(Press-News.org) New research has found that a group of genes that reduces the risk of developing severe COVID-19 by around 20% is inherited from Neanderthals

These genes, located on chromosome 12, code for enzymes that play a vital role in helping cells destroy the genomes of invading viruses

The study suggests that enzymes produced by the Neanderthal variant of these genes are more efficient which helps protect against severe COVID-19

This genetic variant was passed to humans around 60,000 years ago via interbreeding between modern humans and Neanderthals

The genetic variant has increased in frequency over the last millennium and is now found in around half of people living outside Africa

SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, impacts people in different ways after infection. Some experience only mild or no symptoms at all while others become sick enough to require hospitalization and may develop respiratory failure and die.

Now, researchers at the Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology Graduate University (OIST) in Japan and the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Biology in Germany have found that a group of genes that reduces the risk of a person becoming seriously ill with COVID-19 by around 20% is inherited from Neanderthals.

"Of course, other factors such as advanced age or underlying conditions such as diabetes have a significant impact on how ill an infected individual may become," said Professor Svante Pääbo, who leads the Human Evolutionary Genomics Unit at OIST. "But genetic factors also play an important role and some of these have been contributed to present-day people by Neanderthals."

Last year, Professor Svante Pääbo and his colleague Professor Hugo Zeberg reported in Nature that the greatest genetic risk factor so far identified, doubling the risk to develop severe COVID-19 when infected by the virus, had been inherited from Neanderthals.

Their latest research builds on a new study, published in December last year from the Genetics of Mortality in Critical Care (GenOMICC) consortium in the UK, which collected genome sequences of 2,244 people who developed severe COVID-19. This UK study pinpointed additional genetic regions on four chromosomes that impact how individuals respond to the virus.

Now, in a study published today in PNAS, Professor Pääbo and Professor Zeberg show that one of the newly identified regions carries a variant that is almost identical to those found in three Neanderthals - a ~50,000-year-old Neanderthal from Croatia, and two Neanderthals, one around 70,000 years old and the other around 120,000 years old, from Southern Siberia.

Surprisingly, this second genetic factor influences COVID-19 outcomes in the opposite direction to the first genetic factor, providing protection rather than increasing the risk to develop severe COVID-19. The variant is located on chromosome 12 and reduces the risk that an individual will require intensive care after infection by about 22%.

"It's quite amazing that despite Neanderthals becoming extinct around 40,000 years ago, their immune system still influences us in both positive and negative ways today," said Professor Pääbo.

To try to understand how this variant affects COVID-19 outcomes, the research team took a closer look at the genes located in this region. They found that three genes in this region, called OAS, code for enzymes that are produced upon viral infection and in turn activate other enzymes that degrade viral genomes in infected cells.

"It seems that the enzymes encoded by the Neanderthal variant are more efficient, reducing the chance of severe consequences to SARS-CoV-2 infections," Professor Pääbo explained.

The researchers also studied how the newly discovered Neanderthal-like genetic variants changed in frequency after ending up in modern humans some 60,000 years ago.

To do this, they used genomic information retrieved by different research groups from thousands of human skeletons of varying ages.

They found that the variant increased in frequency after the last Ice Age and then increased in frequency again during the past millennium. As a result, today it occurs in about half of people living outside Africa and in around 30% of people in Japan. In contrast, the researchers previously found that the major risk variant inherited from Neanderthals is almost absent in Japan.

"The rise in the frequency of this protective Neanderthal variant suggests that it may have been beneficial also in the past, maybe during other disease outbreaks caused by RNA viruses," said Professor Pääbo.

INFORMATION:

Researchers from Skoltech and their colleagues have demonstrated that nanoengineered biodegradable microcapsules can guide the development of hippocampal neurons in an in vitro experiment. The microcapsules deliver nerve growth factor, a peptide necessary for neuron growth. The paper describing this work was published in the journal Pharmaceutics.

Many neurodegenerative conditions that can lead to severe disorders are associated with depleted levels of growth factors in the brain - neuropeptides that help neurons grow, proliferate and survive. Some clinical studies of Alzheimer's and Parkinson's diseases have shown that delivering these growth factors to specific degenerating neurons can have a therapeutic effect. ...

Scientists from the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) have developed a simple way to better evaluate the potential of novel materials to store or release heat on demand in your home, office, or other building in a way that more efficiently manages the building's energy use.

Their work, featured in Nature Energy, proposes a new design method that could make the process of heating and cooling buildings more manageable, less expensive, more efficient, and better prepared to flexibly manage power from renewable energy sources that do not always deliver ...

Last year, researchers at Karolinska Institutet in Sweden and the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany showed that a major genetic risk factor for severe COVID-19 is inherited from Neandertals. Now the same researchers show, in a study published in PNAS, that Neandertals also contributed a protective variant. Half of all people outside Africa carry a Neandertal gene variant that reduces the risk of needing intensive care for COVID-19 by 20 percent.

Some people become seriously ill when infected with SARS-CoV-2 while others get only mild or no symptoms. In addition to ...

How do plants build resilience? An international research team led by the University of Göttingen studied the molecular mechanisms of the plant immune system. They were able to show a connection between a relatively unknown gene and resistance to pathogens. The results of the study were published in the journal The Plant Cell.

Scientists from "PRoTECT" - Plant Responses To Eliminate Critical Threats - investigated the molecular mechanisms of the immune system of a small flowering plant known as thale cress (Arabidopsis thaliana). PRoTECT ...

The ongoing health disaster of the past 12 months has exposed the crises facing nursing homes in Canada and the United States and the struggles of the staff working in them.

Writing in the Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis: Research and Practice, PhD student Daniel Dickson, his supervisor Patrik Marier, professor of political science, and co-author Robert Henry Cox of the University of South Carolina perform a comparative analysis of those workers' experiences. In it, they look at Quebec (including those at government-run CHSLDs), British Columbia, Washington State and Ohio ...

Hamilton, ON (February 16, 2021) - A McMaster stem cell research team has made an important early step in developing a new class of therapeutics for patients with a deadly blood cancer.

The team has discovered that for acute myeloid leukemia (AML) patients, there is a dopamine receptor pathway that becomes abnormally activated in the cancer stem cells. This inspired the clinical investigation of a dopamine receptor-inhibiting drug thioridazine as a new therapy for patients, and their focus on adult AML has revealed encouraging results.

AML is a particularly deadly cancer that starts with a DNA mutation in the blood stem cells of the bone marrow that produce too many infection-fighting white blood cells. According ...

The ongoing fight of science against cancer has made great strides, but cancer cells have not made it easy. The complexity of cancer cells and their adaptive evolutionary nature complicate the search for effective cures. Multiple DNA repair pathways in healthy cells typically work to rectify DNA damages caused by sources within the organism, like spontaneous DNA mutations, or from outside, like ultraviolet radiation.

But what happens when these pathways malfunction? It is known that deficiencies in these pathways increase the instability of the genes, and this causes cancer to develop. Therefore, detailed knowledge of how DNA repair pathways participate in this process is crucial for tracking tumor progression, understanding the emergence of drug ...

Melanoma is by far the deadliest form of skin cancer, killing more than 7,000 people in the United States in 2019 alone. Early detection of the disease dramatically reduces the risk of death and the costs of treatment, but widespread melanoma screening is not currently feasible. There are about 12,000 practicing dermatologists in the US, and they would each need to see 27,416 patients per year to screen the entire population for suspicious pigmented lesions (SPLs) that can indicate cancer.

Computer-aided diagnosis (CAD) systems have been developed in recent years to try to solve this problem by analyzing images of ...

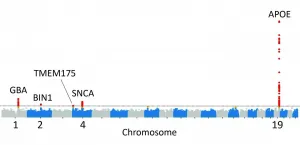

In a study led by National Institutes of Health (NIH) researchers, scientists found that five genes may play a critical role in determining whether a person will suffer from Lewy body dementia, a devastating disorder that riddles the brain with clumps of abnormal protein deposits called Lewy bodies. Lewy bodies are also a hallmark of Parkinson's disease. The results, published in Nature Genetics, not only supported the disease's ties to Parkinson's disease but also suggested that people who have Lewy body dementia may share similar genetic profiles to those who have Alzheimer's disease.

"Lewy body dementia is a devastating brain disorder for which we have no effective treatments. Patients often appear to suffer the worst of both Alzheimer's ...

Reston, VA--Molecular imaging can successfully predict response to a novel treatment for ER-positive, HER2-negative metastatic breast cancer patients who are resistant to hormonal therapy. According to research published in the February issue of the Journal of Nuclear Medicine, positron emission tomography (PET) imaging using an imaging agent called 18F-fluoroestradiol can help to determine which patients could benefit from treatments that could spare them from unnecessary chemotherapy.

Nearly two-thirds of invasive breast cancers are ER-positive, and endocrine therapy is the mainstay of treatment for these tumors because of its favorable toxicity profile and efficacy. Should cancer progress in these patients, however, salvage endocrine therapy with molecularly targeted agents ...