(Press-News.org) Induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSC) are suitable for discovering the genes that underly complex and also rare genetic diseases. Scientists from the German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ) and the European Molecular Biology Laboratory (EMBL), together with international partners, have studied genotype-phenotype relationships in iPSCs using data from approximately one thousand donors.

Tens of thousands of tiny genetic variations (SNPs, single nucleotide polymorphisms) have been identified in the human genome that are associated with specific diseases. Many of these genetic variants are not located in the protein-coding regions of genes, but affect regulatory sections. Therefore, scientists are trying to find out if and in which tissues these variants can be linked to changes in the activity of specific genes.

Typically, such analyses are performed in blood cells or tissue biopsies, depending on the type of disease. "Pluripotent stem cells, however, might be better suited for this purpose in many cases, as they are undifferentiated and therefore reflect the ancestral state of all cells," says Oliver Stegle, division head at the German Cancer Research Center and group leader at EMBL. "Stem cells could be particularly relevant when searching for the cause of diseases that occur early in development." Pluripotent stem cells can be generated in the culture dish from normal body cells obtained from a blood sample, for example. They are referred to as "induced pluripotent stem cells," or iPSCs for short, since they are not naturally occurring stem cells.

Together with scientists from Stanford University and additional international cooperation partners, Oliver Stegle's team has compiled sequence and transcriptome data on iPSCs from around 1000 donors. The researchers systematically examined these data to identify correlations between individual genetic variants and altered expression patterns in stem cells. The results have now been published in the journal Nature Genetics.

For more than 67 percent of all genes active in iPSCs, the researchers found differential expression patterns depending on genetic variants. Many of these associations are novel and have not been described in somatic cell types before. For over 4000 of these associations, the genetic variants responsible for the altered expression patterns could be linked to specific diseases. These included, for example, variants associated with coronary heart disease, lipid metabolism disorders or hereditary cancers.

Stegle and colleagues also investigated whether iPS are suitable for identifying the causative genes of rare genetic diseases. They used iPSC lines from 65 patients who suffered from various rare diseases, whose causal gene defects were already known through previous analyses. In the transcriptome data of these iPSC lines, the scientists searched for particularly conspicuous "outliers" in the expression pattern. These analyses reliably led to the trace of the genetic basis of the disease. "Such screenings were previously impossible because there were simply no sufficiently large reference collections of iPS transcriptomes," explained Marc Jan Bonder, first author of the study.

"We were surprised to find such a large number of disease-associated genetic variants that are already visible in the expression pattern at the earliest time point of cell differentiation, represented by the iPSCs". Until now, the relevance of iPSCs for such biomedical analyses has been significantly underestimated.

In a companion paper, published in the same issue of Nature Genetics, Stegle and colleagues from EMBL-EBI and the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute used more than 200 iPSC lines to investigate how genetic variants affect differentiation into neuronal cells.

The scientists performed RNA single-cell sequencing at different time points of neuronal cell differentiation. This allowed them to analyze how genetic variants affect expression patterns in different cellular states, including different neuronal cell types. "The study demonstrates the power of combining single-cell sequencing with iPSC technologies to dissect the effect of genetic variants in cell types that would otherwise be inaccessible," Stegle explains.

INFORMATION:

Bonder, M.J. Smail, C., Gloudemans, M.J., Frésard, L., Jakubosky, D., D'Antonio, M., Li, X., Ferraro, N.M., Carcamo-Orive, I., Mirauta, B., Seaton, D.D., Cai, N., Kilpinen, H., Vakili, D., Horta, D., Wheeler, M.T., Zhao, C., Zastrow, D.B., Bonner, D.E., HipSci Consortium, iPSCORE Consortium, GENESiPS Consortium, PhLiPS Consortium, Undiagnosed Diseases Network, Knowles, J.W., Smith, E.N., Frazer, K.A., Montgomery, S.B., Stegle, O.: Identification of rare and common disease variants using population-scale transcriptomics of pluripotent cells.

Nature Genetics 2021, DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.1038/s41588-021-00800-7

Jerber, J., Seaton, D.D., Cuomo, A.S.E., Kumasaka, N., Haldane, J., Steer, J., Patel, M., Pearce, D., Andersson, M., Bonder, M.J., Mountjoy, E., Ghoussaini, M., Lancaster, M.A., HipSci Consortium, Marioni, J.C., Merkle, F.T., Gaffney, D.J., Stegle, O: Population-scale single-cell RNA-seq profiling across dopaminergic neuron differentiation

Nature Genetics 2021, DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.1038/s41588-021-00801-6

The German Cancer Research Center (Deutsches Krebsforschungszentrum, DKFZ) with its more than 3,000 employees is the largest biomedical research institution in Germany. More than 1,300 scientists at the DKFZ investigate how cancer develops, identify cancer risk factors and search for new strategies to prevent people from developing cancer. They are developing new methods to diagnose tumors more precisely and treat cancer patients more successfully. The DKFZ's Cancer Information Service (KID) provides patients, interested citizens and experts with individual answers to all questions on cancer.

Jointly with partners from the university hospitals, the DKFZ operates the National Center for Tumor Diseases (NCT) in Heidelberg and Dresden, and the Hopp Children's Tumor Center KiTZ in Heidelberg. In the German Consortium for Translational Cancer Research (DKTK), one of the six German Centers for Health Research, the DKFZ maintains translational centers at seven university partner locations. NCT and DKTK sites combine excellent university medicine with the high-profile research of the DKFZ. They contribute to the endeavor of transferring promising approaches from cancer research to the clinic and thus improving the chances of cancer patients.

The DKFZ is 90 percent financed by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research and 10 percent by the state of Baden-Württemberg. The DKFZ is a member of the Helmholtz Association of German Research Centers.

A team of scientists from the University of Cologne (Germany) and the University of Uppsala (Sweden) has created a model that can describe and predict the evolution of antibiotic resistance in bacteria. Resistance to antibiotics evolves through a variety of mechanisms. A central and still unresolved question is how resistance evolution affects cell growth at different drug concentrations. The new model predicts growth rates and resistance levels of common resistant bacterial mutants at different drug doses. These predictions are confirmed by empirical growth inhibition curves and genomic data from Escherichia coli populations. ...

Over evolutionary time scales, a single gene may acquire different roles in diverging species. However, revealing the multiple hidden roles of a gene was not possible before genome editing came along. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL) Professor and HHMI Investigator Zach Lippman and CSHL postdoctoral fellow Anat Hendelman collaborated with Idan Efroni, HHMI International Investigator at Hebrew University Faculty of Agriculture in Israel, to uncover this mystery. They dissected the activity of a developmental gene, WOX9, in different plants and at different moments in development. Using genome editing, they found that without changing the protein produced by the gene, they ...

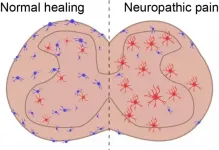

CHAPEL HILL, NC - One of the hallmarks of chronic pain is inflammation, and scientists at the UNC School of Medicine have discovered that anti-inflammatory cells called MRC1+ macrophages are dysfunctional in an animal model of neuropathic pain. Returning these cells to their normal state could offer a route to treating debilitating pain caused by nerve damage or a malfunctioning nervous system.

The researchers, who published their work in Neuron, found that stimulating the expression of an anti-inflammatory protein called CD163 reduced signs of neuroinflammation in the spinal cord of mice with neuropathic pain.

"Macrophages are a type of immune cell that are found in the blood and in tissues ...

What The Study Did: In this study of return-to-play cardiac testing performed on 789 professional athletes with COVID-19 infection, imaging evidence of inflammatory heart disease that resulted in restriction from play was identified in five athletes (0.6%). No adverse cardiac events occurred in the athletes who underwent cardiac screening and resumed professional sports participation.

Authors: David J. Engel, M.D., of Columbia University Irving Medical Center in New York, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamacardio.2021.0565)

Editor's Note: The article includes conflict of ...

What The Study Did: Using reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction testing, this study found that SARS-CoV-2 was present on the ocular surface in 52 of 91 patients with COVID-19 (57.1%). The virus may also be detected on ocular surfaces in patients with COVID-19 when the nasopharyngeal swab is negative.

Authors: Claudio Azzolini, M.D., of the University of Insubria in Varese, Italy, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2020.5464)

Editor's ...

What The Study Did: This study of more than 526,000 procedures across 17 institutions reports a significant decrease in the use of lasers and cryotherapy, retinal detachment repairs and other vitrectomies, beginning mid-March last year and lasting at least until May.

Authors: Mark P. Breazzano, M.D., of the Wilmer Eye Institute at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2021.0036)

Editor's Note: The article includes conflict of interest and funding/support disclosures. ...

What The Study Did: Clinical trial registrations for COVID-19 interventions that were highly publicized during the COVID-19 pandemic compared with treatments not comparably promoted were assessed in this study.

Authors: Nadir Yehya, M.D., M.S.C.E., of the Children's Hospital of Philadelphia, is the author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.0689)

Editor's Note: The article includes conflicts of interest and funding/support disclosures. ...

What The Study Did: Researchers evaluated the feasibility and acceptability of using a mobile robotic system to perform health care tasks such as acquiring vital signs, obtaining nasal or oral swabs and facilitating contactless triage interviews of patients with potential COVID-19 in the emergency department.

Authors: Giovanni Traverso M.B., B.Chir., Ph.D., of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge, Massachusetts, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.0667)

Editor's Note: The article includes conflicts ...

CAMBRIDGE, MA -- In the era of social distancing, using robots for some health care interactions is a promising way to reduce in-person contact between health care workers and sick patients. However, a key question that needs to be answered is how patients will react to a robot entering the exam room.

Researchers from MIT and Brigham and Women's Hospital recently set out to answer that question. In a study performed in the emergency department at Brigham and Women's, the team found that a large majority of patients reported that interacting with a health care provider via a video screen mounted on a robot was similar to an in-person interaction with a health care worker.

"We're ...

How governments and companies should listen to the people on climate change

People are more engaged in reducing carbon emissions than previously thought - and governments, scientists and companies should listen to them - according to new research from the University of East Anglia and the UK Energy Research Centre.

A new study published today in Nature Energyy investigates how invested people are in making the changes needed to reduce carbon emissions and stop climate change.

The study shows that people, their views and actions should be included more when it comes to how we transform the way we use energy, to keep global average temperatures well below 2°C as set out in the Paris COP21 climate agreement.

Lead ...