The issue of whether our real-life pandemic virus, SARS-CoV-2, is "airborne" is predictably more complex. The current body of evidence suggests that COVID-19 primarily spreads through respiratory droplets - the small, liquid particles you sneeze or cough, that travel some distance, and fall to the floor. But consensus is mounting that, under the right circumstances, smaller floating particles called aerosols can carry the virus over longer distances and remain suspended in air for longer periods. Scientists are still determining SARS-CoV-2's favorite way to travel.

That the science was lacking on how COVID-19 spreads seemed apparent a year ago to Tami Bond, professor in the Department of Mechanical Engineering and Walter Scott, Jr. Presidential Chair in Energy, Environment and Health. As an engineering researcher, Bond spends time thinking about the movement and dispersion of aerosols, a blanket term for particles light and small enough to float through air - whether cigarette smoke, sea spray, or hair spray.

"It quickly became clear there was some airborne component of transmission," Bond said. "A virus is an aerosol. Health-wise, they are different than other aerosols like pollution, but physically, they are not. They float in the air, and their movement depends on their size."

The rush for scientific understanding of the novel coronavirus has focused - understandably - on biological mechanisms: how people get infected, the response of the human body, and the fastest path to a vaccine. As an aerosol scientist, Bond went a different route, convening a team at Colorado State University that would treat the virus like any other aerosol. This team, now published in Environmental Science and Technology, set out to quantify the dynamics of how aerosols like viruses travel from one person to another, under different circumstances.

The cross-section of expertise to answer this question existed in droves at CSU, Bond found. The team she assembled includes epidemiologists, aerosol scientists, and atmospheric chemists, and together they created a new tool for defining how infectious pathogens, including SARS-CoV-2, transport in the air.

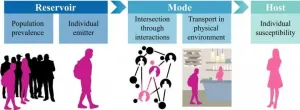

Effectively rebreathed air Their tool is a metric they're calling Effective Rebreathed Volume, or simply, the amount of exhaled air from one person that, by the time it travels to the next person, contains the same number of particles. Treating virus-carrying particles agnostically like any other aerosol allowed the team to make objective, physics-based comparisons between different modes of transmission, accounting for how sizes of particles would affect the number of particles that traveled from one person to another.

They looked at three size categories of particles that cover a biologically relevant range: 1 micron, 10 microns, and 100 microns -- about the width of a human hair. Larger droplets expelled by sneezing would be closer to the 100-micron region. Particles closer to the size of a single virion would be in the 1-micron region. Each have very different air-travel characteristics, and depending on the size of the particles, different mitigation measures would apply, from opening a window, to increasing fresh air delivery with through an HVAC system.

They compiled a set of models to compare different scenarios. For example, the team compared the effective rebreathed volume of someone standing outdoors 6 feet away, to how long it would take someone to rebreathe the same amount of air indoors but standing farther away.

Confinement matters The team found that distancing indoors, even 6 feet apart, isn't enough to limit potentially harmful exposures, because confinement indoors allows particle volumes to build up in the air. Such insights aren't revelatory, in that most people avoid confinement in indoor spaces and generally feel safer outdoors. What the paper shows, though, is that the effect of confinement indoors and subsequent particle transport can be quantified, and it can be compared to other risks that people find acceptable, Bond said.

Co-authors Jeff Pierce in atmospheric science and Jay Ham in soil and crop sciences helped the team understand atmospheric turbulence in ways that could be compared in indoor and outdoor environments.

Pierce said he sought to constrain how the virus-containing particles disperse as a function of distance from the emitting person. When the pandemic hit last year, the public had many questions about whether it was safe to run or bike on trails, Pierce said. The researchers found that longer-duration interactions outdoors at greater than 6-foot distances appeared safer than similar-duration indoor interactions, even if people were further apart indoors, due to particles filling the room rather than being carried away by wind.

"We started fairly early on in the pandemic, and we were all filled with questions about: 'Which situations are safer than others?' Our pooled expertise allowed us to find answers to this question, and I learned a lot about air filtration and air exchange in my home and in my CSU classroom," Pierce said.

More to learn What remains unclear is which size particles are most likely to cause COVID-19 infection.

Viruses can be carried on droplets large and small, but there is likely a "sweet spot" between droplet size; ability to disperse and remain airborne; and desiccation time, all of which factor into infective potential, explained Angela Bosco-Lauth, paper co-author and assistant professor in biomedical sciences.

The paper includes an analysis of the relative infection risk of different indoor and outdoor scenarios and mitigation measures, depending on the numbers of particles being inhaled.

"The problem we face is that we still don't know what the infectious dose is for people," Bosco-Lauth said. "Certainly, the more virus present, the higher the risk of infection, but we don't have a good model to determine the dose for people. And quantifying infectious virus in the air is tremendously difficult."

Follow-up pursuits The team is now pursuing follow-up questions, like comparing different mitigation measures for reducing exposures to viruses indoors. Some of these inquiries fall into the category of "stuff you already know, but with numbers," Bond said. "People are now thinking, OK, more ventilation is better, or remaining outside is better, but there is not a lot of quantification and numbers behind those recommendations," Bond said.

Bond hopes the team's work can lay a foundation for more up-front quantification of transmission dynamics in the unfortunate event of another pandemic. "This time, there was a lot of guessing at the beginning, because the science of transmission wasn't fully developed," she said. "There shouldn't be a next time."

INFORMATION:

The paper is titled "Quantifying proximity, confinement, and interventions in disease outbreaks: A decision support framework for air-transported pathogens," and is available by open access. The authors are: Tami C. Bond, Angela Bosco-Lauth, Delphine K. Farmer, Paul W. Francisco, Jeffrey R. Pierce, Kristen M. Fedak, Jay M. Ham, Shantanu H. Jathar and Sue VandeWoude.

Link to paper: https://pubs.acs.org/doi/abs/10.1021/acs.est.0c07721

CDC brief on airborne SARS-CoV-2 transmission: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/more/scientific-brief-sars-cov-2.html