Air pollution puts children at higher risk of disease in adulthood

2021-02-22

(Press-News.org) Children exposed to air pollution, such as wildfire smoke and car exhaust, for as little as one day may be doomed to higher rates of heart disease and other ailments in adulthood, according to a new Stanford-led study. The analysis, published in Nature Scientific Reports, is the first of its kind to investigate air pollution's effects at the single cell level and to simultaneously focus on both the cardiovascular and immune systems in children. It confirms previous research that bad air can alter gene regulation in a way that may impact long-term health - a finding that could change the way medical experts and parents think about the air children breathe, and inform clinical interventions for those exposed to chronic elevated air pollution.

"I think this is compelling enough for a pediatrician to say that we have evidence air pollution causes changes in the immune and cardiovascular system associated not only with asthma and respiratory diseases, as has been shown before," said study lead author Mary Prunicki, director of air pollution and health research at Stanford's Sean N. Parker Center for Allergy & Asthma Research. "It looks like even brief air pollution exposure can actually change the regulation and expression of children's genes and perhaps alter blood pressure, potentially laying the foundation for increased risk of disease later in life."

The researchers studied a predominantly Hispanic group of children ages 6-8 in Fresno, California, a city beset with some of the country's highest air pollution levels due to industrial agriculture and wildfires, among other sources. Using a combination of continuous daily pollutant concentrations measured at central air monitoring stations in Fresno, daily concentrations from periodic spatial sampling and meteorological and geophysical data, the study team estimated average air pollution exposures for 1 day, 1 week and 1, 3, 6 and 12 months prior to each participant visit. When combined with health and demographics questionnaires, blood pressure readings and blood samples, the data began to paint a troubling picture.

The researchers used a form of mass spectrometry to analyze immune system cells for the first time in a pollution study. The approach allowed for more sensitive measurements of up to 40 cell markers simultaneously, providing a more in-depth analysis of pollution exposure impacts than previously possible.

Among their findings: Exposure to fine particulate known as PM2.5, carbon monoxide and ozone over time is linked to increased methylation, an alteration of DNA molecules that can change their activity without changing their sequence. This change in gene expression may be passed down to future generations. The researchers also found that air pollution exposure correlates with an increase in monocytes, white blood cells that play a key role in the buildup of plaques in arteries, and could possibly predispose children to heart disease in adulthood. Future studies are needed to verify the long-term implications.

Hispanic children bear an unequal burden of health ailments, especially in California, where they are exposed to higher traffic-related pollution levels than non-Hispanic children. Among Hispanic adults, prevalence for uncontrolled hypertension is greater compared with other races and ethnicities in the U.S., making it all the more important to determine how air pollution will affect long-term health risks for Hispanic children.

Overall, respiratory diseases are killing more Americans each year, and rank as the second most common cause of deaths globally.

"This is everyone's problem," said study senior author Kari Nadeau, director of the Parker Center. "Nearly half of Americans and the vast majority of people around the world live in places with unhealthy air. Understanding and mitigating the impacts could save a lot of lives."

INFORMATION:

Nadeau is also the Naddisy Foundation Professor in Pediatric Food Allergy, Immunology, and Asthma, professor of medicine and of pediatrics and, by courtesy, of otolaryngology at the Stanford School of Medicine, and a senior fellow at the Stanford Woods Institute for the Environment. Co-authors of the study include Justin Lee, a graduate student in epidemiology and population health; Xiaoying Zhou, a research scientist at the Parker Center; Hesam Movassagh, a postdoctoral research fellow at the Parker Center during the research; Manisha Desai, a professor of biomedical informatics research and biomedical data science; and Joseph Wu, director of the Stanford Cardiovascular Institute and the Simon H. Stertzer, MD, Professor of Medicine and Radiology; and researchers from the University of Leuven; the University of California, Berkeley; the University of California, San Francisco; and Sonoma Technology.

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-02-22

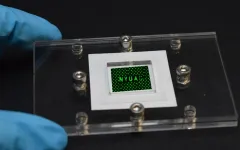

Abu Dhabi, UAE, February 22: By engineering common filter papers, similar to coffee filters, a team of NYU Abu Dhabi researchers have created high throughput arrays of miniaturized 3D tumor models to replicate key aspects of tumor physiology, which are absent in traditional drug testing platforms. With the new paper-based technology, the formed tumor models can be safely cryopreserved and stored for prolonged periods for on-demand drug testing use. These cryopreservable tumor models could provide the pharmaceutical industry with an easy and low cost method for investigating the outcomes of drug efficacy, potentially bolstering personalized ...

2021-02-22

DURHAM, N.C. - The COVID-19 pandemic has heaped additional financial strains, childcare complications and other problems on already-burdened caregivers of children diagnosed with cancer, according to a study from researchers at Duke Health and other institutions.

Surveying 360 parents and caregivers of children currently in treatment or still being monitored for cancer, the researchers found that half had to cancel or delay appointments, 77% reported increased feelings of anxiety and of those who had lost jobs or wages, 11% struggled to pay for basic needs.

The survey findings appear online this month in the journal Pediatric Blood & Cancer.

"Parents and caregivers ...

2021-02-22

HOUSTON - (Feb. 22, 2021) -Tuberculosis bacteria have evolved to remember stressful encounters and react quickly to future stress, according to a study by computational bioengineers at Rice University and infectious disease experts at Rutgers New Jersey Medical School (NJMS).

Published online in the open-access journal mSystems, the research identifies a genetic mechanism that allows the TB-causing bacterium, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, to respond to stress rapidly and in manner that is "history-dependent," said corresponding author Oleg Igoshin, a professor of bioengineering at Rice.

Researchers have long suspected that the ability of TB bacteria to remain dormant, sometimes for decades, ...

2021-02-22

COLUMBUS, Ohio - Fool the novel coronavirus once and it can't cause infection of cells, new research suggests.

Scientists have developed protein fragments - called peptides - that fit snugly into a groove on the SARS-CoV-2 Spike protein that it would normally use to access a host cell. These peptides effectively trick the virus into "shaking hands" with a replica rather than with the actual protein on a cell's surface that lets the virus in.

Previous research has determined that the novel coronavirus binds to a receptor protein on a target cell's surface called ACE2. This receptor is located on certain types of human cells in the lung and nasal cavity, providing SARS-CoV-2 many access points to infect the body.

For this work, Ohio State University scientists designed and tested peptides ...

2021-02-22

Intravenous injection of bone marrow derived stem cells (MSCs) in patients with spinal cord injuries led to significant improvement in motor functions, researchers from Yale University and Japan report Feb. 18 in the Journal of Clinical Neurology and Neurosurgery.

For more than half of the patients, substantial improvements in key functions -- such as ability to walk, or to use their hands -- were observed within weeks of stem cell injection, the researchers report. No substantial side effects were reported.

The patients had sustained, non-penetrating spinal cord injuries, in many cases from falls or minor trauma, several weeks prior to implantation of the stem cells. Their symptoms ...

2021-02-22

ITHACA, N.Y. - In the same way that Lego pieces can be arranged in new ways to build a variety of structures, genetic elements can be mixed and matched to create new genes, according to new research.

A long-proposed mechanism for creating genes, called exon shuffling, works by shuffling functional blocks of DNA sequences into new genes that express proteins.

A study, "Recurrent Evolution of Vertebrate Transcription Factors by Transposase Capture," published Feb. 19 in Science, investigates how genetic elements called transposons, or "jumping genes," are added into the mix during evolution to assemble new genes through exon shuffling.

Transposons, first discovered in the 1940s by Cornell alum and Nobel Prize-winner Barbara McClintock '23, M.A. '25, Ph.D. '27, are ...

2021-02-22

ITHACA, N.Y. - A new study identifies a mechanism that makes bacteria tolerant to penicillin and related antibiotics, findings that could lead to new therapies that boost the effectiveness of these treatments.

Antibiotic tolerance is the ability of bacteria to survive exposure to antibiotics, in contrast to antibiotic resistance, when bacteria actually grow in the presence of antibiotics. Tolerant bacteria can lead to infections that persist after treatment and may develop into resistance over time.

The study in mice, "A Multifaceted Cellular Damage Repair and Prevention Pathway Promotes ...

2021-02-22

COLUMBIA, Mo. -- When teachers encounter disruptive or noncompliant students in the classroom, they typically respond by focusing on the negative behavior. However, new research from the University of Missouri found that offering students more positive encouragement not only reduces disruptive classroom behavior, but can improve students' academic and social outcomes.

"As educators, we often focus on communicating what we don't want our students to be doing in class, but we have found that just doesn't work," said Keith Herman, a professor in the University of Missouri College of Education. "Instead, we need to be setting clear expectations ...

2021-02-22

When you slip into sleep, it's easy to imagine that your brain shuts down, but University of Michigan research suggests that groups of neurons activated during prior learning keep humming, tattooing memories into your brain.

U-M researchers have been studying how memories associated with a specific sensory event are formed and stored in mice. In a study conducted prior to the coronavirus pandemic and recently published in Nature Communications, the researchers examined how a fearful memory formed in relation to a specific visual stimulus.

They found that not only did the neurons activated by the visual ...

2021-02-22

SAN ANTONIO -- Feb. 22, 2021 -- From aboard the Juno spacecraft, a Southwest Research Institute-led instrument observing auroras serendipitously spotted a bright flash above Jupiter's clouds last spring. The Ultraviolet Spectrograph (UVS) team studied the data and determined that they had captured a bolide, an extremely bright meteoroid explosion in the gas giant's upper atmosphere.

"Jupiter undergoes a huge number of impacts per year, much more than the Earth, so impacts themselves are not rare," said SwRI's Dr. Rohini Giles, lead author of a paper outlining these findings in Geophysical Research Letters. "However, they are so short-lived that it is relatively unusual to see them. Only larger impacts can be seen from Earth, and you have to be lucky to be pointing ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Air pollution puts children at higher risk of disease in adulthood