(Press-News.org) New York, February 24, 2021 - Graduate Center, CUNY/Brooklyn College professor was part of a discovery of the first fossil evidence of any primate, illustrating the earliest steps of primates 66 million years ago following the mass extinction that wiped out all dinosaurs and led to the rise of mammals.

Stephen Chester, an assistant professor of anthropology and paleontologist at the Graduate Center, CUNY and Brooklyn College, was part of a team of 10 researchers from across the United States who analyzed several fossils of Purgatorius, the oldest genus in a group of the earliest-known primates called plesiadapiforms. These ancient mammals were small-bodied and ate specialized diets of insects and fruits that varied across species.

This discovery is central to primate ancestry and adds to our understanding of how life on land recovered after the Cretaceous-Paleogene extinction event 66 million years ago that wiped out all dinosaurs, except for birds. This study was documented in a paper published in the journal Royal Society Open Science.

"This discovery is exciting because it represents the oldest dated occurrence of archaic primates in the fossil record," Chester said. "It adds to our understanding of how the earliest primates separated themselves from their competitors following the demise of the dinosaurs."

Chester and Gregory Wilson Mantilla, Burke Museum Curator of Vertebrate Paleontology and University of Washington biology professor, were co-leads on this study, where the team analyzed fossilized teeth found in the Hell Creek area of northeastern Montana. The fossils, now part of the collections at the University of California Museum of Paleontology, Berkeley, are estimated to be 65.9 million years old, about 105,000 to 139,000 years after the mass extinction event.

Based on the age of the fossils, the team estimates that the ancestor of all primates (the group including plesiadapiforms and today's primates such as lemurs, monkeys, and apes) likely emerged by the Late Cretaceous--and lived alongside large dinosaurs.

"Stephen Chester's high-caliber impactful research in this area with Brooklyn College students has significantly contributed to our understanding of the environmental, biological, and social dependencies that ultimately led to the evolution of primates," said Peter Tolias, dean of the School of Natural and Behavioral Sciences.

This is not the first big find Chester has been involved with. While this latest discovery is unique in that it focused on one group of mammals--primates--in 2019, Chester, along with current collaborator Wilson Mantilla, was a key member of a groundbreaking discovery that revealed in striking detail how many life forms--including mammals, turtles, crocodiles, and plants--recovered after the asteroid impact that wiped out the dinosaurs. Chester, who specializes in the early evolutionary history of primates and other placental mammals, was also a co-author of that peer-reviewed scientific paper in Science magazine with Denver Museum of Nature & Science researchers.

In 2015, while at Brooklyn College, Chester was also the lead author on a paper published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences on this same genus of primate, Purgatorius. His co-authored paper described the ankle bones of Purgatorius, which is still the oldest fossil evidence that primates lived in the trees shortly after the extinction of the dinosaurs.

Chester did some of the research for this project at his Evolutionary Morphology Laboratory, where he trains undergraduate students in all aspects of paleontological research at Brooklyn College. While students were not directly involved in this latest discovery and subsequent paper, Chester has brought many lucky students from his paleoanthropological fieldwork classes to Wyoming, Montana, and North Dakota to a region essentially known as the "paleontological mecca of the West" to dig for primate fossils from 66 million years ago. These trips connected Brooklyn College students with Chester's scientific collaborators and other students from the Denver Museum of Nature & Science, the Smithsonian's National Museum of Natural History, the Yale Peabody Museum, the Royal Ontario Museum, and the Marmarth Research Foundation.

INFORMATION:

The team of researchers who collaborated alongside Chester and Wilson Mantilla in this latest discovery includes William Clemens, University of California Museum of Paleontology; Jason Moore, University of New Mexico; Courtney Sprain, University of Florida and University of California, Berkeley; Brody Hovatter, University of Washington; William Mitchell, Minnesota IT Services; Wade Mans, University of New Mexico; Roland Mundil, Berkeley Geochronology Center; and Paul Renne, University of California, Berkeley.

About The Graduate Center of The City University of New York

The Graduate Center, CUNY is a leader in public graduate education devoted to enhancing the public good through pioneering research, serious learning, and reasoned debate. The Graduate Center offers ambitious students more than 40 doctoral and master's programs of the highest caliber, taught by top faculty from throughout CUNY -- the nation's largest public urban university. Through its nearly 40 centers, institutes, initiatives, and the Advanced Science Research Center, The Graduate Center influences public policy and discourse and shapes innovation. The Graduate Center's extensive public programs make it a home for culture and conversation. END

According to a new study published in The American Journal of Human Genetics, more than one third of genetic variants that increase the risk of coronary artery disease regulate the expression of genes in the liver. These variants have an impact on the expression of genes regulating cholesterol metabolism, among other things. The findings provide valuable new insight into the genetics of coronary artery disease. The study was conducted in collaboration between the University of Eastern Finland, Kuopio University Hospital, the University of California Los Angeles, and the University of Arizona.

Coronary artery disease (CAD) and its most important complication ...

Australian researchers have called for additional services for survivors of intimate partner violence - warning those who have these experiences are more vulnerable to elder abuse.

Women who survive domestic violence continue to experience negative effects well into their older years but they are also more vulnerable to elder abuse, says Flinders University researcher Dr Monica Cations, lead author of the study published in the American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry.

"This is the first time this relationship has been demonstrated and tells us that older survivors need close monitoring and prevention efforts to keep them safe from further abuse."

The study looked at the psychological and physical impacts and risk for elder abuse associated ...

Before the corona pandemic, tens of millions international travellers annually headed to the tropics, getting exposed to local intestinal bacteria. A total of 20-70% of those returning from the tropics carry - for the most unknowingly - ESBL-producing bacteria resistant to multiple antibiotics. The likelihood of acquiring such superbacteria depends on destination and health behaviour abroad. The risk is greatest in South and Southeast Asia, and a substantial increase is associated with contracting travellers' diarrhoea and taking antibiotics while abroad.

An investigation led by professor ...

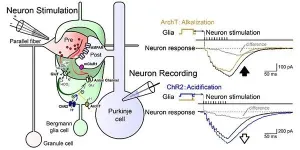

Tohoku University scientists have shown that neuronal and glial circuits form a loosely coupled super-network within the brain. Activation of the metabotropic glutamate receptors in neurons was shown to be largely influenced by the state of the glial cells. Therefore, artificial control of the glial state could potentially be used to enhance the memory function of the brain.

The findings were detailed in the Journal of Physiology.

Although the glial cells occupy more than half of the brain, they were thought to act as glue--merely filling the gap between neurons. However, recent findings show that the concentration of intracellular ions in glia, ...

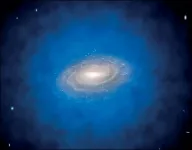

A new theoretical study has proposed a novel mechanism for the creation of supermassive black holes from dark matter. The international team find that rather than the conventional formation scenarios involving 'normal' matter, supermassive black holes could instead form directly from dark matter in high density regions in the centres of galaxies. The result has key implications for cosmology in the early Universe, and is published in Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

Exactly how supermassive black holes initially formed is one of the biggest problems in the study of galaxy evolution ...

A German-Polish research team has succeeded in creating a micrometer-sized space-time crystal consisting of magnons at room temperature. With the help of the scanning transmission X-ray microscope Maxymus at Bessy II at Helmholtz Zentrum Berlin, they were able to film the recurring periodic magnetization structure in a crystal. Published in the Physical Review Letters, the research project was a collaboration between scientists from the Max Planck Institute for Intelligent Systems in Stuttgart, Germany, the Adam Mickiewicz University and the Polish Academy of Sciences in Pozna? in Poland.

Order in space and a periodicity in time

A crystal is a solid whose atoms or molecules are regularly arranged in a particular structure. If one looks at the arrangement with a microscope, one discovers ...

Today's quantum computers contain up to several dozen memory and processing units, the so-called qubits. Severin Daiss, Stefan Langenfeld, and colleagues from the Max Planck Institute of Quantum Optics in Garching have successfully interconnected two such qubits located in different labs to a distributed quantum computer by linking the qubits with a 60-meter-long optical fiber. Over such a distance they realized a quantum-logic gate - the basic building block of a quantum computer. It makes the system the worldwide first prototype of a distributed quantum computer.

The limitations of previous qubit architectures

Quantum ...

A new study, published today in Nature Digital Medicine, found that 'natural language processing' (NLP) of information routinely recorded by doctors - as part of patients' electronic health records - reveal vital trends that could help clinical teams forecast and plan for surges in patients.

The researchers from King's College London, King's College Hospital NHS Foundation Trust (KCH), and Guy's and St Thomas' Hospital NHS Foundation Trust (GSTT), used NLP algorithms to translate the electronic notes made by doctors into a standardised, structured set of medical terms that could be analysed by a computer.

Tracking trends in patients

In the ...

Social distancing - from mobility restrictions to complete lockdowns -- can take many weeks, possibly even months, a potentially devastating outcome for social and economic stability. One of the challenges is that the sick cannot be selectively isolated, since many of the spreaders remain pre-symptomatic for a period ranging from several days to as much as two weeks - invisible spreaders who continue to be socially active. Hence, it seems that without a population-wide lockdown isolating the carriers cannot be achieved effectively.

To bypass this challenge, researchers from Israel's Bar-Ilan University, led by Prof. Baruch Barzel, devised a strategy based on alternating lockdowns: first splitting the population into two groups, then ...

LOGAN, UTAH -- One solution to agriculture's many challenges -- climate change-induced drought, less arable land, and decreased water quality, to name a few -- is to develop smarter fertilizers. Such fertilizers would aim not only to nourish the plant but also to maximize soil bacteria's positive effects on the plant. Tapping into a plant's microbiome may be the extra layer of defense crops need to thrive.

In their study published on Dec. 4 in Nature: Scientific Reports, researchers at Utah State University analyzed the effects of two abiotic stressors on Pseudomonas chlororaphis O6 (PcO6), a health-promoting bacterium native ...