(Press-News.org) PITTSBURGH, Feb. 15, 2021 - Why do patients who receive antipsychotic medications to manage schizophrenia and bipolar disorder quickly gain weight and develop prediabetes and hyperinsulemia? The question remained a mystery for decades, but in a paper published today in Translational Psychiatry, researchers from the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine finally cracked the enigma.

Antipsychotic drugs, scientists showed, not only block dopamine signaling in the brain but also in the pancreas, leading to uncontrolled production of blood glucose-regulating hormones and, eventually, obesity and diabetes.

"There are dopamine theories of schizophrenia, drug addiction, depression and neurodegenerative disorders, and we are presenting a dopamine theory of metabolism," said lead author Despoina Aslanoglou, Ph.D., a postdoctoral fellow at Pitt's Department of Psychiatry. "We're seeing now that it is not only interesting to study dopamine in the brain, but it is equally interesting and important to study it in the periphery."

Dopamine is a neurotransmitter that acts as a chemical messenger between neurons and is commonly known to play a role in pleasure, motivation and learning. And antipsychotic medications--such as clozapine, olanzapine and haloperidol--relieve hallucinations and delirium by blocking a subtype of dopaminergic receptors in the brain called D2-like receptors and preventing dopamine molecules from causing neurological effects.

But, as Aslanoglou and senior author Zachary Freyberg, M.D., Ph.D., assistant professor of psychiatry and cell biology at Pitt, found, it's not so simple.

"We still don't really understand how dopamine signals biologically," said Freyberg. "Even decades after dopamine receptors have been discovered and cloned, we still deploy this 'magical thinking' approach: something happens that's good enough. We use drugs that work on dopamine receptors, but how they intersect with this 'magical system' is even less understood."

The human pancreas contains miniature structures called pancreatic islets, which are made up of alpha and beta cells whose function is to produce and secrete hormones that regulate blood glucose. Alpha cells produce glucagon to raise blood glucose, and beta cells produce insulin to lower blood glucose back to normal.

If even one player in the glucose-regulating machinery breaks, our bodies begin to suffer. Low blood glucose makes us feel dizzy and faint, while high blood glucose--when sustained for a long time--causes diabetes and other complications in the cardiovascular system.

And, as it turns out, dopamine can tip the scales.

Freyberg's team found that both pancreatic alpha and beta cells can make their own dopamine, confirming that its effects aren't limited to the brain. What's more, while beta cells primarily rely on the uptake of the dopamine precursor L-DOPA, alpha cells can make L-DOPA from scratch and ramp up its production in response to glucose. This raises the possibility that alpha cells can use dopamine to not only signal at their own receptors, but also supply it to beta cells, where it acts on D2-like receptors and inhibits secretion of glucose-lowering insulin.

And unexpectedly, the researchers discovered that pancreatic dopamine also can act on receptors designed to recognize other molecules, such as "fight-or-flight" messengers adrenaline and noradrenaline.

At a low concentration, scientists showed, dopamine primarily binds to inhibitory D2-like dopamine receptors and blocks insulin or glucagon release. At high concentrations, however, dopamine also can bind to beta-adrenergic receptors and become stimulatory, pushing hyperglycemic effects of glucagon release in alpha cells while at the same time inhibiting insulin release in beta cells through inhibitory alpha-adrenergic receptors.

Together, these findings finally explain how psychiatric patients develop metabolic syndrome after getting treatment. Blocking inhibitory dopamine receptors with antipsychotics causes a vicious circle--the brake comes off and insulin and glucagon release become unchecked, quickly desensitizing the body and further propagating hyperinsulimia, hyperglycemia and, eventually, obesity and diabetes.

"When you identify something so important, you have to make sure you find an application for it and improve people's lives," said Aslanoglou. "Our discovery can inform us of how to better formulate drugs to target dopamine signaling. This might be a novel pathway to therapeutics in both psychiatry and metabolism."

INFORMATION:

Additional authors of the paper include Suzanne Bertera, Ph.D., Massimo Trucco, M.D., and Rita Bottino, Ph.D., all of the Allegheny Health Network Research Institute; Marta Sánchez-Soto, Ph.D., Benjamin Free, Ph.D., and David Sibley, Ph.D., all of the National Institutes of Health (NIH); Jeongkyung Lee, Ph.D., Wei Zong, Ph.D., Xiangning Xue, Ph.D., and Vijay K. Yechoor, M.D., all of Pitt; Shristi Shrestha, Ph.D., and Marcela Brissova, Ph.D., both of the Vanderbilt University Medical Center; Ryan Logan, Ph.D., of The Jackson Laboratory; and Claes B. Wollheim, M.D., of the University of Geneva, Switzerland.

This research was supported by the Department of Defense (grant # PR141292), the John F. and Nancy A. Emmerling Fund of The Pittsburgh Foundation, the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke in the NIH (grant # R01DK097160), and U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs grant VA-ORD-BLR&D I01BX002678.

To read this release online or share it, visit http://www.upmc.com/media/news/021521-Freyberg-Aslanoglou [when embargo lifts].

About the University of Pittsburgh Schools of the Health Sciences

The University of Pittsburgh Schools of the Health Sciences include the schools of Medicine, Nursing, Dental Medicine, Pharmacy, Health and Rehabilitation Sciences and the Graduate School of Public Health. The schools serve as the academic partner to the UPMC (University of Pittsburgh Medical Center). Together, their combined mission is to train tomorrow's health care specialists and biomedical scientists, engage in groundbreaking research that will advance understanding of the causes and treatments of disease and participate in the delivery of outstanding patient care. Since 1998, Pitt and its affiliated university faculty have ranked among the top 10 educational institutions in grant support from the National Institutes of Health. For additional information about the Schools of the Health Sciences, please visit http://www.health.pitt.edu .

http://www.upmc.com/media

Contact: Anastasia Gorelova

Mobile: 412-491-9411

E-mail: GorelovaA@upmc.edu

Contact: Ashley Trentrock

Mobile: 412-529-9092

E-mail: TrentrockAR@upmc.edu

For more than a decade, governments in countries across the world have made significant progress to expand their protected areas network to conserve the planet's biodiversity. According to a new study published in the journal Global Change Biology, the locations of these protected areas do not take into account the potential long-term effects of climate change in these protected areas.

Creating and managing protected areas, such as national parks, is key for biodiversity conservation. As the climate changes, however, species will disperse in order to maintain their specific habitat needs. Species that were in protected areas ...

Almost half the patients admitted to an intensive care unit (ICU) require invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV), a medical procedure that guarantees a sufficient supply of oxygen to their organs and tissues. The therapy involves connecting patients to a machine that substitutes their spontaneous breathing. In recent months it has been in general use in intensive-care patients affected by COVID-19.

Although it can often save a patient's life, invasive mechanical ventilation is not risk-free: there can be accidental injury during intubation or extubation or the muscles ...

A NEW study from the University of Chichester has shed light on how people coped psychologically with the sudden and life-changing disruption caused by COVID-19.

This new publication, by Chichester's Professor Laura Ritchie and PhD candidate Benjamin Sharpe, in collaboration with Professor Daniel Cervone of the University of Illinois at Chicago, provides a unique snapshot into people's understanding of their goals and self-beliefs amidst a shared, unexpected alteration of the daily landscape during lockdown.

Ritchie and colleagues collected their ...

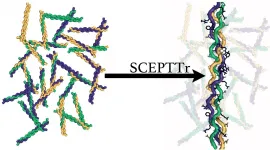

HOUSTON - (Feb. 15, 2021) - Collagen is the king of biological proteins, and now it has a SCEPTTr.

That's the handle of an algorithm developed by Rice University scientists who study natural and synthetic versions of collagen, which accounts for about a third of the body's proteins and forms the fibrous glue in skin, bones, muscles, tendons and ligaments.

The program -- full name, Scoring function for Collagen-Emulating-Peptides' Temperature of Transition -- accurately predicts the stability of collagen triple helices, the primary structure that forms fibrils.

The Rice team led by chemist and bioengineer Jeffrey ...

According to some estimates, chronic pain affects up to 40% of Americans, and treating it frustrates both clinicians and patients--a frustration that's often compounded by a hesitation to prescribe opioids for pain.

A new study from the University of Michigan School of Dentistry confirms that a low dose of a drug called naltrexone is a good option for patients with orofacial and chronic pain, without the risk of addiction, said first author Elizabeth Hatfield, a clinical lecturer in the Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery and Hospital Dentistry.

Naltrexone is a semisynthetic opioid first developed in ...

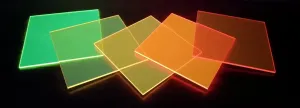

HOUSTON - (Feb. 15, 2021) - Rice University engineers have suggested a colorful solution to next-generation energy collection: Luminescent solar concentrators (LSCs) in your windows.

Led by Rafael Verduzco and postdoctoral researcher and lead author Yilin Li of Rice's Brown School of Engineering, the team designed and built foot-square "windows" that sandwich a conjugated polymer between two clear acrylic panels.

That thin middle layer is the secret sauce. It's designed to absorb light in a specific wavelength and guide it to panel edges lined with solar cells. Conjugated polymers are chemical compounds ...

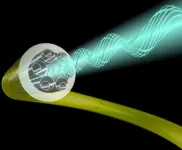

Researchers from the University of Southampton and Université Laval, Canada, have successfully measured for the first time back-reflection in cutting-edge hollow-core fibres that is around 10,000 times lower than conventional optical fibres.

This discovery, published this week in The Optical Society's flagship Optica journal, highlights yet another optical property in which hollow-core fibres are capable of outperforming standard optical fibres.

Research into improved optical fibres is key to enable progress in numerous photonic applications. Most notably, these would improve Internet performance ...

Oncotarget recently published "Polymerized human hemoglobin increases the effectiveness of cisplatin-based chemotherapy in non-small cell lung cancer" which reported that unfortunately, a significant portion of NSCLC patients relapse due to cisplatin chemoresistance.

Administration of hemoglobin-based oxygen carriers is a promising strategy to alleviate hypoxia in the tumor, which may make cisplatin more effective.

The R-state PolyHb administered in this study is unable to deliver O2 unless under severe hypoxia which significantly limits its oxygenation potential.

In vitro sensitivity studies indicate that the administration of PolyHb increases the effectiveness of cisplatin under ...

BOSTON -- While PCR testing has been used widely for COVID-19 diagnosis, it only provides information on who is currently infected. Antibody testing can tell who has been previously exposed to SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, a metric that is essential for tracking spread across a population. It may also, as a study recently published in the journal Nature Communications shows, hold the key to understanding the immune response to the virus.

Led by Galit Alter, PhD, Core Member of the Ragon Institute of MGH, MIT and Harvard, this study found that while antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 may be a good way to measure exposure to the virus, their presence alone wasn't enough to determine if a person had long-lasting protection. Instead, antibody effector functions associated ...

OAK BROOK, Ill. - Radiomics--the extraction of very detailed quantitative features from medical images--provides a refined understanding of how cocaine use and other risk factors affect the course of coronary artery disease, according to a study published in Radiology. Researchers said the study shows the power of radiomics to improve understanding of not just cardiovascular disease, but cancer and other conditions as well.

Coronary artery disease typically develops over time as plaque builds up inside the arteries. This process, known as atherosclerosis, ...