(Press-News.org) Cancer researcher Rita Fior uses zebrafish to study human cancer. Though this may seem like an unlikely match, her work shows great promise with forthcoming applications in personalised medicine.

The basic principle of Fior's approach relies on transplanting human cancer cells into dozens of zebrafish larvae. The fish then serve as "living test tubes" where various treatments, such as different chemotherapy drugs, can be tested to reveal which works best. The assay is rapid, producing an answer within four short days.

Some years ago, when Fior was developing this assay, she noticed something curious. "The majority of human tumour cells successfully engrafted in the fish, but some tumours didn't. They would just disappear within a day or two. However, when I treated the transplanted fish with chemotherapy, these tumors would not disappear anymore. They engrafted much more", she recalls.

This seemingly paradoxical observation triggered a new working hypothesis. "Chemotherapy suppresses the immune system", Fior explains. "If the tumour is rejected under normal conditions, but thrives in immuno-suppressed animals, then this points towards a new explanation: the fish's immune system is actively destroying the cancer cells. Whereas in the ones that implant well, the tumor is able to suppress the fish's immune system."

Soon after, Fior, together with Vanda Povoa, a doctoral student in her lab at the Champalimaud Centre for the Unknown in Portugal, set off on a new research project. It's main conclusions, published today (February 19th) in the journal Nature Communications, advance our understanding of how cancer-immune interactions may lead to immunotherapy resistance and tumour growth. In the long run, these results may contribute to the development of new treatments and diagnostics.

Good Cop

Following this serendipitous observation, the researchers began systematically investigating why certain tumours are eliminated while others survive.

They focused on a pair of human colorectal cancer cells that were derived from the same patient but showed these contrasting behaviours. One was derived from the primary tumor and was constantly rejected from the fish; whereas the other was derived from a lymph node metastasis but implanted very efficiently.

They started by characterising the immune cells that were summoned to the tumor site. Specifically, they zoomed-in on cells of a subsystem called innate immunity.

"Contrary to mature zebrafish, the larvae only have innate immunity, which is the body's first line of defence. This offers a vantage point to study the role of innate immune cells in cancer, which is not very well understood", Fior explains.

The team proceeded to quantify the number and type of innate immune cells in the tumor microenvironment. The primary tumor [which gets rejected] was swarming with innate immune cells. But in contrast, the metastatic tumor that implants well, showed very sparse numbers of innate immune cells.

This result indicated that the researchers' hunch was correct. But to be sure, they had to artificially reduce the number of innate immune cells in the fish using selective genetic and chemical approaches. As expected, this manipulation "saved" the cells from being rejected.

Together, these results show a clear role for the innate immune system in eliminating tumour cells. But then, if the immune system is so good at getting rid of "fresh" cancer cells from the primary tumour, why would metastasis happen?

Bad Cop

"The reason is that the relationship between cancer and the immune system is far from static", says Fior. "At the beginning, cancer cells may simply try to hide from the immune system. But with time, they learn how to confuse and finally corrupt immune cells. This evolution happens through a dynamic process called 'Immunoediting'. If the process is successful, the corrupted cells begin supporting the tumour in many ways, including sending away other immune cells that could vanquish the tumour."

Is the innate immune system per se able to do cancer immunoediting? "Our results show that yes, it does indeed. This is the second study, to our knowledge, that shows this phenomenon", adds Povoa.

The researchers observed that tumor cells not only recruit different numbers of innate immune cells but can also change their function. Instead of fighting the tumour, macrophages began supporting and protecting it. Alarmingly, the researchers demonstrated that this transformation happens very quickly.

"Even though most cells from the primary tumour are rejected within a day or two, some survive. When we transplanted this small group of survivors back into the fish, we discovered that they had already acquired immune-editing capabilities! In fact, they engrafted almost as well as cells from metastatic tumours", Povoa points out.

The researchers also compared the genetic profile of metastatic and primary tumour cells and identified several interesting features. "We now have a list of candidate genes and molecules that we plan to study. We hope that by pinpointing the mechanism by which cancer cells suppress and corrupt the innate immune system we will be able to find ways of blocking this process", Fior adds.

Giving immunotherapy a boost

Fueled by this exciting set of results, Fior and Povoa are full of plans for the future. "There are so many things we can do", says Fior. "For instance, we now know that our zebrafish assay can tell if the tumour environment is immunosuppressive in just a few days. Immunotherapy is less likely to be effective in these cases. Therefore, our assay may become useful to help determine which patients will benefit mostly from immunotherapy ."

Another angle the team is thinking about is the development of new immunotherapy approaches. "The majority of immunotherapy drugs do not rely on innate immunity. They boost other immune subsystems. But as we saw, innate immunity has a great capacity for fighting cancer. Therefore, identifying the mechanisms that amplify this effect will allow us to devise new potential therapies, which could be combined with existing ones to increase their efficacy.", she concludes.

INFORMATION:

University of Warwick scientists model movements of nearly 300 protein structures in Covid-19

Scientists can use the simulations to identify potential targets to test with existing drugs, and even check effectiveness with future Covid variants

Simulation of virus spike protein, part of the virus's 'corona', shows promising mechanism that could potentially be blocked

Researchers have publicly released data on all protein structures to aid efforts to find potential drug targets: https://warwick.ac.uk/flex-covid19-data

Researchers have detailed a mechanism in the ...

Genetic mutations which occur naturally during the earliest stages of an embryo's development can cause the severe birth defect spina bifida, finds a new experimental study in mice led by UCL scientists.

The research, published in Nature Communications, explains for the first time how a 'mosaic mutation' - a mutation which is not inherited from either parent (either via sperm or egg cell) but occurs randomly during cell divisions in the developing embryo - causes spina bifida.

Specifically the scientists, based at UCL Great Ormond Street Institute of Child Health, found that when a mutation in the gene Vangl2 (which contains information needed to create spinal cord tissue) was present in 16% of developing spinal cord cells of mouse embryos, this ...

The Biden administration is revising the social cost of carbon (SCC), a decade-old cost-benefit metric used to inform climate policy by placing a monetary value on the impact of climate change. In a newly published analysis in the journal Nature, a team of researchers lists a series of measures the administration should consider in recalculating the SCC.

"President Biden signed a Day One executive order to create an interim SCC within a month and setting up a process to produce a final, updated SCC within a year," explains Gernot Wagner, a climate economist at New York University's Department of Environmental Studies and NYU's Robert F. Wagner Graduate School of Public Service and the paper's lead author. "Our work outlines how the ...

Scientific strides in HIV treatment and prevention have reduced transmissions and HIV-related deaths significantly in the United States in the past two decades. However, despite coordinated national efforts to implement HIV services, the epidemic persists, especially in the South. It also disproportionately impacts marginalized groups, such as Black/African-American and Latinx communities, women, people who use drugs, men who have sex with men, and other sexual and gender minorities. Following the release of the HIV National Strategic Plan and marking two years since the launch of the Ending the HIV Epidemic: ...

People who are racial, sexual, and gender minorities continue to be affected by HIV at significantly higher rates than white people, a disparity also reflected in the COVID-19 pandemic.

The US HIV epidemic has shifted from coastal, urban settings to the South and rural areas.

Despite its role as the largest funder for HIV research and global AIDS programs worldwide, the USA has higher rates of new HIV infections and a more severe HIV epidemic than any other G-7 nation.

Series authors call for a unified effort to curb the HIV epidemic in the USA, including universal health ...

Researchers from California Polytechnic State University and University of Oregon published a new paper in the Journal of Marketing that examines the potential benefits for firms and consumers of pick-your-price (PYP) over pay-what-you-want (PWYW) and fixed pricing strategies.

The study, forthcoming in the Journal of Marketing, is titled "The Control-Effort Trade-Off in Participative Pricing: How Easing Pricing Decisions Enhances Purchase Outcomes" and is authored by Cindy Wang, Joshua Beck, and Hong Yuan.

Over the past few decades, marketers have experimented with pricing strategies ...

The imposition of various local and national restrictions in England during the summer and autumn of 2020 gradually reduced contacts between people, but these changes were smaller and more varied than during the lockdown in March, according to a study published in the open access journal BMC Medicine.

A team of researchers at London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine (LSHTM), UK combined data from the English participants of the UK CoMix survey and information on local and national restrictions from Gov.uk collected between August 31st and December 7th 2020. CoMix is an online survey asking individuals to record details of their direct contacts in the day prior to the survey.

The authors used the data to compare the number of contacts in different settings, such ...

Boys who regularly play video games at age 11 are less likely to develop depressive symptoms three years later, finds a new study led by a UCL researcher.

The study, published in Psychological Medicine, also found that girls who spend more time on social media appear to develop more depressive symptoms.

Taken together, the findings demonstrate how different types of screen time can positively or negatively influence young people's mental health, and may also impact boys and girls differently.

Lead author, PhD student Aaron Kandola (UCL Psychiatry) said: "Screens allow us to engage in a wide range of activities. Guidelines and recommendations about screen time should be based on our understanding of how these different ...

Peer-reviewed | Observational | People

Study based on 26.5 million Medicare records finds significant racial and ethnic disparities in uptake of seasonal flu vaccine in people living in the USA aged 65 years and older during the 2015-2016 flu season.

Inequities persist among those who were vaccinated, with racial and ethnic minority groups 26-32% less likely to receive the High Dose Vaccine, which is more effective in older people, compared with white older adults.

Authors note that while these results are from the 2015-2016 flu season, the findings ...

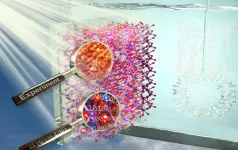

UPTON, NY--Scientists have demonstrated that modifying the topmost layer of atoms on the surface of electrodes can have a remarkable impact on the activity of solar water splitting. As they reported in Nature Energy on Feb. 18, bismuth vanadate electrodes with more bismuth on the surface (relative to vanadium) generate higher amounts of electrical current when they absorb energy from sunlight. This photocurrent drives the chemical reactions that split water into oxygen and hydrogen. The hydrogen can be stored for later use as a clean fuel. Producing only water when it recombines with oxygen to generate electricity in fuel cells, hydrogen could help us achieve a clean ...