(Press-News.org) To succeed in mating, many male frogs sit in one place and call to their potential mates. But this raises an important question familiar to anyone trying to listen to someone talking at a busy cocktail party: how does a female hear and then find a choice male of her own species among all the irrelevant background noise, including the sound of other frog species? Now, researchers reporting March 4 in the journal Current Biology have found that they do it thanks to a set of lungs that, when inflated, reduce their eardrum's sensitivity to environmental noise in a specific frequency range, making it easier to zero in on the calls of their mates.

"In essence, the lungs cancel the eardrum's response to noise, particularly some of the noise encountered in a cacophonous breeding 'chorus,' where the males of multiple other species also call simultaneously," says lead author Norman Lee of St. Olaf College in Minnesota.

The researchers explain that what their lungs are doing is called "spectral contrast enhancement." That's because it makes the frequencies in the spectrum of a male's call stand out relative to noise at adjacent frequencies.

"This is analogous to signal-processing algorithms for spectral contrast enhancement implemented in some hearing aids and cochlear implants," says senior author Mark Bee of the University of Minnesota-Twin Cities. "In humans, these algorithms are designed to amplify or 'boost' the frequencies present in speech sounds, attenuate or 'filter out' frequencies present between those in speech sounds, or both. In frogs, the lungs appear to attenuate frequencies occurring between those present in male mating calls. We believe the physical mechanism by which this occurs is similar in principle to how noise-canceling headphones work."

It's long been known to scientists that vocal signals are key to reproduction in most frogs. In fact, frogs possess a unique sound pathway that can transmit sounds from their air-filled lungs to their air-filled middle ears through the glottis, mouth cavity, and Eustachian tubes. But the precise function of this lung-to-ear sound transmission pathway had been a puzzle. Earlier studies suggested that the frog's lungs might play a role in increasing the degree to which eardrum vibrations were direction dependent, thereby improving the ability of listeners to locate a sexually advertising male. But Bee's team has found that wasn't the case.

Further analysis of the data suggested a different explanation: while the state of the lungs' inflation had no effect on directional hearing, there was a substantial impact on the sensitivity of the eardrum. With inflated lungs, the eardrum vibrated less in response to sounds in a specific frequency range. It led them to a new idea: that the lungs were dampening vibrations, thereby canceling out noise.

Indeed, their studies using laser vibrometry showed that the resonance of inflated lungs selectively reduces the eardrum's sensitivity to frequencies between the two spectral

peaks present in the mating calls of frogs of the same species. It confirmed that a female can hear males of her own species no matter the state of her lungs' inflation. So, the lungs had no impact on the "signals" of interest to a female. But what about the "noise"?

They already knew that a major source of noise for any given species of frog is the calls of other frog species breeding at the same time and calling in the same choruses. But they had no idea how many or which other species might "co-call" in a mixed species chorus with green treefrogs across its geographic range, much less how the frequency spectrum of their calls looked. To find out, they turned to publicly available data from a citizen science project called the North American Amphibian Monitoring Program. Their analysis of those data suggests that the green treefrog's inflated lungs would make it harder to hear the calls of other species while leaving their ability to hear the calls of their own species intact.

"Needless to say, we think this result--a frog's lungs canceling the eardrum's response to noise created by other species of frogs--is pretty cool!" Bee says.

Finally, they created a physiological model of sound processing by the green treefrog's inner ear to examine how the lung's impact on the eardrum might be converted into more robust neural responses to the calls of their own species. They think it works like this: the inner ear is, in some ways, "tuned" to respond best to the frequencies in the species' own calls. But that tuning is not perfect. The authors suggest that a primary function of the lungs in hearing is to sharpen or improve this tuning, allowing the inner ear to generate relatively stronger neural responses to the species' own calls by reducing the neural responses driven by the calls of other species.

The findings demonstrate the power of evolution to co-opt pre-existing adaptations for new functions, the researchers say. In future work, they want to find out more about the physical interaction between the three sources of sound (external, internal via the opposite ear, and internal via the lungs) that determine the eardrum's vibration response. They also want to know more about how widespread noise cancellation is in frogs.

INFORMATION:

This work was supported by the U.S. National Science Foundation.

Current Biology, Lee et al.: "Lung Mediated Auditory Contrast Enhancement Improves the Signal-to-Noise Ratio for Communication in Frogs"

https://www.cell.com/current-biology/fulltext/S0960-9822(21)00113-5

Current Biology (@CurrentBiology), published by Cell Press, is a bimonthly journal that features papers across all areas of biology. Current Biology strives to foster communication across fields of biology, both by publishing important findings of general interest and through highly accessible front matter for non-specialists. Visit http://www.cell.com/current-biology. To receive Cell Press media alerts, contact press@cell.com.

Brain cells called astrocytes derived from the induced pluripotent stem cells of patients with bipolar disorder offer suboptimal support for neuronal activity. In a paper appearing March 4th in the journal Stem Cell Reports, researchers show that this malfunction can be traced to an inflammation-promoting molecule called interleukin-6 (IL-6), which is secreted by astrocytes. The results highlight the potential role of astrocyte-mediated inflammatory signaling in the psychiatric disease, although further investigation is needed.

"Our findings suggest that IL-6 may contribute to defects associated with bipolar disorder, opening new avenues for clinical intervention," says co-senior study author Fred Gage ...

New collaborative research from Northwestern University and Lund University may have people heading to their backyard instead of the store at the outset of this year's mosquito season.

Often used as an additive for cat toys and treats due to its euphoric and hallucinogenic effects on cats, catnip has also long been known for its powerful repellent action on insects, mosquitoes in particular. Recent research shows catnip compounds to be at least as effective as synthetic insect repellents such as DEET.

But until now, the mechanism that triggered insects' aversion to this common member of the mint family was unknown. In a paper ...

Existing gene drive technologies could be combined to help control the invasive grey squirrel population in the UK with little risk to other populations, according to a modelling study published in Scientific Reports.

Gene drives introduce genes into a population that have been changed to induce infertility in females, allowing for the control of population size. However, they face technical challenges, such as controlling the spread of altered genes as gene drive individuals mate with wild individuals, and the development of genetic resistance, which may render the gene drive ineffective.

To address these challenges, Nicky Faber and colleagues used computer modelling to investigate the effectiveness of a combination of three gene ...

Using theoretical models of bacterial metabolism and reproduction, scientists can predict the type of resistance that bacteria will develop when they are exposed to antibiotics. This has now been shown by an Uppsala University research team, in collaboration with colleagues in Cologne, Germany. The study is published in the journal Nature Ecology and Evolution.

In medical and pharmaceutical research, there is keen interest in finding the answer to how fast, and through which mechanisms, bacteria develop antibiotic resistance. Another goal is to understand how this resistance, in turn, affects bacterial growth and pathogenicity.

"This kind of knowledge would enable better tracking and slowing ...

Induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSC) are suitable for discovering the genes that underly complex and also rare genetic diseases. Scientists from the German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ) and the European Molecular Biology Laboratory (EMBL), together with international partners, have studied genotype-phenotype relationships in iPSCs using data from approximately one thousand donors.

Tens of thousands of tiny genetic variations (SNPs, single nucleotide polymorphisms) have been identified in the human genome that are associated with specific diseases. Many of these genetic variants are ...

A team of scientists from the University of Cologne (Germany) and the University of Uppsala (Sweden) has created a model that can describe and predict the evolution of antibiotic resistance in bacteria. Resistance to antibiotics evolves through a variety of mechanisms. A central and still unresolved question is how resistance evolution affects cell growth at different drug concentrations. The new model predicts growth rates and resistance levels of common resistant bacterial mutants at different drug doses. These predictions are confirmed by empirical growth inhibition curves and genomic data from Escherichia coli populations. ...

Over evolutionary time scales, a single gene may acquire different roles in diverging species. However, revealing the multiple hidden roles of a gene was not possible before genome editing came along. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL) Professor and HHMI Investigator Zach Lippman and CSHL postdoctoral fellow Anat Hendelman collaborated with Idan Efroni, HHMI International Investigator at Hebrew University Faculty of Agriculture in Israel, to uncover this mystery. They dissected the activity of a developmental gene, WOX9, in different plants and at different moments in development. Using genome editing, they found that without changing the protein produced by the gene, they ...

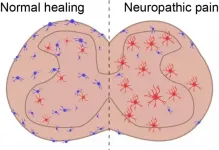

CHAPEL HILL, NC - One of the hallmarks of chronic pain is inflammation, and scientists at the UNC School of Medicine have discovered that anti-inflammatory cells called MRC1+ macrophages are dysfunctional in an animal model of neuropathic pain. Returning these cells to their normal state could offer a route to treating debilitating pain caused by nerve damage or a malfunctioning nervous system.

The researchers, who published their work in Neuron, found that stimulating the expression of an anti-inflammatory protein called CD163 reduced signs of neuroinflammation in the spinal cord of mice with neuropathic pain.

"Macrophages are a type of immune cell that are found in the blood and in tissues ...

What The Study Did: In this study of return-to-play cardiac testing performed on 789 professional athletes with COVID-19 infection, imaging evidence of inflammatory heart disease that resulted in restriction from play was identified in five athletes (0.6%). No adverse cardiac events occurred in the athletes who underwent cardiac screening and resumed professional sports participation.

Authors: David J. Engel, M.D., of Columbia University Irving Medical Center in New York, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamacardio.2021.0565)

Editor's Note: The article includes conflict of ...

What The Study Did: Using reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction testing, this study found that SARS-CoV-2 was present on the ocular surface in 52 of 91 patients with COVID-19 (57.1%). The virus may also be detected on ocular surfaces in patients with COVID-19 when the nasopharyngeal swab is negative.

Authors: Claudio Azzolini, M.D., of the University of Insubria in Varese, Italy, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2020.5464)

Editor's ...