(Press-News.org) There's more to taste than flavor. Let ice cream melt, and the next time you take it out of the freezer you'll find its texture icy instead of the smooth, creamy confection you're used to. Though its flavor hasn't changed, most people would agree the dessert is less appetizing.

UC Santa Barbara Professor Craig Montell and postdoctoral fellow Qiaoran Li have published a study in Current Biology providing the first description of how certain animals sense the texture of their food based on grittiness versus smoothness. They found that, in fruit flies, a mechanosensory channel relays this information about a food's texture.

The channel, called TMEM63, is part of a class of receptors that appear in organisms from plants to humans. As a result, the new findings could help shed light on some of the nuances of our own sense of taste.

"We all appreciate that food texture impacts food appeal," said Montell, Duggan and Distinguished Professor in the Department of Molecular, Cellular, and Developmental Biology. "But this is something that we don't understand very well."

Li and Montell focused on fruit flies to investigate the molecular and cellular mechanisms behind the effect of grittiness on food palatability. "We found that they, like us, have food preferences that are influenced by this textural feature," Montell said. They devised a taste test in which they added small particles of varying size to sugary food, finding that the flies preferred particles of a specific size.

In prior work, Montell and his group have elucidated the nuances at play in the sense of taste. In 2016, they found a channel that enables flies to sense the hardness and viscosity of their food by the movement of the small bristles on their tongue, or labellum. More recently they discovered the mechanisms by which cool temperatures reduce palatability.

Now the researchers sought to identify a receptor that's required for sensing grittiness. They figured that it would be a mechanically-activated channel triggered when particles lightly bent a fly's taste hairs. However, the inactivation of known receptors had no impact on preference for food based on smoothness and grittiness.

The authors then considered the protein TMEM63. "Fly TMEM63 is part of a class of mechano-sensors conserved from plants to humans," Montell said, "but its roles in animals were unknown."

With only the suspicion that it might relay information about grittiness, Li and Montell inactivated the gene that codes for TMEM63 and compared the behavior of the mutant flies with wild-type animals.

After withholding food from the animals for a couple hours, the researchers measured their interest in various sugar solutions mixed with particles of different sizes. They used the amount that the fly extended its proboscis to measure the animal's interest in the food it was presented. Li and Montell discovered that without TMEM63, the flies couldn't distinguish between a solution of pure sugar water and one containing small silica spheres around 9 micrometers in diameter, which is the flies' preferred level of grittiness.

When they added chemicals to make the sugar solution less pleasant -- a mild acid, caffeine or moderate amounts of salt -- the microspheres reversed the flies' aversion. But not in flies lacking TMEM63. Upon restoring the gene that codes for this channel in the mutant flies' labella, the animals regained their ability to detect grittiness.

"It wasn't known before this study that flies could even discriminate foods on the basis of grittiness," Montell noted. "Now that we found that the mechanosensitive channel is TMEM63, we have uncovered one role for this protein in an animal."

The TMEM63 channel functions in a single multi-dendritic neuron (md-L) in each of two labella at the end of the fly's proboscis. The neuron senses movements of most of the taste bristles on the labella. When the bristles move slightly upon interacting with food particle, it activates the TMEM63 channel, which stimulates the neuron that relays the sensation to the brain. Because one neuron connects to many bristles, it likely can't convey positional data of individual particles, only a gestalt sense of grittiness.

By applying light force to these bristles -- mimicking the action of small particles in a gritty solution -- Montell and Li could activate the md-L neuron. However, the same procedure showed no effect in flies with TMEM63 knocked out. Interestingly, both groups of animals could detect larger forces on their bristles, such as might be caused by hard or viscous foods.

Montell's team had previously shown that another channel called TMC, which is also expressed in md-L neurons, is important for detecting these larger forces. Both TMEM63 and TMC relay textural information about food, and even activate the same neuron. However, Li and Montell's results revealed that the two channels have distinct roles.

Texture can provide a lot of information about food. It can indicate freshness or spoilage. For instance, fruit often become mealy when they start to spoil. "Animals use all the sensory information that they can to evaluate the palatability of food," Montell said. "This includes not only its chemical makeup, but color, smell, temperature and a variety of textural features.

"The 9 micrometer particle size that flies most enjoy corresponds in size to some of their preferred foods, like budding yeast and the particles in their favorite fruit," he explained.

Montell suggested TMEM63 almost certainly has many other roles in animals. "This protein is conserved in humans," Montell said. "We don't know if it has a role in texture sensation in humans, but some kind of mechanically-sensitive channel probably does."

INFORMATION:

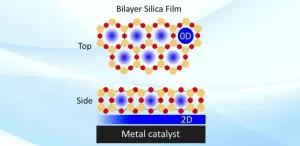

UPTON, NY--Physically confined spaces can make for more efficient chemical reactions, according to recent studies led by scientists from the U.S. Department of Energy's (DOE) Brookhaven National Laboratory. They found that partially covering metal surfaces acting as catalysts, or materials that speed up reactions, with thin films of silica can impact the energies and rates of these reactions. The thin silica forms a two-dimensional (2-D) array of hexagonal-prism-shaped "cages" containing silicon and oxygen atoms.

"These porous silica frameworks are the thickness of only three atoms," explained Samuel Tenney, a chemist in the Interface Science and ...

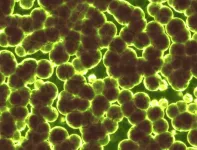

AMES, Iowa - Vaccines are an important tool in fighting porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome (PRRS), but the fast-mutating virus that causes the disease sometimes requires the production of autogenous vaccines tailored to particular variants.

The production of autogenous vaccines depends on the ability of scientists to isolate the virus, but sometimes that's a tricky process. A new study from an Iowa State University researcher shows that a new cell line may offer a better alternative to the cell line most commonly used to isolate the PRRS virus. That could lead to more reliable processes for creating autogenous vaccines, but most autogenous vaccine producers would have to make dramatic changes to their processes ...

For nearly a century, improvement in human healthcare has depended heavily on the efficiency with which we can treat bacterial diseases. But today, antibiotic resistance--the ability of certain mutant super-bacteria to block out antibiotics--poses a major threat to healthcare, food security, and overall social development worldwide, threatening to upend much of the progress our civilization has achieved.

Scientists are now urgently attempting to tackle this problem from various angles. Professor Yunho Lee at Gwangju Institute of Science and Technology (GIST), Korea, whose contribution is published in the American Chemical Society's Environmental Science and Technology, is looking at it from the point of view of his field of research--wastewater ...

If you're looking for an indoor space with a low level of particulate air pollution, a commercial airliner flying at cruising altitude may be your best option. A newly reported study of air quality in indoor spaces such as stores, restaurants, offices, public transportation -- and commercial jets -- shows aircraft cabins with the lowest levels of tiny aerosol particles.

Conducted in July 2020, the study included monitoring both the number of particles and their total mass across a broad range of indoor locations, including 19 commercial flights in which measurements took place throughout ...

Finding innovative and sustainable solutions to our material needs is one of the core objectives of green chemistry. The myriad plastics that envelop our daily life - from mattresses to food and cars - are mostly made from oil-based monomers which are the building blocks of polymers. Therefore, finding bio-based monomers for polymer synthesis is attractive to achieve more sustainable solutions in materials development.

In a paper published in ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering, researchers from the Kleij group present a new route to prepare biobased polyesters with tuneable properties. The researchers ...

Insects can reprogram plant growth, transforming ordinary plant parts into intricately patterned shelters that are safe havens for feeding and reproduction.

These structures, called galls, have fascinated biologists for centuries. They're crafted by a variety of insects, including some species of aphids, mites, and wasps. And they take on innumerable forms, each specific in shape and size to the insect species that's created it - from knobs to cone-shaped protrusions to long, thin spikes. Some even resemble flowers.

Insects create galls by manipulating the development of plants, but figuring out exactly how they perform this feat "feels like ...

The backbone is the Swiss Army Knife of mammal locomotion. It can function in all sorts of ways that allows living mammals to have remarkable diversity in their movements. They can run, swim, climb and fly all due, in part, to the extensive reorganization of their vertebral column, which occurred over roughly 320 million years of evolution.

Open any anatomy textbook and you'll find the long-standing hypothesis that the evolution of the mammal backbone, which is uniquely capable of sagittal (up and down) movements, evolved from a backbone that functioned ...

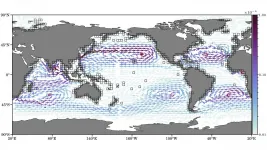

WASHINGTON, March 2, 2021 -- Tons of plastic debris get released into the ocean every day, and most of it accumulates within the middle of garbage patches, which tend to float on the oceans' surface in the center of each of their regions. The most infamous one, known as the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, is in the North Pacific Ocean.

Researchers in the U.S. and Germany decided to explore which pathways transport debris from the coasts to the middle of the oceans, as well as the relative strengths of different subtropical gyres in the oceans and how they influence long-term accumulation of debris.

In Chaos, from AIP Publishing, Philippe Miron, Francisco Beron-Vera, Luzie Helfmann, and Peter Koltai report creating a Markov chain ...

What The Study Did: This study investigates emergency department visits for violence-related injuries occurring at home and outside the home in Cardiff, Wales, before and after COVID-19 lockdown measures were instituted in March 2020.

Authors: Jonathan P. Shepherd, Ph.D., Crime and Security Research Institute at Cardiff University in Wales, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jama.2020.25511)

Editor's Note: Please see the article for additional information, including other authors, author contributions ...

In a mouse study, Australian researchers have mapped out what happens behind the scenes in fat tissue during intermittent fasting, showing that it triggers a cascade of dramatic changes, depending on the type of fat deposits and where they are located around the body.

Using state-of-the-art instruments, University of Sydney researchers discovered that fat around the stomach, which can accumulate into a 'protruding tummy' in humans, was found to go into 'preservation mode', adapting over time and becoming more resistant to weight loss.

The findings are published today in Cell Reports.

A research team led by Dr Mark Larance examined fat tissue types from different locations to understand their role during every-other-day fasting, ...