(Press-News.org) Understanding how the immune system responds to acute brain hemorrhage could open doors to identifying treatments for this devastating disease. However, up until now, there has been limited information on inflammation in the brain from human patients, especially during the first days after a hemorrhagic stroke.

This led a team of researchers to partner with a large clinical trial of minimally-invasive surgery to tackle defining the human neuroinflammatory response in living patients.

"Our goal was to find out, for the first time, how certain key cells of the immune system are activated when they enter the brain after a hemorrhage and how this may shift over the first week. This is a critical time for our patients," said Lauren Sansing, MD, Academic Chief of Stroke and Vascular Neurology and Associate Professor of Neurology and Immunobiology at Yale.

The study, published in Science Immunology, was led by an interdisciplinary team of researchers including Sansing and Michael Askenase, PhD, Associate Research Scientist (both of Yale), and MIT scientists Alex Shalek, PhD, J. Christopher Love, PhD, and Brittany Goods, PhD. Using RNA-sequencing, they found that CD14+ macrophages and neutrophils change rapidly in the brain over the first few days after the hemorrhage. They were also able to find signatures in the macrophages that were consistent in patients with good recovery.

According to the American Heart Association, intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) makes up approximately 13% of all stroke cases. It occurs when a blood vessel bursts and releases blood into the brain, damaging the surrounding brain tissue. The mortality rate is up to 40%, most survivors are left with some disability, and there is no cure.

ICH generates an acute local immune response within and around the hematoma. Researchers have predicted that inhibiting this inflammation may improve patient outcomes, but so far haven't identified cellular and molecular targets that have been effective therapies in patients.

The study's research team partnered with the MISTIE III surgical trial, which implemented a minimally invasive surgery wherein tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) was administered via a small catheter to liquify the clot and allow drainage of blood from the brain over several days. The blood clots were shipped daily from hospitals around the nation to the Sansing Lab.

According to Dr. Askenase, "We used the detailed patient outcome measures collected by MISTIE III to identify key molecular circuits within CD14 monocytes/macrophages that correlated with good neurological outcomes, thereby uncovering potential mechanisms by which these cells may help contribute to patient recovery. In particular, we found that these cells preferentially use glycolytic metabolism to generate a key anti-inflammatory lipid known as prostaglandin E2 that, if it activates the right receptor, may have broad pro-recovery effects not only on neighboring immune cells, but also on brain-resident neurons and glia."

This could allow physicians to target the brain's immune response to ICH and unlock new treatment options for an otherwise deadly form of stroke, although further research is needed to study these pathways.

A study of this breadth demanded collaboration and coordination.

"This project could only be done with great team work across many institutions," said Dr. Sansing.

Dan Hanley, MD and the MISTIE III trial leadership, the coordination with the trial substudies through MTI:M3, the trial investigators and clinical coordinators nationwide who collected the samples and all the scientific collaborators were key to the study success. The investigators thank the patients and families who took part in the study.

"I'm proud to be a part of one of the leading ICH research teams in the country. The ability to learn deeply from surgical samples opens the door for exciting new avenues in ICH research," said Charles Matouk, MD, Chief of Neurovascular Surgery at Yale and the MISTIE III co-site PI and collaborator on the research.

The study serves as a model for future studies to leverage a brain hemorrhage clinical trial to gain significant insight into the fundamental mechanisms of the disease and provide a more targeted approach to treating ICH.

INFORMATION:

For only the second time, astronomers have linked an elusive particle called a high-energy neutrino to an object outside our galaxy. Using ground- and space-based facilities, including NASA's Neil Gehrels Swift Observatory, they traced the neutrino to a black hole tearing apart a star, a rare cataclysmic occurrence called a tidal disruption event.

"Astrophysicists have long theorized that tidal disruptions could produce high-energy neutrinos, but this is the first time we've actually been able to connect them with observational evidence," said Robert Stein, a doctoral student at the German Electron-Synchrotron (DESY) research center in ...

In a time of extreme political polarization, hearing that a political candidate has taken a stance inconsistent with their party might raise some questions for their constituents.

Why don't they agree with the party's position? Do we know for sure this is where they stand?

New research led by University of Nebraska-Lincoln political psychologist Ingrid Haas has shown the human brain is processing politically incongruent statements differently -- attention is perking up -- and that the candidate's conviction toward the stated position is also playing a role.

In other words, there is a stronger neurological response happening when, for example, a Republican takes a position favorable to new taxes, ...

Abu Dhabi, UAE, February 22, 2021: Learning more about what motivates people to join violent ideological groups and engage in acts of cruelty against others is of great social and societal importance. New research from Assistant Professor of Psychology at NYUAD Jocelyn Bélanger explores the idea of ideological obsession as a form of addictive behavior that is central to understanding why people ultimately engage in ideological violence, and how best to help them break this addiction.

In the new study, END ...

Establishing a consistent sleep schedule for a toddler can be one of the most challenging aspects of child rearing, but it also may be one of the most important.

Research findings from a team including Lauren Covington, an assistant professor in the University of Delaware School of Nursing, suggest that children with inconsistent sleep schedules have higher body mass index (BMI) percentiles. Their findings, published in the Annals of Behavioral Medicine, suggest sleep could help explain the association between household poverty and BMI.

"We've known for a while that physical activity and diet quality are very strong predictors of weight and BMI," said Covington, the lead author of the article. "I think it's really highlighting that ...

February 22, 2021 - Widely used medications for benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) - also known as enlarged prostate - may be associated with a small, but significant increase in the probability of developing heart failure, suggests a study in The Journal of Urology®, Official Journal of the American Urological Association (AUA). The journal is pub lished in the Lippincott portfolio by Wolters Kluwer.

The risk is highest in men taking a type of BPH medication called alpha-blockers (ABs), rather than a different type called 5-alpha reductase inhibitors (5-ARIs), according to the new research by D. Robert Siemens, MD, and ...

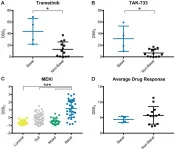

Oncotarget recently published in "MEK is a promising target in the basal subtype of bladder cancer" by Merrill, et al. which reported that while many resources exist for the drug screening of bladder cancer cell lines in 2D culture, it is widely recognized that screening in 3D culture is more representative of in vivo response.

To address the need for 3D drug screening of bladder cancer cell lines, the authors screened 17 bladder cancer cell lines using a library of 652 investigational small-molecules and 3 clinically relevant drug combinations in 3D cell culture.

Their goal was to identify compounds and classes of compounds with efficacy in bladder cancer.

Utilizing ...

An international team of scientists, including two from Oregon State University, conducted a biological assessment of the world's rivers and the limited data they found presents a fairly bleak picture.

"For the places that we have data, the situations are not really that good. There are many species that are declining, threatened or endangered," said Bob Hughes, co-author of the paper and a courtesy associate professor in Oregon State's Department of Fisheries and Wildlife. "But for most of the globe, there just is little rigorous data."

The work by Hughes and the ...

By analyzing 50 years' worth of coral reef biodiversity studies, researchers reporting in the journal Current Biology on February 22 have quantified the practice of "parachute science," which happens when international scientists, typically from higher-income countries, conduct field studies in another, typically lower-income country, without engaging with local researchers. They found that institutions from several lower-middle- and upper-middle-income countries with abundant coral reefs produced less research than institutions based in high-income countries with fewer or in some cases no reefs. They also found that host-nation scientists (scientists from the nations where field research was conducted) were ...

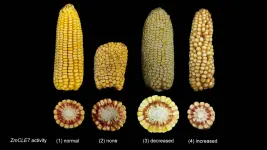

Corn--or maize--has changed over thousands of years from weedy plants that make ears with less than a dozen kernels to the cobs packed with hundreds of juicy kernels that we see on farms today. Powerful DNA-editing techniques such as CRISPR can speed up that process. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL) Professor David Jackson and his postdoctoral fellow Lei Liu collaborated with University of Massachusetts Amherst Associate Professor Madelaine Bartlett to use this highly specific technique to tinker with corn kernel numbers. Jackson's lab is one of the first to apply CRISPR to corn's very complex ...

Tracing back a ghostly particle to a shredded star, scientists have uncovered a gigantic cosmic particle accelerator. The subatomic particle, called a neutrino, was hurled towards Earth after the doomed star came too close to the supermassive black hole at the centre of its home galaxy and was ripped apart by the black hole's colossal gravity. It is the first particle that can be traced back to such a 'tidal disruption event' (TDE) and provides evidence that these little understood cosmic catastrophes can be powerful natural particle accelerators, as the team led by DESY scientist Robert Stein reports in the journal Nature Astronomy. The observations also demonstrate the power of exploring the cosmos via ...