(Press-News.org) As people age, a normal brain protein known as amyloid beta often starts to collect into harmful amyloid plaques in the brain. Such plaques can be the first step on the path to Alzheimer's dementia. When they form around blood vessels in the brain, a condition known as cerebral amyloid angiopathy, the plaques also raise the risk of strokes.

Several antibodies that target amyloid plaques have been studied as experimental treatments for Alzheimer's disease. Such antibodies also may have the potential to treat cerebral amyloid angiopathy, although they haven't yet been evaluated in clinical trials. But all of the anti-amyloid antibodies that have successfully reduced amyloid plaques in Alzheimer's clinical trials also can cause a worrisome side effect: an increased risk of brain swelling and bleeds.

Now, researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis have identified an antibody that, in mice, removes amyloid plaques from brain tissue and blood vessels without increasing risk of brain bleeds. The antibody targets a minor component of amyloid plaques known as apolipoprotein E (APOE).

The findings, published Feb. 17 in Science Translational Medicine, suggest a potentially safer approach to removing harmful amyloid plaques as a way of treating Alzheimer's disease and cerebral amyloid angiopathy.

"Alzheimer's researchers have been searching for decades for therapies that reduce amyloid in the brain, and now that we have some promising candidates, we find that there's this complication," said senior author David Holtzman, MD, the Andrew B. and Gretchen P. Jones Professor and head of the Department of Neurology. "Each of the antibodies that removes amyloid plaques in clinical trials is a little different, but they all have this problem, to a greater or lesser degree. We've taken a different approach by targeting APOE, and it seems to be effective at removing amyloid from both the brain tissue and the blood vessels, while avoiding this potentially dangerous side effect."

The side effect, called ARIA, for amyloid-related imaging abnormalities, is visible on brain scans. Such abnormalities indicate swelling or bleeding in the brain caused by inflammation, and can lead to headaches, confusion and even seizures. In clinical trials for anti-amyloid antibodies, roughly 20% of participants develop ARIA, although not all have symptoms.

Anti-amyloid antibodies work by alerting the immune system to the presence of unwanted material -- amyloid plaques -- and directing the cleanup crew -- inflammatory cells known as microglia -- to clear out such debris. ARIA seems to be the result of an overenthusiastic inflammatory response. Holtzman and first author Monica Xiong, a graduate student, suspected that an antibody that targets only a minor part of the amyloid plaque might elicit a more restrained response that clears the plaques from both brain tissue and blood vessels without causing ARIA.

Fortunately, they had one such antibody on hand: an antibody called HAE-4 that targets a specific form of human APOE that is found sparsely in amyloid plaques and triggers the removal of plaques from brain tissue. To determine whether HAE-4 also removes amyloid from brain blood vessels, the researchers used mice genetically modified with human genes for amyloid and APOE4, a form of APOE associated with a high risk of developing Alzheimer's and cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Such mice develop abundant amyloid plaques in brain tissue and brain blood vessels by the time they are about six months old. Along with Holtzman and Xiong, the research team included co-authors Hong Jiang, PhD, a senior scientist in Holtzman's lab, and Gregory J. Zipfel, MD, the Ralph G. Dacey Distinguished Professor of Neurological Surgery and head of the Department of Neurosurgery, among others.

Experiments showed that eight weeks of treating mice with HAE-4 reduced amyloid plaques in brain tissue and brain blood vessels. Treatment also significantly improved the ability of brain blood vessels to dilate and constrict on demand, an important sign of vascular health.

Amyloid plaques in brain blood vessels are dangerous because they can lead to blockages or ruptures that cause strokes. The researchers compared the number of brain bleeds in mice treated for eight weeks with either HAE-4 or aducanumab, an anti-amyloid antibody that is in phase 3 clinical trials for Alzheimer's. The mice had a baseline level of tiny brain bleeds because of their genetic predisposition for amyloid buildup in blood vessels. But aducanumab significantly increased the number of bleeds while HAE-4 did not.

Further investigation revealed that HAE-4 and aducanumab initially elicited immune responses against amyloid plaques that were similar in strength. But mice treated with the anti-APOE antibody resolved the inflammation within two months, while inflammation persisted in mice treated with the anti-amyloid antibody.

"Some people get cerebral amyloid angiopathy and never get Alzheimer's dementia, but they may have strokes instead," Holtzman said. "A buildup of amyloid in brain blood vessels can be managed by controlling blood pressure and other things, but there isn't a specific treatment for it. This study is exciting because it not only shows that we can treat the condition in an animal model, but we may be able to do it without the side effects that undermine the effectiveness of other anti-amyloid therapeutics."

INFORMATION:

An international team led by researchers at the Centre for Palaeogenetics in Stockholm has sequenced DNA recovered from mammoth remains that are up to 1.2 million years old. The analyses show that the Columbian mammoth that inhabited North America during the last ice age was a hybrid between the woolly mammoth and a previously unknown genetic lineage of mammoth. In addition, the study provides new insights into when and how fast mammoths became adapted to cold climate. These findings are published today in Nature.

Around one million years ago there were no woolly or Columbian mammoths, as they had not yet evolved. This was the time of their predecessor, the ...

DURHAM, N.C. -- A new pair of studies from a Duke research team's long-term work in New Zealand make the case that mental health struggles in early life can lead to poorer physical health and advanced aging in adulthood.

But because mental health problems peak early in life and can be identified, the researchers say that more investment in prompt mental health care could be used to prevent later diseases and lower societal healthcare costs.

"The same people who experience psychiatric conditions when they are young go on to experience excess age-related physical diseases and neurodegenerative diseases when they are older adults," explained Terrie Moffitt, the Nannerl O. Keohane professor ...

A University of Sydney-led international team of scientists has revealed the shape of one of the most important molecular machines in our cellsthe glutamate transporter, helping to explain how our brain cells communicate with one another.

Glutamate transporters are tiny proteins on the surface of all our cells that shut on and off the chemical signals that have a big role in making sure all cell-to-cell talk runs smoothly. They are also involved in nerve signalling, metabolism and learning and memory.

The researchers captured the transporters in exquisite detail using cryogenic electron microscopy (cryo-EM), showing they look like a 'twisted elevator' embedded in the cell membrane.

This world-first discovery ...

Almost one in five people lacks the protein α-actinin-3 in their muscle fibre. Researchers at Karolinska Institutet in Sweden now show that more of the skeletal muscle of these individuals comprises slow-twitch muscle fibres, which are more durable and energy-efficient and provide better tolerance to low temperatures than fast-twitch muscle fibres. The results are published in the scientific journal The American Journal of Human Genetics.

Skeletal muscle comprises fast-twitch (white) fibres that fatigue quickly and slow-twitch (red) fibres that are more resistant to fatigue. The protein α-actinin-3, which is found only ...

Robotic dogs, laughter therapy and mindfulness are some of the ways that might help people - particularly the elderly - cope with loneliness and social isolation while social distancing, say researchers at the University of Cambridge.

A team at Cambridge's School of Medicine carried out a systematic review looking at the existing evidence on different approaches to tackling loneliness and social isolation. While all the individual studies were carried out pre-pandemic, the team considered which approaches might be feasible when people are still required to socially distance. Their results are published today in PLOS ONE.

At the start of the pandemic in the UK, over 1.5 million people were told they must self-isolate ...

Lakes underneath the Antarctic ice sheet could be more hospitable than previously thought, allowing them to host more microbial life.

This is the finding of a new study that could help researchers determine the best spots to search for microbes that could be unique to the region, having been isolated and evolving alone for millions of years. The work could even provide insights into similar lakes beneath the surfaces of icy moons orbiting Jupiter and Saturn, and the southern ice cap on Mars.

Lakes can form beneath the thick ice sheet of Antarctica where the weight of ice causes immense pressure at the base, lowering the melting point of ice. This, coupled with gentle heating from rocks below and the insulation provided by the ice from the cold air above, allows pools of liquid water ...

WASHINGTON --- Recent data reveals that gay men living with HIV report having supportive relationships with family, friends, or in informal relationships rather than with primary romantic partners, while gay men who are HIV negative report having relationships mainly with primary partners. Additionally, gay men living with HIV were more likely to report no primary or secondary supportive partnerships compared to men who are HIV negative. The analysis was led by researchers at Georgetown University Medical Center.

Along with successful HIV treatments, it is known that the presence of social support impacts long-term survival among men living with HIV. However, little has been known about the types of ...

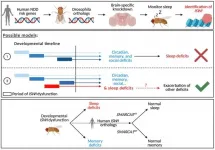

PHILADELPHIA - The mutation of a gene that has been associated with neurodevelopmental disorders like autism spectrum disorder led to marked sleep disturbances in fruit flies, according to a new study from scientists in the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania. The findings, published Wednesday in Science Advances, provide further evidence that sleep is linked to early neurodevelopmental processes and could guide future treatments for patients.

While sleep disruption is a commonly reported symptom across neurodevelopmental disorders, including autism, it is often treated clinically as a "secondary effect" ...

In ancient European settlements, livestock use was likely primarily determined by political structure and market demands, according to a study published February 17, 2021 in the open-access journal PLOS ONE by Ariadna Nieto-Espinet and colleagues of the Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas, Barcelona.

Zooarchaeology - the study of animal remains from archaeological sites - has great potential to provide information on past human communities. Livestock preferences are known to have changed over time in Europe, but little is known about how much these changes are influenced by environmental, economic, or political conditions of ancient settlements.

In ...

The new method works without extremely high temperatures, is therefore more energy-efficient and has a significantly higher recovery rate (approx. 96 per cent of the starting material) than established processes. These findings will be published on 17 February 2021 in the scientific journal Nature.

Mechanical recycling vs. chemical recycling

"The direct re-utilization of plastics is often hampered by the fact that, in practice, mechanical recycling only functions to a limited degree - because the plastics are contaminated and mixed with additives, which impairs the properties ...