing the child to live with just one pumping heart chamber ...