(Press-News.org) When it comes to the evolution of the mammal spine -- think of animals whose backbone allows them to gallop, hop, swim, run, or walk upright -- a key part of the tale is quite simple.

Because nonmammalian synapsids, the extinct forerunners to mammals, had similar traits to living reptiles (like having their limbs splayed out to the side instead of tucked into their body like today's mammals), the strongheld belief was that they must have also moved in similar ways. Primarily, their backbones must have moved side-to-side, bending like those of modern lizards, instead of the up-and-down bending motion mammal spines are known for. It's believed over time, and in response to selective pressures, the mammal spine evolved from that lizard like side-to-side bending to the mammal-like up-and-down bending seen today. The transition is known as the lateral-to-sagittal paradigm.

It's an easy to grasp story that's been taught in college textbooks on anatomy and evolution for decades. But, according to a new Harvard-led study, that long held belief is wrong.

"The problem with the original story was that, as opposed to being based on fossil evidence, it was primarily based just on a correlation with something else that was seen in living animals," said former Harvard postdoctoral researcher Katrina Jones. "It relied upon this assumption that these forerunners of mammals must function the same as lizards because this one aspect of their anatomy was similar to lizards.... We're saying just because the limb posture looked similar doesn't mean they moved the same."

The work, led by Jones, challenges the lateral-to-sagittal hypothesis by looking at the vertebrae of modern reptiles, mammals, and the extinct nonmammalian synapsids to determine how their vertebrae changed over time and its effect on how these creatures likely moved.

The analysis demonstrates the three lineages differ from one another other when it comes to the morphology, function, and characteristics of their spines, and suggests that mammal backbones didn't evolve from a reptile-like ancestor. There had to have been a completely different type of backbone function not observed in today's living vertebrates.

"The ancestral stock that mammals evolved from didn't look or function like a living reptile," said Stephanie Pierce, Thomas D. Cabot Associate Professor of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology and curator of vertebrate paleontology in the Museum of Comparative Zoology and the study's senior author. "They started off with their own unique set of characteristics and functions and then evolved towards mammals."

The study published in Current Biology on March 2.

It included collaborators Kenneth Angielczyk at the Field Museum of Natural History and Blake Dickson, Ph.D. '20 who worked in the Pierce lab as a graduate student but is now a postdoctoral researcher at Duke University.

Dickson's earlier work with the lab, reconstructing the evolution of terrestrial movement in early tetrapods by analyzing 3D scans of fossils, provided the method the researchers modified for the new study.

The team wanted to see how the origin story of the mammalian backbone, which comes in all shapes and sizes, held up under intense scrutiny.

They took CT scans of the spine of reptiles, mammals, and fossil nonmammalian synapsids to get 3D reconstructions of key portions of their backbones to see their shape. They then used statistical comparisons of those shapes and measured of how they bent to determine how they functioned and what movement they allowed.

They saw that the nonmammalian synapsids clearly had their own vertebral shapes and that they were distinct from both mammals and reptiles. This showed that key parts of the spine belonging to the ancestors of mammals had their own unique characteristics that are not seen in any living group.

When comparing function of the different spines, the researchers saw the nonmammalian synapsid spine acted very differently from both mammals and reptiles. Its dominant trait, was being very stiff with more limited capacity for lateral bending, unlike the lateral bending in the back of reptile spines. That suggested the long-held notion that these creatures moved like today's reptiles, particularly lizards, is wrong.

Looking at the spines of the living mammals they sampled, they saw that they were a sort of a jack-of-all-trades, displaying abilities in each of the functional traits they measured. This means that mammal backs can do much more than just sagittal bending, and that during their evolutionary history other functions were added to the stiff backs of their forerunners, such as spinal twisting for grooming fur. The results make the simple lateral-to-sagittal paradigm a much more complicated story.

The researchers cited advances in today's CT scanning technology, computational data, and statistical programs with making the study possible. They are currently working on further confirming their findings and creating full 3D spinal reconstructions for the species they looked at.

The group believes the work shows the power of the fossil record for testing long-held evolutionary ideas.

"If we only look at modern animals, such as living mammals and reptiles, we can come up with evolutionary hypotheses but they may not be correct," Pierce said. "Unless we go back into the fossil record and really dig into those extinct animals, we can't trace what those anatomical changes were, when they happen, or what selective pressures drove their evolution."

INFORMATION:

UNIVERSITY PARK, Pa. -- By modeling wolves in Yellowstone National Park, researchers have discovered that how a population is organized into social groups affects the spread of infectious diseases within the population. The findings may be applicable to any social species and could be useful in the protection of endangered species that suffer from disease invasion.

Like other social carnivores, wolves tend to form territorial social groups that are often aggressive toward each other and may lead to fatalities. During these encounters, infectious diseases -- like mange and canine distemper -- can spread between groups, which can further reduce the number of individuals in a group.

"Previous social group-disease models have assumed that groups do not change ...

WESTMINSTER, Colorado - March 02, 2021 - Herbicide-resistant weeds have fueled a growing demand for effective, nonchemical weed controls. Among the techniques used are chaff carts, impact mills and other harvest-time practices that remove or destroy weed seeds instead of leaving them on the field to sprout.

A recent article in the journal Weed Science explores whether such harvest-time controls would be effective against downy brome, Italian ryegrass, feral rye and rattail fescue - weeds that compete with winter wheat in the Pacific Northwest. Researchers set out to determine whether ...

New research has found that shrimp like creatures on the South Coast of England have 70 per cent less sperm than less polluted locations elsewhere in the world. The research also discovered that individuals living in the survey area are six times less numerous per square metre than those living in cleaner waters.

This discovery, published today in Aquatic Toxicology, mirrors similar findings in other creatures, including humans. The scientist leading research at the University of Portsmouth believes pollutants might be to blame, further highlighted by this ...

Resveratrol is a plant compound found primarily in red grapes and Japanese knotweed. Its synthetic variant has been approved as a food ingredient in the EU since 2016. At least in cell-based test systems, the substance has anti-inflammatory properties. A recent collaborative study by the Leibniz Institute for Food Systems Biology at the Technical University of Munich and the Institute of Physiological Chemistry at the University of Vienna has now shown that the bitter receptor TAS2R50 is involved in this effect. The team of scientists led by Veronika Somoza ...

CHICAGO, March 2, 2021 -- More than 70 percent of dentists surveyed by the American Dental Association (ADA) Health Policy Institute are seeing an increase of patients experiencing teeth grinding and clenching, conditions often associated with stress. This is an increase from ADA data released in the fall that showed just under 60 percent of dentists had seen an increase among their patients.

"Our polling has served as a barometer for pandemic stress affecting patients and communities seen through the eyes of dentists," said Marko Vujicic, Ph.D., chief economist and vice president of the ADA Health Policy Institute. "The increase over time suggests stress-related conditions have become substantially more prevalent since the onset of COVID-19."

The ...

BOSTON - Lymph nodes in the armpit area can become swollen after a COVID-19 vaccination, and this is a normal reaction that typically goes away with time. Radiologists at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) who recently published an approach to managing this situation in women who receive mammograms for breast cancer screening in the American Journal of Roentgenology have now expanded their recommendations to include care for patients who undergo other imaging tests for diverse medical reasons. Their guidance is published in the Journal of the American College of Radiology.

"Our ...

A new study published today in the journal Geophysical Research Letters used NASA's ice-measuring laser satellite to identify atmospheric river storms as a key driver of increased snowfall in West Antarctica during the 2019 austral winter.

These findings from scientists at Scripps Institution of Oceanography at the University of California San Diego and colleagues will help improve overall understanding of the processes driving change in Antarctica, and lead to better predictions of sea-level rise. The study was funded by NASA, with additional support from the Rhodium Group's Climate Impact Lab, a consortium ...

CLEVELAND - Researchers from Cleveland Clinic's Global Center for Pathogen Research & Human Health have developed a promising new COVID-19 vaccine candidate that utilizes nanotechnology and has shown strong efficacy in preclinical disease models.

According to new findings published in mBio, the vaccine produced potent neutralizing antibodies among preclinical models and also prevented infection and disease symptoms in the face of exposure to SARS-CoV-2 (the virus that causes COVID-19). An additional reason for the vaccine candidate's early appeal is that it may be thermostable, which would make it easier to transport and store than currently authorized COVID-19 ...

There's more to taste than flavor. Let ice cream melt, and the next time you take it out of the freezer you'll find its texture icy instead of the smooth, creamy confection you're used to. Though its flavor hasn't changed, most people would agree the dessert is less appetizing.

UC Santa Barbara Professor Craig Montell and postdoctoral fellow Qiaoran Li have published a study in Current Biology providing the first description of how certain animals sense the texture of their food based on grittiness versus smoothness. They found that, in fruit flies, a mechanosensory channel relays this information about a food's texture.

The channel, called TMEM63, is part of ...

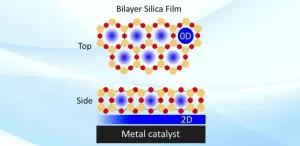

UPTON, NY--Physically confined spaces can make for more efficient chemical reactions, according to recent studies led by scientists from the U.S. Department of Energy's (DOE) Brookhaven National Laboratory. They found that partially covering metal surfaces acting as catalysts, or materials that speed up reactions, with thin films of silica can impact the energies and rates of these reactions. The thin silica forms a two-dimensional (2-D) array of hexagonal-prism-shaped "cages" containing silicon and oxygen atoms.

"These porous silica frameworks are the thickness of only three atoms," explained Samuel Tenney, a chemist in the Interface Science and ...