Food for thought: New maps reveal how brains are kept nourished

Micro-scale depictions solve century-old puzzle of brain energy use and blood vessel clusters

2021-03-02

(Press-News.org) Our brains are non-stop consumers. A labyrinth of blood vessels, stacked end-to-end comparable in length to the distance from San Diego to Berkeley, ensures a continuous flow of oxygen and sugar to keep our brains functioning at peak levels.

But how does this intricate system ensure that more active parts of the brain receive enough nourishment versus less demanding areas? That's a century-old problem in neuroscience that scientists at the University of California San Diego have helped answer in a newly published study.

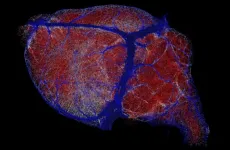

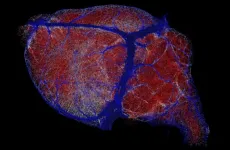

Studying the brains of mice, a team of researchers led by Xiang Ji, David Kleinfeld and their colleagues has deciphered the question of brain energy consumption and blood vessel density through newly developed maps that detail brain wiring to a resolution finer than a millionth of a meter, or one-hundredth of the thickness of a human hair.

A result of work at the crossroads of biology and physics, the new maps provide novel insights into these "microvessels" and their various functions in blood supply chains. The techniques and technologies underlying the results are described March 2 in the journal Neuron.

"We developed an experimental and computational pipeline to label, image and reconstruct the microvascular system in whole mouse brains with unprecedented completeness and precision," said Kleinfeld, a professor in the UC San Diego Department of Physics (Division of Physical Sciences) and Section of Neurobiology (Division of Biological Sciences). Kleinfeld says the effort was akin to reverse engineering nature. "This allowed Xiang to carry out sophisticated calculations that not just related brain energy use to vessel density, but also predicted a tipping point between the loss of brain capillaries and a sudden drop in brain health."

Questions surrounding how blood vessels carry nourishment to active and less active regions were posed as a general issue in physiology as far back as 1920. By the 1980s, a technology known as autoradiography, the predecessor of modern-day positron emission tomography (PET), allowed scientists to measure the distribution of sugar metabolism across the mouse brain.

To fully grasp and solve the problem, Ji, Kleinfeld and their colleagues at the Howard Hughes Medical Institute's Janelia Research Campus and UC San Diego Jacobs School of Engineering filled 99.9 percent of the vessels in the mouse brain--a count of nearly 6.5 million--with a dye-labeled gel. They then imaged the full extent of the brain with sub-micrometer precision. This resulted in fifteen trillion voxels, or individual volumetric elements, per brain, that were transformed into a digital vascular network that could be analyzed with the tools of data science.

With their new maps in hand, the researchers determined that the concentration of oxygen is roughly the same in every region of the brain. But they found that small blood vessels are the key components that compensate for varying energy requirements. For example, white matter tracts, which transfer nerve impulses across the two brain hemispheres and to the spinal cord, are regions of low energy needs. The researchers identified lower levels of blood vessels there. By contrast, brain regions that coordinate the perception of sound use three times more energy and, they discovered, were found with a much greater level of blood vessel density.

"In the era of increasing complexities being unraveled in biological systems, it is fascinating to observe the emergence of shared simple and quantitative design rules underlaying the seemingly complicated networks across mammalian brains," said Ji, a graduate student in physics.

Up next, the researchers hope to drill down into the finer aspects of their new maps to determine the detailed patterns of blood flow into and out from the entire brain. They will also pursue the largely uncharted relationship between the brain and the immune system.

INFORMATION:

Authors on the paper include Xiang Ji, Tiago Ferreira, Beth Friedman, Rui Liu, Hannah Liechty, Erhan Bas, Jayaram Chandrashekar and David Kleinfeld.

[Attachments] See images for this press release:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-03-02

When you think about your carbon footprint, what comes to mind? Driving and flying, probably. Perhaps home energy consumption or those daily Amazon deliveries. But what about watching Netflix or having Zoom meetings? Ever thought about the carbon footprint of the silicon chips inside your phone, smartwatch or the countless other devices inside your home?

Every aspect of modern computing, from the smallest chip to the largest data center comes with a carbon price tag. For the better part of a century, the tech industry and the field of computation ...

2021-03-02

Imagine you're driving up a hill toward a traffic light. The light is still green so you're tempted to accelerate to make it through the intersection before the light changes. Then, a device in your car receives a signal from the controller mounted on the intersection alerting you that the light will change in two seconds -- clearly not enough time to beat the light. You take your foot off the gas pedal and decelerate, saving on fuel. You feel safer, too, knowing you didn't run a red light and potentially cause a collision in the intersection.

Connected and automated vehicles, which can interact vehicle to vehicle (V2V) and between vehicles and roadway ...

2021-03-02

Type 2 diabetes, once considered an adult disease, is increasingly causing health complications among American youth. A research review published in the Journal of Osteopathic Medicine suggests physicians should work to more aggressively prevent pediatric diabetes.

Because few pediatric Type 2 diabetes treatment options are available, prevention is unusually important. To improve health outcomes, the paper's authors recommend physicians conduct regular screenings of children and adolescents, adopt a high level of suspicion, and intervene early and often with families who have children at risk for prediabetes and T2 diabetes.

"Pediatric type 2 diabetes is more progressive and aggressive than adult-onset Type 2 diabetes," ...

2021-03-02

Boulder, Colo., USA: Several articles were published online ahead of print

for GSA Bulletin in February. Topics include earthquake cycles in

southern Cascadia, fault dynamics in the Gulf of Mexico, debris flow after

wildfires, the assembly of Rodinia, and the case for no ring fracture in

Mono basin.

Jurassic evolution of the Qaidam Basin in western China: Constrained by

stratigraphic

succession, detrital zircon U-Pb geochronology and Hf isotope analysis

Tao Qian; Zongxiu Wang; Yu Wang; Shaofeng Liu; Wanli Gao ...

Abstract:

The formation and evolution of an intracontinental basin triggered via the

subduction or collision of plates at continental margins can record

intracontinental tectonic processes. As a typical ...

2021-03-02

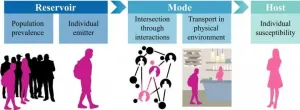

In the 1995 movie "Outbreak," Dustin Hoffman's character realizes, with appropriately dramatic horror, that an infectious virus is "airborne" because it's found to be spreading through hospital vents.

The issue of whether our real-life pandemic virus, SARS-CoV-2, is "airborne" is predictably more complex. The current body of evidence suggests that COVID-19 primarily spreads through respiratory droplets - the small, liquid particles you sneeze or cough, that travel some distance, and fall to the floor. But consensus is mounting that, under the right circumstances, smaller floating particles called aerosols can carry the virus over longer distances and remain ...

2021-03-02

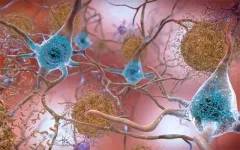

Amyloid plaques are pathological hallmarks of Alzheimer's disease (AD) -- clumps of misfolded proteins that accumulate in the brain, disrupting and killing neurons and resulting in the progressive cognitive impairment that is characteristic of the widespread neurological disorder.

In a new study, published March 2, 2021 in the Journal of Experimental Medicine (JEM), researchers at University of California San Diego School of Medicine, Massachusetts General Hospital and elsewhere have identified a new drug that could prevent AD by modulating, rather than inhibiting, a key enzyme involved ...

2021-03-02

WEST LAFAYETTE, Ind. -- When quantum computers become more powerful and widespread, they will need a robust quantum internet to communicate.

Purdue University engineers have addressed an issue barring the development of quantum networks that are big enough to reliably support more than a handful of users.

The method, demonstrated in a paper published in Optica, could help lay the groundwork for when a large number of quantum computers, quantum sensors and other quantum technology are ready to go online and communicate with each other.

The team deployed a programmable switch to adjust how much data goes to each ...

2021-03-02

Scientists regularly use remote sensing drones and satellites to record how climate change affects permafrost thaw rates -- methods that work well in barren tundra landscapes where there's nothing to obstruct the view.

But in boreal regions, which harbor a significant portion of the world's permafrost, obscuring vegetation can stymy even the most advanced remote sensing technology.

In a study published in January, researchers in Germany and at the University of Alaska Fairbanks' Geophysical Institute developed a method of using satellite imagery to measure the depth of thaw directly above permafrost in boreal ecosystems. Rather than trying to peer past ...

2021-03-02

They can hear well up to about forty years old, but then suddenly deafness strikes people with DFNA9. The cells of the inner ear can no longer reverse the damage caused by a genetic defect in their DNA. Researchers at Radboud university medical center have now developed a "genetic patch" for this type of hereditary deafness, with which they can eliminate the problems in the hearing cells. Further research in animals and humans is needed to bring the genetic patch to the clinic as a therapy.

Hereditary deafness can manifest itself in different ways. Often the hereditary defect (mutation) immediately causes deafness from birth. Sometimes, as with DFNA9, you experience the initial ...

2021-03-02

Philadelphia, March 2, 2021--Taking the first deep dive into how the immune system is behaving in patients with multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C), researchers at Children's Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP) and the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania have found that children with this condition have highly activated immune systems that, in many ways, are more similar to those of adults with severe COVID-19. The results, published today in Science Immunology, show that better understanding the immune activation in patients with MIS-C could not only help better treat those patients but also improve treatment for adults with ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Food for thought: New maps reveal how brains are kept nourished

Micro-scale depictions solve century-old puzzle of brain energy use and blood vessel clusters