(Press-News.org) Nearly a half-million people a year die from sudden cardiac death (SCD) in the U.S. -- the result of malfunctions in the heart's electrical system.

A leading cause of SCD in young athletes is arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy (ACM), a genetic disease in which healthy heart muscle is replaced over time by scar tissue (fibrosis) and fat.

Stephen Chelko, an assistant professor of biomedical sciences at the Florida State University College of Medicine, has developed a better understanding of the pathological characteristics behind the disease, as well as promising avenues for prevention. His findings are published in the current issue of Science Translational Medicine.

Individuals with ACM possess a mutation causing arrhythmias, which ordinarily are non-fatal if managed and treated properly. However, Chelko shows that exercise not only amplifies those arrhythmias, but causes extensive cell death. Their only option is to avoid taking part in what should be a healthy and worthwhile endeavor: exercise.

"There is some awful irony in that exercise, a known health benefit for the heart, leads to cell death in ACM subjects," Chelko said. "Now, we know that endurance exercise, in particular, leads to large-scale myocyte cell death due to mitochondrial dysfunction in those who suffer from this inherited heart disease."

Several thousand mitochondria are in nearly every cell in the body, processing oxygen and converting food into energy. Considered the powerhouse of all cells (they produce 90 percent of the energy our bodies need to function properly), they also play another important role as a protective antioxidant.

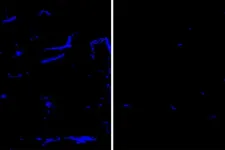

As mitochondria fail to function properly, and myocyte cells in the heart die, healthy muscles are replaced by scar tissue and fatty cells. Eventually, the heart's normal electrical signals are reduced to an erratic and disorganized firing of impulses from the lower chambers, leading to an inability to properly pump blood during heavy exercise. Without immediate medical treatment, death occurs within minutes.

Chelko's research gets to the heart of the process involved in mitochondrial dysfunction.

"Ultimately, mitochondria become overwhelmed and expel 'death signals' that are sent to the nucleus, initiating large-scale DNA fragmentation and cell death," Chelko said. "This novel study unravels a pathogenic role for exercise-induced, mitochondrial-mediated cell death in ACM hearts."

In addition to providing a better understanding of the process involved, Chelko discovered that cell death can be prevented by inhibiting two different mitochondrial proteins. One such approach utilizes a novel targeting peptide developed for Chelko's research by the National Research Council in Padova, Italy.

That discovery opens avenues for the development of new therapeutic options to prevent myocyte cell death, cardiac dysfunction and the pathological progression leading to deadly consequences for people living with ACM.

INFORMATION:

This research was funded by an American Heart Association Career Development Award.

The trial found that using sensor-based asthma inhalers may improve control of the condition and improve the quality of life for caregivers.

Greatest gains were among non-Hispanic Black participants, who experience more frequent and severe asthma than other groups.

Based on the study results, this asthma intervention should be considered for use by primary care, allergy and pulmonary care providers, to help engage diverse populations of pediatric asthma patients and their caregivers.

CHICAGO (February 17, 2021) -- Sensor-based inhalers integrated into health care providers' clinical workflows may help improve medication adherence and support children with asthma - and their families - to more effectively manage this condition, according ...

Numerous studies have shown that trained dogs can detect many kinds of disease -- including lung, breast, ovarian, bladder, and prostate cancers, and possibly Covid-19 -- simply through smell. In some cases, involving prostate cancer for example, the dogs had a 99 percent success rate in detecting the disease by sniffing patients' urine samples.

But it takes time to train such dogs, and their availability and time is limited. Scientists have been hunting for ways of automating the amazing olfactory capabilities of the canine nose and brain, in a compact device. Now, a team of researchers at MIT and other institutions has come up with a system that can detect the chemical and microbial content of an air sample with ...

As people age, a normal brain protein known as amyloid beta often starts to collect into harmful amyloid plaques in the brain. Such plaques can be the first step on the path to Alzheimer's dementia. When they form around blood vessels in the brain, a condition known as cerebral amyloid angiopathy, the plaques also raise the risk of strokes.

Several antibodies that target amyloid plaques have been studied as experimental treatments for Alzheimer's disease. Such antibodies also may have the potential to treat cerebral amyloid angiopathy, although they haven't yet been evaluated in clinical trials. ...

An international team led by researchers at the Centre for Palaeogenetics in Stockholm has sequenced DNA recovered from mammoth remains that are up to 1.2 million years old. The analyses show that the Columbian mammoth that inhabited North America during the last ice age was a hybrid between the woolly mammoth and a previously unknown genetic lineage of mammoth. In addition, the study provides new insights into when and how fast mammoths became adapted to cold climate. These findings are published today in Nature.

Around one million years ago there were no woolly or Columbian mammoths, as they had not yet evolved. This was the time of their predecessor, the ...

DURHAM, N.C. -- A new pair of studies from a Duke research team's long-term work in New Zealand make the case that mental health struggles in early life can lead to poorer physical health and advanced aging in adulthood.

But because mental health problems peak early in life and can be identified, the researchers say that more investment in prompt mental health care could be used to prevent later diseases and lower societal healthcare costs.

"The same people who experience psychiatric conditions when they are young go on to experience excess age-related physical diseases and neurodegenerative diseases when they are older adults," explained Terrie Moffitt, the Nannerl O. Keohane professor ...

A University of Sydney-led international team of scientists has revealed the shape of one of the most important molecular machines in our cellsthe glutamate transporter, helping to explain how our brain cells communicate with one another.

Glutamate transporters are tiny proteins on the surface of all our cells that shut on and off the chemical signals that have a big role in making sure all cell-to-cell talk runs smoothly. They are also involved in nerve signalling, metabolism and learning and memory.

The researchers captured the transporters in exquisite detail using cryogenic electron microscopy (cryo-EM), showing they look like a 'twisted elevator' embedded in the cell membrane.

This world-first discovery ...

Almost one in five people lacks the protein α-actinin-3 in their muscle fibre. Researchers at Karolinska Institutet in Sweden now show that more of the skeletal muscle of these individuals comprises slow-twitch muscle fibres, which are more durable and energy-efficient and provide better tolerance to low temperatures than fast-twitch muscle fibres. The results are published in the scientific journal The American Journal of Human Genetics.

Skeletal muscle comprises fast-twitch (white) fibres that fatigue quickly and slow-twitch (red) fibres that are more resistant to fatigue. The protein α-actinin-3, which is found only ...

Robotic dogs, laughter therapy and mindfulness are some of the ways that might help people - particularly the elderly - cope with loneliness and social isolation while social distancing, say researchers at the University of Cambridge.

A team at Cambridge's School of Medicine carried out a systematic review looking at the existing evidence on different approaches to tackling loneliness and social isolation. While all the individual studies were carried out pre-pandemic, the team considered which approaches might be feasible when people are still required to socially distance. Their results are published today in PLOS ONE.

At the start of the pandemic in the UK, over 1.5 million people were told they must self-isolate ...

Lakes underneath the Antarctic ice sheet could be more hospitable than previously thought, allowing them to host more microbial life.

This is the finding of a new study that could help researchers determine the best spots to search for microbes that could be unique to the region, having been isolated and evolving alone for millions of years. The work could even provide insights into similar lakes beneath the surfaces of icy moons orbiting Jupiter and Saturn, and the southern ice cap on Mars.

Lakes can form beneath the thick ice sheet of Antarctica where the weight of ice causes immense pressure at the base, lowering the melting point of ice. This, coupled with gentle heating from rocks below and the insulation provided by the ice from the cold air above, allows pools of liquid water ...

WASHINGTON --- Recent data reveals that gay men living with HIV report having supportive relationships with family, friends, or in informal relationships rather than with primary romantic partners, while gay men who are HIV negative report having relationships mainly with primary partners. Additionally, gay men living with HIV were more likely to report no primary or secondary supportive partnerships compared to men who are HIV negative. The analysis was led by researchers at Georgetown University Medical Center.

Along with successful HIV treatments, it is known that the presence of social support impacts long-term survival among men living with HIV. However, little has been known about the types of ...