(Press-News.org) While the amazing regenerative power of the liver has been known since ancient times, the cells responsible for maintaining and replenishing the liver have remained a mystery. Now, research from the Children's Medical Center Research Institute at UT Southwestern (CRI) has identified the cells responsible for liver maintenance and regeneration while also pinpointing where they reside in the liver.

These findings, reported today in Science, could help scientists answer important questions about liver maintenance, liver damage (such as from fatty liver or alcoholic liver disease), and liver cancer.

The liver performs vital functions, including chemical detoxification, blood protein production, bile excretion, and regulation of energy metabolism. Structurally, the liver is comprised of tissue units called lobules that, when cross-sectioned, resemble honeycombs. Individual lobules are organized in concentric zones in which hepatocytes, the primary liver cell type, carry out diverse functions. Over the past 10 years, there has been debate about whether all hepatocytes across the lobule contribute to the production of new cells or if a certain subset of hepatocytes or stem cells is responsible.

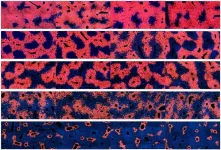

Previous efforts to identify the cells most responsible for liver regeneration were hindered by a lack of markers to distinguish and compare the functions of distinct types of hepatocytes in different regions of the liver. Scientists in the Zhu lab addressed this issue by comparing the genes that mark hepatocytes throughout the liver. Using this approach, they identified genes that were only turned on by specific subsets of hepatocytes, and then used these genes as markers to distinguish the identities and functions of different hepatocyte subsets. They created 11 new mouse strains, each of which carries a marker for a specific subset of hepatocytes. Along with three previously established mouse strains, researchers observed how the labeled cells multiplied or disappeared over time, and which were responsible for liver regeneration after damage. These experiments allowed researchers to directly compare how different subsets of hepatocytes contributed to liver maintenance and regeneration.

Members of the Zhu lab discovered that cells in zone 2 gave rise to new hepatocytes that populated all three zones of liver lobules while cells from zones 1 and 3 disappeared. These unexpected observations suggested that there is not a rare population of stem cells responsible for liver maintenance, but instead, a common set of mature hepatocytes within a specific region of the liver that regularly divide to make new hepatocytes throughout the liver. The Zhu lab also exposed mice to chemicals that mimicked common forms of liver damage, showing that cells in zone 2 were most able to evade death, regenerate hepatocytes, and sustain liver function.

"In humans, cells in zones 1 and 3 are most often harmed by alcohol, acetaminophen, and viral hepatitis. So it makes sense that cells in zone 2, which are sheltered from toxic injuries affecting either end of the lobule, would be in a prime position to regenerate the liver. However, more investigation is needed to understand the different cell types in the human liver," says Hao Zhu, M.D., an associate professor at CRI and lead author of the study.

To learn more about mechanisms that hepatocytes in zone 2 use to regenerate liver function, members of the Zhu lab performed genetic screens to look for genes important for growth and regeneration. They discovered a pathway known as the IGFBP2-mTOR-CCND1 axis that was active in zone 2 but less so in zones 1 and 3. When they deleted components of this pathway from mice, the cells in zone 2 no longer gave rise to new hepatocytes, establishing that this was the mechanism responsible for the regenerative capacity of zone 2 cells.

"The identification of zone 2 hepatocytes as a regenerative population answers some fundamental questions about liver biology and could have important implications for liver disease. In addition, the tools we created to study different types of hepatocytes can be used to examine how different cells respond to liver damage or to genetic changes that cause liver cancer," says Zhu.

INFORMATION:

Zhu is an associate professor of pediatrics and internal medicine at UT Southwestern where he holds the Kern Wildenthal, M.D., Ph.D. Distinguished Professorship in Pediatric Research. He is also a Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas (CPRIT) Scholar in Cancer Research.

The Pollack Foundation, National Institutes of Health (NIH)/National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (R01DK111588), NIH/National Cancer Institute (R01CA251928), CPRIT (RP170267, RP180268), a Burroughs Wellcome Fund Career Award for Medical Scientists, a Stand Up To Cancer Innovative Research Grant (SU2C-AACR-IRG 10-16), and donors to the Children's Medical Center Foundation supported this work.

About CRI

Children's Medical Center Research Institute at UT Southwestern (CRI) is a joint venture of UT Southwestern Medical Center and Children's Medical Center Dallas, the flagship hospital of Children's Health. CRI's mission is to perform transformative biomedical research to better understand the biological basis of disease. Located in Dallas, Texas, CRI is home to interdisciplinary groups of scientists and physicians pursuing research at the interface of regenerative medicine, cancer biology and metabolism. For more information, visit: cri.utsw.edu. To support CRI, visit: give.childrens.com/about-us/why-help/cri/

Paleo-ecologists from The University of New Mexico and at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln have demonstrated that the offspring of enormous carnivorous dinosaurs, such as Tyrannosaurus rex may have fundamentally re-shaped their communities by out-competing smaller rival species.

The study, released this week in the journal Science, is the first to examine community-scale dinosaur diversity while treating juveniles as their own ecological entity.

"Dinosaur communities were like shopping malls on a Saturday afternoon ? jam-packed with teenagers" explained Kat Schroeder, a graduate student in the UNM Department of Biology who led the study. "They made up a significant portion of the individuals in a species and would have had a very real impact ...

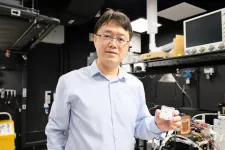

An international team of scientists has developed a system that can generate random numbers over a hundred times faster than current technologies, paving the way towards faster, cheaper, and more secure data encryption in today's digitally connected world.

The random generator system was jointly developed by researchers from Nanyang Technological University, Singapore (NTU Singapore), Yale University, and Trinity College Dublin, and made in NTU.

Random numbers are used for a variety of purposes, such as generating data encryption keys and one-time ...

As Covid-19 impacts lives around the world- a new skeleton study is reconstructing ancient pandemics to assess human's evolutionary ability to fight off leprosy, tuberculosis and treponematoses with help from declining rates of transmission when the germs became widespread.

The researchers state the germs mutated to infect ancient humans so they could replicate- hopping across to as many new hosts as possible- but the severity of the diseases reduced as a result.

The analysis by Adjunct Professor in Archaeology Maciej Henneberg and Dr Teghan Lucas at Flinders ...

In 2001, the International Human Genome Sequencing Consortium announced the first draft of the human genome reference sequence. The Human Genome Project, as it was called, had taken more than eleven years of work and involved more than 1000 scientists from 40 countries. This reference, however, did not represent a single individual but instead is a composite of humans that could not accurately capture the complexity of human genetic variation.

Building on this, scientists have carried out many sequencing projects over the last 20 years to identify and catalog genetic differences between an individual and the reference genome. Those differences usually ...

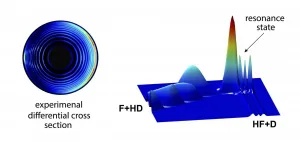

A chemical reaction can be understood in detail at the quantum state-resolved level, through a combined study of molecular crossed beam experiments and theoretical quantum molecular reaction dynamics simulations.

At a single collision condition, the molecular crossed beam apparatus is able to detect the scattering angle-resolved product with rotational state-resolution. Whereas, with accurate global potential energy surface, quantum reactive scattering theory is able to predict the corresponding reactive scattering information.

In previous studies, the chemical reaction dynamics was revealed only with the product rotational state-resolution. And the investigation of a reaction ...

Although the value of vaccines for COVID-19 may seem obvious, government action and investment in vaccines have not been commensurate with the enormous scale of benefits they offer, argue Juan Camilo Castillo and colleagues in this Policy Forum. Since even one extra month of exposure to COVID-19 kills hundreds of thousands, reduces global gross domestic product (GDP) by hundreds of billions of dollars, and generates large losses to human capital by harming education and health, expanding vaccine capacity even further would generate substantial global benefits. Castillo et al. report results of two related exercises: estimating the global benefits from vaccine capacity already in place, and estimating the benefits ...

The pandemic has made clear the threat that some viruses pose to people. But viruses can also infect life-sustaining bacteria and a Johns Hopkins University-led team has developed a test to determine if bacteria are sick, similar to the one used to test humans for COVID-19.

"If there was a COVID-like pandemic occurring in important bacterial populations it would be difficult to tell, because before this study, we lacked the affordable and accurate tools necessary to study viral infections in uncultured bacterial populations," said study corresponding author Sarah ...

Bladder cancer is more aggressive and more advanced in South Texas residents than in many parts of the country, a study by the Mays Cancer Center, home to UT Health San Antonio MD Anderson, indicates.

The disease is also deadlier in Latinos and women, regardless of where they live nationwide, according to the research.

The team from The University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio (UT Health San Antonio), which includes the Mays Cancer Center, compared bladder cancer cases in the Texas Cancer Registry with cases in the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) Program. SEER, which collects data on cancer cases from various locations and sources across the U.S., does not include Texas statistics.

Cases covered the years ...

A Skoltech researcher has developed a theoretical model of wave formation in straits and channels that accounts for nonlinear effects in the presence of a coastline. This research can improve wave prediction, making maritime travel safer and protecting coastline infrastructure. The paper was published in the journal Ocean Dynamics.

Predicting surface weather at sea has always been a challenging task with very high stakes; for instance, over 4,000 people died due to rough seas during Operation Overlord at Normandy in June 1944, an allied incursion where poor forecasting altered the course of the operation quite significantly. Current wave forecasting models used, for example, by NOAA in the US, are imperfect, but they have many tunable parameters to ensure a reasonably good prediction.

However, ...

Low blood levels of immune cells called lymphocytes, in combination with higher levels of inflammation on PET/CT scans, are indicators of active sarcoidosis -- an inflammatory disease that attacks multiple organs, particularly the lungs and lymph nodes -- which disproportionately affects African Americans. The discovery by researchers at the University of Illinois Chicago could help guide disease treatment. Their findings are published in the journal Frontiers in Medicine.

The researchers were looking for biomarkers -- both in the blood and in PET/CT scan findings -- ...