(Press-News.org) Researchers of the University of Helsinki have resolved for the first time, how the ultrafine particles of atmosphere effect on the climate and health.

Atmospheric air pollution kills more than 10,000 people every day. The biggest threat to human health has been assumed to be the mass accumulation of atmospheric particles with diameter smaller 2.5 μm: the higher the mass and loss of visibility, the bigger the threat.

The researchers of the Institute for Atmospheric and Earth System Research (INAR) at the University of Helsinki together with collaborators in China discovered that if we want to solve the accumulation of the biggest particles, we need to start with the smallest.

Until recent studies, very little attention had been given to the ultrafine particles, smaller than 100 nm in diameter, since their weight and surface area are comparably negligible. It has been controversial whether these particles can grow to relevant sizes where they can affect visibility and human health.

"We found that the smallest particles matter the most", says Academician Markku Kulmala from the Institute for Atmospheric and Earth System Research (INAR).

The results of two studies were recently published in Faraday Discussion and Nature NPJ climate and atmospheric science.

Survival to mass relevant sizes

When there are enough precursor vapors available and when the conditions are favorable, particles forming in the atmosphere through gas-to-particle conversion at ~1 nm in diameter appear abruptly in the air. This atmospheric phenomenon known as New Particle Formation is observed in many different environments around the world.

"We are speaking of hundred thousands of particles per cubic centimeter especially in Megacities where increased population meets increased pollution", says Lubna Dada from the Institute for Atmospheric and Earth System Research (INAR).

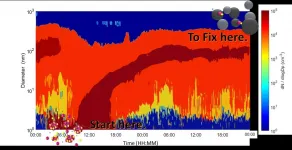

The researchers tackled the for-long controversial topic whether these smallest particles have an effect on haze formation, visibility and air pollution. In two parallel studies, they deployed the most up-to-date state-of-the-art instrumentation in the center of Beijing to tackle 'haze'.

In the first study, they followed the growth and chemical composition of the freshly formed particles from sizes ~ 1 nm until those reached sizes where they contribute to mass accumulation, in an attempt to understand the reasons behind their formation and survival to mass relevant sizes.

In the second study, the researchers deployed sophisticated instrumentation at ground level and at a 260 m and estimated the contribution of ground base sources to haze formation and accumulation.

Also the smallest matter

The results showed that In Megacities, Beijing in this case, the smallest particles are formed from gaseous sulfuric acid and ammonia or amines, which are ubiquitous. The particles grow via condensation of organics and nitrate which are equally available throughout the city.

While traffic and other anthropogenic activities do contribute to haze formation, new particle formation and growth are equally important.

In order to alleviate the air pollution problem and to reduce haze, the researchers suggest an increased attention towards the very small particles and vapors.

"It´s crucial to control the precursor vapors needed to form the particles and the vapors needed to grow them", Dada says.

A bubble preventing dilution

It was also found in the studies that new particle formation is a regional phenomenon happening over 100 of kilometers, while its amplification and growth to haze relevant sizes is rather local. The increased pollution on ground level together with amplified urbanization like high buildings create something like a bubble which separates the city from the upper atmosphere.

The more pollution is trapped in this bubble, the more stable it makes it, preventing the pollutants from being diluted into the upper atmosphere and concentrating pollution inside the city where people live. It is a runaway effect, the more pollutants are emitted the more trapping happens, making haze even worse at ground level.

"In brief, it is not only the particles that are directly emitted by anthropogenic activities such as traffic and industry need to be controlled, but also the associated vapors which are capable of forming seed particles on their own or grow those that are already present. To solve the big, we need to start small," Dada summarizes.

INFORMATION:

Publications:

Kulmala et al. (2021). Is reducing new particle formation a plausible solution to mitigate particulate air pollution in Beijing and other Chinese megacities? Faraday Discussions.

https://pubs.rsc.org/en/content/articlelanding/2021/FD/D0FD00078G#!divAbstract

Du and Dada et al. (2021). A 3D study on the amplification of regional haze and particle growth by local emissions. Nature NPJ climate and atmospheric science.

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41612-020-00156-5

More information:

Markku Kulmala

Academician, Professor, University of Helsinki

Institute for Atmospheric and Earth System Research (INAR)

markku.kulmala@helsinki.fi

+358 40 596 2311

Twitter: @MarkkuKulmala1

Lubna Dada

Doctor, Postdoctoral Researcher, University of Helsinki

Institute for Atmospheric and Earth System Research (INAR)

lubna.dada@helsinki.fi

+358 50 448 8568

Twitter: @Dadalubna

Wei Du

Doctor, Postdoctoral Researcher, University of Helsinki

Institute for Atmospheric and Earth System Research (INAR)

wei.du@helsinki.fi

A new study has for the first time explored the rate at which the world's largest fish, the endangered whale shark, can recover from its injuries. The findings reveal that lacerations and abrasions, increasingly caused through collisions with boats, can heal in a matter of weeks and researchers found evidence of partially removed dorsal fins re-growing.

This work, published in the journal Conservation Physiology, comes at a critical time for these large sharks, that can reach lengths of up to 18 metres. Other recent studies have shown that as their popularity within the wildlife tourism sector increases, so do interactions with humans and boat traffic. As a result, these ...

Huntington's disease is caused by a mutation in the Huntingtin gene (HTT), which appears in adults and features motor, cognitive and psychiatric alterations. The origin of this disease has been associated with the anomalous functioning of the mutated protein: mHTT, but recent data showed the involvement of other molecular mechanisms.

A new study conducted by the University of Barcelona has identified a type of ribonucleic acid (RNA) as a potential therapeutic target for the treatment of the disease. These are the small RNA, or sRNAs, molecules that do not code proteins but have important functions in the regulation of gene expression. According to the study, sRNAs would ...

X-ray scans revolutionised medical treatments by allowing us to see inside humans without surgery. Similarly, terahertz spectroscopy penetrates graphene films allowing scientists to make detailed maps of their electrical quality, without damaging or contaminating the material. The Graphene Flagship brought together researchers from academia and industry to develop and mature this analytical technique, and now a novel measurement tool for graphene characterisation is ready.

The effort was possible thanks to the collaborative environment enabled by the Graphene Flagship European consortium, with participation by scientists from Graphene Flagship partners DTU, Denmark, IIT, Italy, Aalto University, Finland, AIXTRON, UK, imec, Belgium, Graphenea, Spain, Warsaw ...

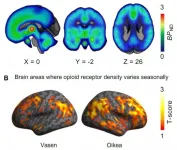

Seasons have an impact on our emotions and social life. Negative emotions are more subdued in the summer, whereas seasonal affective disorder rates peak during the darker winter months. Opioids regulate both mood and sociability in the brain.

In the study conducted at the Turku PET Centre, Finland, researchers compared how the length of daylight hours affected the opioid receptors in humans and rats.

"In the study, we observed that the number of opioid receptors was dependent on the time of the year the brain was imaged. The changes were most prominent in the brain regions that control emotions and sociability. The changes in the opioid receptors caused by the variation in the amount of daylight could be an important factor in seasonal affective disorder," ...

WASHINGTON -- Researchers have developed a new sensor that could allow practical and low-cost detection of low concentrations of methane gas. Measuring methane emissions and leaks is important to a variety of industries because the gas contributes to global warming and air pollution.

"Agricultural and waste industries emit significant amounts of methane," said Mark Zondlo, leader of the Princeton University research team that developed the sensor. "Detecting methane leaks is also critical to the oil and gas industry for both environmental and economic reasons because natural gas is mainly composed of methane."

In ...

A new study suggests that a hormone known to prevent weight gain and normalize metabolism can also help maintain healthy muscles in mice. The findings present new possibilities for treating muscle-wasting conditions associated with age, obesity or cancer, according to scientists from the University of Southern California Leonard Davis School of Gerontology.

The research, published this month in the American Journal of Physiology-Endocrinology and Metabolism, addresses the related problems of age and obesity-induced muscle loss, conditions which can lead to increased risk of falls, diabetes and other negative health impacts. It also adds to a growing number of findings describing beneficial effects of MOTS-c, ...

Scientists at the University of Adelaide have challenged the common assumption that genetic diversity of a species is a key indicator of extinction risk.

Published in the journal PNAS, the scientists demonstrate that there is no simple relationship between genetic diversity and species survival. But, Dr Joao Teixeira and Dr Christian Huber from the University of Adelaide's School of Biological Sciences conclude, the focus shouldn't be on genetic diversity anyway, it should be on habitat protection.

"Nature is being destroyed by humans at a rate never seen before," says computational biologist Dr Huber. "We burn ...

COLUMBUS, Ohio - Scientists from around the world have published more than 87,000 papers about coronavirus between the start of the COVID-19 pandemic and October 2020, a new analysis shows.

Even given the importance of the pandemic, researchers were surprised by the huge number of studies and other papers that scientists produced on the subject in such a short time.

"It is an astonishing number of publications - it may be unprecedented in the history of science," said Caroline Wagner, co-author of the study and associate professor in the John Glenn College of Public Affairs at The Ohio State University.

"Nearly all of the scientific community around the world turned its attention to this one issue."

Wagner conducted the analysis with Xiaojing Cai from Zhejiang University in ...

A team of researchers designed and manufactured a new sodium-ion conductor for solid-state sodium-ion batteries that is stable when incorporated into higher-voltage oxide cathodes. This new solid electrolyte could dramatically improve the efficiency and lifespan of this class of batteries. A proof of concept battery built with the new material lasted over 1000 cycles while retaining 89.3% of its capacity--a performance unmatched by other solid-state sodium batteries to date.

Researchers detail their findings in the Feb. 23, 2021 issue of Nature Communications.

Solid state batteries hold the promise of safer, cheaper, and longer lasting batteries. Sodium-ion chemistries are particularly promising because sodium is low-cost and abundant, as opposed ...

ROCKVILLE, MD - Coronaviruses exploit our cells so they can make copies of themselves inside us. After they enter our cells, they use our cell machinery to make unique tools of their own that help them generate these copies. By understanding the molecular tools that are shared across coronaviruses, there is potential to develop treatments that can not only work in the current COVID-19 pandemic, but in future coronavirus outbreaks as well. Rockefeller University researchers in the labs of Tarun Kapoor and Shixin Liu, including postdoctoral associate ...