Open any anatomy textbook and you'll find the long-standing hypothesis that the evolution of the mammal backbone, which is uniquely capable of sagittal (up and down) movements, evolved from a backbone that functioned similar to that of living reptiles, which move laterally (side-to-side). This so called "lateral-to-sagittal" transition was based entirely on superficial similarities between non-mammalian synapsids, the extinct forerunners of mammals, and modern-day lizards.

In a paper published on March 2 in Current Biology, a team of researchers led by Harvard University challenge the "lateral-to-sagittal" hypothesis by measuring vertebral shape across a broad sample of living and extinct amniotes (reptiles, mammals, and their extinct relatives). Using cutting-edge techniques they map the impact of evolutionary changes in shape on the function of the vertebral column and show that non-mammalian synapsids moved their backbone in a manner that was distinctly their own and quite different from any living animal.

The team, led by first author Katrina E. Jones, former Postdoctoral Researcher, Department of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology, Harvard University, found that while the degree of sagittal bending does increase during mammal evolution, the backbones of the earliest synapsids were optimized for stiffness and the evolutionary transition to mammals did not include a stage characterized by reptile-like lateral bending. Instead they discovered that modern lizards and other reptiles have a unique backbone morphology and function that does not represent ancestral locomotion, and that the earliest ancestors of mammals did not move like a lizard, as scientists previously posited.

"The long-held idea that there was a transition in mammal evolution directly from lateral to sagittal bending is far too simple, said Senior author Stephanie Pierce, Thomas D. Cabot Associate Professor in the Department of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology and curator of vertebrate paleontology in the Museum of Comparative Zoology at Harvard University. "Lizards and mammals diverged from one another millions of years ago and they've each gone on their own evolutionary journey. We show that living lizards don't represent any sort of ancestral morphology or function that the two groups would have had in common so long ago."

Co-author Ken Angielczyk, MacArthur Curator of Paleomammalogy, Negaunee Integrative Research Center, Field Museum of Natural History, agreed, "Reptiles have been evolving just as long as mammals and because of that there's just as much time for changes and specializations to accumulate for reptiles. If you look at the vertebrae of a modern lizard or crocodile their vertebrae are actually very different from early ancestors of mammals and reptiles that lived at the same time around 300 million years ago. Both living mammals and reptiles have accumulated their own set of specializations over evolutionary time."

Jones and co-authors, including former Harvard graduate student Blake Dickson, PhD '20, began by measuring the shape of the vertebrae of a range of reptiles, mammals, salamanders, and some fossil non-mammalian synapsids. The specimens came from museum collections all over the world, with modern animal skeletons primarily from the Museum of Comparative Zoology (MCZ), and fossil synapsids from the MCZ, the Field Museum of Natural History, and various other museums in the USA, Europe, and South Africa.

"We first had to quantify the shape of the vertebrae and that's actually a little bit tricky," said Jones. "Each vertebral column is made up of multiple vertebrae and when you have different numbers of vertebrae their shapes and functions might divide up in different ways."

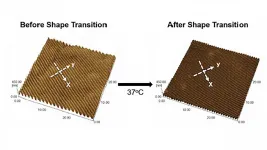

They selected five vertebrae at equivalent locations from each of the vertebral columns and measured their shapes across the different animals in three-dimension. The results showed quantitatively that non-mammalian synapsid vertebrae are very different from the vertebrae of modern mammals, and critically also from the vertebrae of lizards and other reptiles.

Next, the researchers examined how the vertebrae may have functioned using data from their previous work that compared vertebral shape to degree of vertebral motion in living lizards and mammals, providing a crucial link between form and function. The data enabled the researchers to map variation in vertebral function across the broad sample of animals, including the fossils, which allowed them to reconstruct the precise combination of functional traits that described each group of animals.

"Our team's approach to data analysis is exciting as it can reveal how different backbone shapes may result in different functional tradeoffs," Pierce said. Reptiles, for example, are very good at lateral bending, but are unable to move their spine up-and-down like mammals. "In addition to lateral and sagittal bending we also examined other functions of the backbone and then determined the optimal combination of tradeoffs for mammals, reptiles, and non-mammalian synapsids," said Pierce.

"We were able to show that non-mammalian synapsids have a different combination of functions in their backbone to both living reptiles and mammals," Jones said, "and in the course of that evolution they weren't just traversing from the reptile-like lateral to the mammal-like sagittal bending, they were actually on a completely distinctive path in which they were evolving from a separate condition."

"The historical expectation is that the synapsid ancestors of mammals were making the same set of tradeoffs that modern reptiles do. But it turns out that they have an entirely different set of tradeoffs," Angielczyk said. "The expectation that reptiles would retain ancestral locomotor patterns that existed over 320 million years ago is too simple."

The results show the backbones of non-mammalian synapsids were actually quite stiff and completely unlike those of lizards which are very compliant in the lateral direction. Further, during the evolution of mammals, new functions were added to this stiff ancestral foundation, including sagittal bending in the posterior back and twisting up front. The addition of these new functions was pivotal in building the functionally diverse mammalian backbone, allowing modern-day mammals to run really fast and rotate their spine to groom their fur.

"By rigorously analyzing the fossil record, we are able to reject the simplistic lateral-to-sagittal hypothesis for a much more complex and interesting evolution story," Pierce said. "We are now revealing the evolutionary path towards the formation of the unique mammalian backbone."

The study is part of a series of ongoing projects on the evolution of the mammal backbone, piecing together its development, morphology, function, and evolution. "We still don't have the whole story," said Jones, "but we are getting close."

The researchers are now using three-dimensional modeling of the vertebrae to understand how the ancestors of mammals moved. "We are now testing our previous studies with CAD assisted three-dimensional models," said Jones. "So far it's working quite well and appears to support what we found in this paper."

INFORMATION:

Katrina E. Jones is currently Presidential Fellow at the University of Manchester, UK.

Blake Dickson is currently a postdoctoral researcher in the Department of Evolutionary Anthropology at Duke University.

Article and author details

Katrina E. Jones, Blake v. Dickson, Kenneth D. Angielczyk, Stephanie E. Pierce. 2021. Adaptive landscapes challenge the "lateral-sagittal" paradigm for mammal vertebral evolution. Current Biology DOI: 10.1016/j.cub.2021.02.009

Corresponding author(s)

Katrina E. Jones,

katrinajones@fas.harvard.edu

Stephanie E. Pierce,

spierce@oeb.harvard.edu