(Press-News.org) Boulder, Colo., USA: Several articles were published online ahead of print

for GSA Bulletin in February. Topics include earthquake cycles in

southern Cascadia, fault dynamics in the Gulf of Mexico, debris flow after

wildfires, the assembly of Rodinia, and the case for no ring fracture in

Mono basin.

Jurassic evolution of the Qaidam Basin in western China: Constrained by

stratigraphic

succession, detrital zircon U-Pb geochronology and Hf isotope analysis

Tao Qian; Zongxiu Wang; Yu Wang; Shaofeng Liu; Wanli Gao ...

Abstract:

The formation and evolution of an intracontinental basin triggered via the

subduction or collision of plates at continental margins can record

intracontinental tectonic processes. As a typical intracontinental basin

during the Jurassic, the Qaidam Basin in western China records how this

extensional basin formed and evolved in response to distant subduction or

collisional processes and tectonism caused by stresses transmitted from

distant convergent plate margins. The Jurassic evolution of the Qaidam

Basin, in terms of basin-filling architecture, sediment dispersal pattern

and basin properties, remains speculative; hence, these uncertainties need

to be revisited. An integrated study of the stratigraphic succession,

conglomerates, U-Pb geochronology, and Hf isotopes of detrital zircons was

adopted to elucidate the Jurassic evolutionary process of the Qaidam Basin.

The results show that a discrete Jurassic terrestrial succession

characterized by alluvial fan, braided stream, braided river delta, and

lacustrine deposits developed on the western and northern margins of the

Qaidam Basin. The stratigraphic succession, U-Pb age dating, and Hf isotope

analysis, along with the reconstructed provenance results, suggest

small-scale distribution of Lower Jurassic sediments deposited via

autochthonous sedimentation on the western margin of the basin, with

material mainly originating from the Altyn Tagh Range. Lower Jurassic

sediments in the western segment of the northern basin were shed from the

Qilian Range (especially the South Qilian) and Eastern Kunlun Range. And

coeval sediments in the eastern segment of the northern basin were

originated from the Quanji massif. During the Middle-Late Jurassic, the

primary source areas were the Qilian Range and Eastern Kunlun Range, which

fed material to the whole basin. The Jurassic sedimentary environment in

the Qaidam Basin evolved from a series of small-scale, scattered, and

rift-related depressions distributed on the western and northern margins

during the Early Jurassic to a larger, extensive, and unified depression

occupying the whole basin in the Middle Jurassic. The Altyn Tagh Range rose

to a certain extent during the Early Jurassic but lacked large-scale

strike-slip tectonism throughout the Jurassic. At that time, the North

Qaidam tectonic belt had not yet been uplifted and did not shed material

into the basin during the Jurassic. The Qaidam Basin experienced

intracontinental extensional tectonism with a northeast-southwest trend

throughout the Jurassic in response to far-field effects driven by the

sequential northward or northeastward amalgamation of blocks to the

southern margin of the Qaidam Block and successive accretion of the

Qiangtang Block and Lhasa Block onto the southern Eurasian margin during

the Late Triassic−Early Jurassic and Late Jurassic−Early Cretaceous,

respectively.

View article: END

New GSA bulletin articles published ahead of print in February

2021-03-02

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

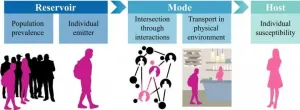

Indoors, outdoors, 6 feet apart? Transmission risk of airborne viruses can be quantified

2021-03-02

In the 1995 movie "Outbreak," Dustin Hoffman's character realizes, with appropriately dramatic horror, that an infectious virus is "airborne" because it's found to be spreading through hospital vents.

The issue of whether our real-life pandemic virus, SARS-CoV-2, is "airborne" is predictably more complex. The current body of evidence suggests that COVID-19 primarily spreads through respiratory droplets - the small, liquid particles you sneeze or cough, that travel some distance, and fall to the floor. But consensus is mounting that, under the right circumstances, smaller floating particles called aerosols can carry the virus over longer distances and remain ...

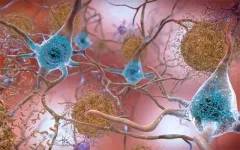

Novel drug prevents amyloid plaques, a hallmark of Alzheimer's disease

2021-03-02

Amyloid plaques are pathological hallmarks of Alzheimer's disease (AD) -- clumps of misfolded proteins that accumulate in the brain, disrupting and killing neurons and resulting in the progressive cognitive impairment that is characteristic of the widespread neurological disorder.

In a new study, published March 2, 2021 in the Journal of Experimental Medicine (JEM), researchers at University of California San Diego School of Medicine, Massachusetts General Hospital and elsewhere have identified a new drug that could prevent AD by modulating, rather than inhibiting, a key enzyme involved ...

A quantum internet is closer to reality, thanks to this switch

2021-03-02

WEST LAFAYETTE, Ind. -- When quantum computers become more powerful and widespread, they will need a robust quantum internet to communicate.

Purdue University engineers have addressed an issue barring the development of quantum networks that are big enough to reliably support more than a handful of users.

The method, demonstrated in a paper published in Optica, could help lay the groundwork for when a large number of quantum computers, quantum sensors and other quantum technology are ready to go online and communicate with each other.

The team deployed a programmable switch to adjust how much data goes to each ...

Scientists use forest color to gauge permafrost depth

2021-03-02

Scientists regularly use remote sensing drones and satellites to record how climate change affects permafrost thaw rates -- methods that work well in barren tundra landscapes where there's nothing to obstruct the view.

But in boreal regions, which harbor a significant portion of the world's permafrost, obscuring vegetation can stymy even the most advanced remote sensing technology.

In a study published in January, researchers in Germany and at the University of Alaska Fairbanks' Geophysical Institute developed a method of using satellite imagery to measure the depth of thaw directly above permafrost in boreal ecosystems. Rather than trying to peer past ...

A genetic patch to prevent hereditary deafness

2021-03-02

They can hear well up to about forty years old, but then suddenly deafness strikes people with DFNA9. The cells of the inner ear can no longer reverse the damage caused by a genetic defect in their DNA. Researchers at Radboud university medical center have now developed a "genetic patch" for this type of hereditary deafness, with which they can eliminate the problems in the hearing cells. Further research in animals and humans is needed to bring the genetic patch to the clinic as a therapy.

Hereditary deafness can manifest itself in different ways. Often the hereditary defect (mutation) immediately causes deafness from birth. Sometimes, as with DFNA9, you experience the initial ...

Deep immune profiling shows significant immune activation in children with MIS-C

2021-03-02

Philadelphia, March 2, 2021--Taking the first deep dive into how the immune system is behaving in patients with multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C), researchers at Children's Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP) and the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania have found that children with this condition have highly activated immune systems that, in many ways, are more similar to those of adults with severe COVID-19. The results, published today in Science Immunology, show that better understanding the immune activation in patients with MIS-C could not only help better treat those patients but also improve treatment for adults with ...

Study of severe pediatric COVID-19 syndrome highlights differences in immune responses to SARS-CoV-2

2021-03-02

A new study of patients with Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children (MIS-C), a rare but severe complication of COVID-19 in children, reveals distinct immune features of COVID-19 not seen in adults that may clue scientists in to why SARS-CoV-2 infection manifests differently in children compared with adults. Their results showed that although the immune landscape in pediatric COVID-19 was similar to that in adults, MIS-C patients uniquely exhibited increased activation of a blood vessel-patrolling CD8+ killer T cell subset, and all pediatric COVID-19 patients harbored greater B cell frequencies for a more prolonged period of time than observed in healthy adults. MIS-C is characterized by pervasive inflammation, an array of symptoms ranging from fever ...

An instructor's guide to reducing college students' stress and anxiety

2021-03-02

Orange, Calif. - Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, college students were reporting record levels of stress and anxiety. According to the American College Health Association END ...

Deepwater Horizon's long-lasting legacy for dolphins

2021-03-02

The Deepwater Horizon disaster began on April 20, 2010 with an explosion on a BP-operated oil drilling rig in the Gulf of Mexico that killed 11 workers. Almost immediately, oil began spilling into the waters of the gulf, an environmental calamity that took months to bring under control, but not before it became the largest oil spill in the history of the petroleum industry.

Nearly 10 years have passed since then, and the oil slick has long since dispersed. Yet, despite early predictions, area wildlife are still feeling the effects of that oil, and research published in Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry has shown that negative health impacts have befallen not only dolphins alive at the time of the spill, but also in their young, born years later.

A team of researchers, including ...

Yale team finds dozens of genes that block regeneration of neurons

2021-03-02

When central nervous system cells in the brain and spine are damaged by disease or injury, they fail to regenerate, limiting the body's ability to recover. In contrast, peripheral nerve cells that serve most other areas of the body are more able to regenerate. Scientists for decades have searched for molecular clues as to why axons -- the threadlike projections which allow communication between central nervous system cells -- cannot repair themselves after stroke, spinal cord damage, or traumatic brain injuries.

In a massive screen of 400 mouse genes, Yale School of Medicine ...